At the risk of stating the incredibly obvious, the violin is hard to play. Some players find that, in order to master a specific skill, it’s useful to strip it from a wider musical context and focus on the specific skill itself, in isolation. That’s where violin etudes come in.

Today we’re looking at five of the most loved – or loathed, depending on your perspective – sets of etudes that violinists use today, in escalating order of difficulty.

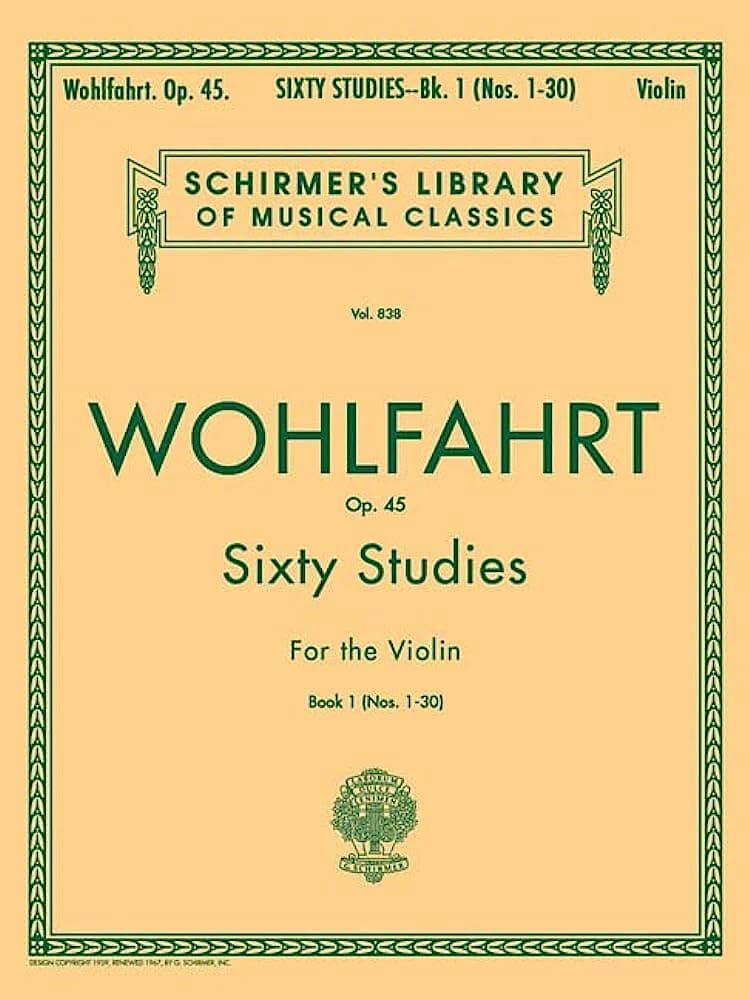

Wohlfahrt: 60 Studies Op. 45

Franz Wohlfahrt was a violinist who lived from 1833 to 1884 in Leipzig. Fun fact: he studied with Ferdinand David, who was Mendelssohn’s friend and the violinist for whom the Mendelssohn violin concerto was written!

© Amazon

So with that kind of pedigree, it makes sense that these etudes are actually, as far as etudes go, very elegant and enjoyable. They’re a great resource for a violinist after you’ve mastered first position and are working on basic intonation and efficient string crossings. The first etude, a gentle perpetual motion, is especially famous for its bowing variations to aid in proper bow distribution.

Otakar Ševčík: School of Violin Technics

Schradieck: School of Violin Technique

I’m putting the Ševčík and Schradieck etudes together because they complement each other and have a reputation of being…well, soulless. Effective, maybe, but soulless, and incredibly repetitive to boot. Nevertheless, most violinists will probably run across them over the course of their studies, so they’re good to be aware of and to browse through. Besides, Otakar Ševčík taught some of the best violinists of his generation, including Kubelík, Morini, and Zimbalist, so he must have known what he was doing! Just don’t spend hours a day on these or you’ll injure yourself (no joke!).

© dearviolinstudents.com

Here’s a tip for you: when I started playing viola, I learned alto clef within a week or so by drilling the first couple pages of the viola transcription of Schradieck’s School of Violin Technique. Speaking more broadly, they’d also be great for a beginner violinist looking to cement their treble clef-reading ability.

Mazas: Etudes, Op. 36

Jacques Mazas was born in 1782 and died in 1849, and in addition to being a violinist, was also a composer and conductor.

© nakas.com.cy

This is one of the etude books I never got around to using or studying, but I’ve always heard great things about it. It’s one of the main bridge resources to get a player between Wohlfahrt and Kreutzer. Apparently, these etudes feel more like “real” pieces than many other etudes do, and glancing through the book now, I can see why. The first focuses on crescendo and decrescendo; the second, bow distribution (a prime skill for etudes to help with); the third, bow control in the upper half of the bow; etc. But the etudes, while featuring patterns useful for technical work, are not monotonous, and include variety and room to explore color and expression. Recommended!

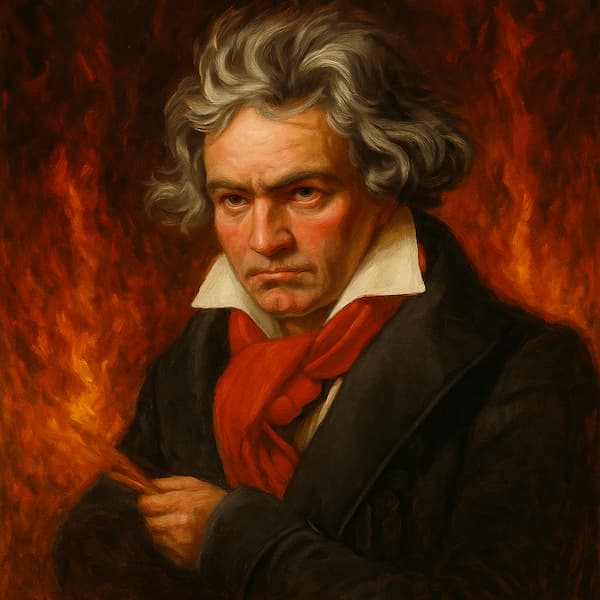

Kreutzer: 42 Etudes

In case you’re wondering, yes, the Kreutzer Etudes were written by the same guy who Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata is named after: violinist Rudolfe Kreutzer, teacher, performer, and composer of operas (he wrote forty!).

© woodbrass.com

The Kreutzer etudes were composed around 1796 and are sometimes referred to as the violinists’ Bible. Their cleverness and adaptability have kept them in service for over two centuries. I think every violinist has played the first etude – a study in many things, including very slow bowing and bow distribution – before they were ready, and run out of bow in a very comical way! But practice that first etude every day, bringing down the metronome tick every few days, and you’ll soon hear your tone and bow control start to improve. The second, perpetual motion, is also very useful for studying bowing patterns, and overall just a classic.

Be forewarned: you’ll have to be a late intermediate to early advanced player to take full advantage of these etudes.

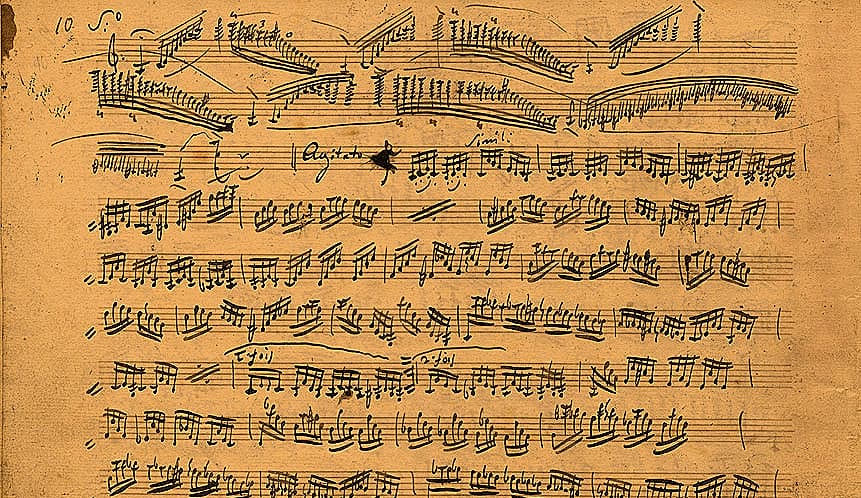

Paganini: 24 Caprices

Paganini’s Caprices are the culmination of years of etudes, scales, and technical studies…and they’re too difficult for most violinists to play. They are 24 of the craziest pieces ever written for our instrument, exploring endless, nightmarish technical challenges, from ricochet bowing to double-stopped trills and thirds. They’re also so musical that violinists record complete sets for listeners to enjoy!

© Classical Register

Don’t set off on learning these too early: they’re tempting, but they’re so demanding, they might injure you if you don’t know exactly what you’re doing. According to historians, Paganini himself probably had hypermobile joints, enabling him to play things that others can’t. Instead, cue up a recording of your favorite violinist playing them, because many have taken up the challenge of learning and recording them all. And keep practicing. With time and persistence, you’ll be able to attack them, too!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter