‘It’s Exciting, It’s Stressful… Hopefully You Will Find Your Own Way’

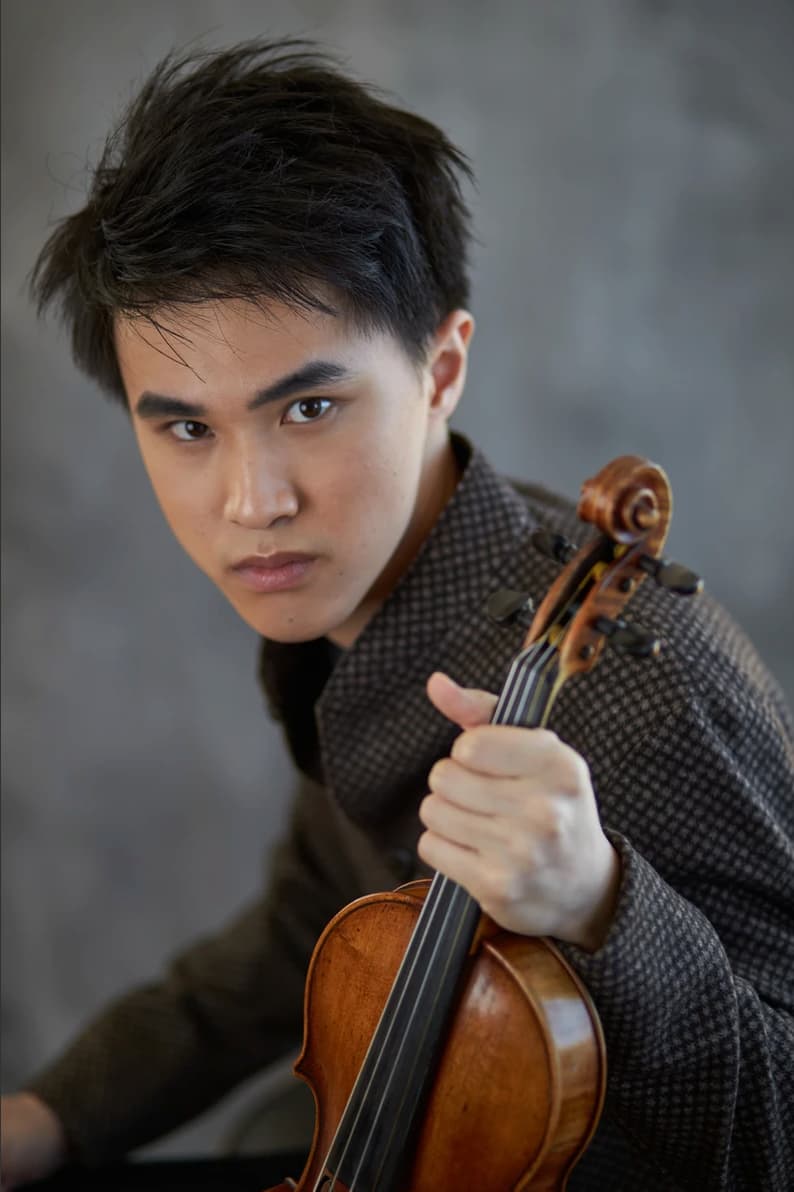

Kevin Zhu © Fred R. Conrad

Young violinist Kevin Zhu is making a reputation as a sought-after artist, earning praise for his ‘awesome technical command and maturity’ (The Strad). He has toured across the US and Europe, performing with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Moscow Virtuosi, and China Philharmonic Orchestra and collaborating with musicians including Itzhak Perlman, Lawrence Power, and Jan Vogler.

Originally from Cupertino, a laid-back suburban Californian town, Kevin moved to New York aged 14 to study at Juilliard’s pre-college programme, and later full-time as an undergraduate. His time spent studying in New York with Li Lin and Itzhak Perlman, as well as at Itzhak Perlman’s summer school, left a lasting impression on him, helping to shape Kevin into a musician not only of technical virtuosity but of incredible thoughtfulness and sensitivity.

Kevin Zhu Plays Bartók’s Sonata for solo violin – I. Tempo di ciaccona

His own ‘musings’, published on his website, document aspects of his life on the road, as well as general impressions and reflections of life, music, and everything in between – topics ranging from how teaching changes one’s perspective to where to find the best Schnitzel in Munich.

Already with considerable success under his belt despite having just finished his studies, he tells me about what his move to New York meant to him, his recent forays into teaching, and the feeling of a new world of opportunities opening up.

How was it to move from California to New York?

When I got to New York I didn’t realise how loud it was, and how energetic the people were, how fast they walked and talked. It was like there was something vibrating in the air. It’s a crazy city. It has so much energy and vibrancy.

It was totally overwhelming for the first few weeks I was there but then I totally got used to it, and now I consider it my home.

How did you begin the violin?

Nobody else in my family does music as a profession. My father was the one who introduced music to me. He learned the violin when he was growing up in China during the Cultural Revolution.

He loved the violin, but never considered himself good enough to do it as a profession. He always kept up this inner love for music and the violin, and when I was very young he would play some Chinese folk songs in the living room. I was maybe two and a half or three years old, and I would sit there and listen for hours and hours. I think at that point my parents knew there was something very deeply wrong with their child!

All kidding aside, they sensed this kind of need or obsession with this magical thing, and so they got me a little plastic violin toy. It didn’t actually ‘work’ or make any sound, but it was just something a little toddler can carry around. I would carry it all around the house, to the kitchen, to the bathroom, to go to sleep – everything. I couldn’t let go of it. Soon afterwards they released I really liked it, so they got me a little baby violin.

In a funny turn of events, my first ‘teacher’ was an instructional DVD sent over from China. I don’t remember any of this consciously, but I’ve seen camcorder videos of this: my parents would put this instructional video on the TV and I would just try to imitate what I was seeing on the TV, and that was how I learned the violin for the first year! (After that I studied with a real teacher.)

Did you always know you wanted to be a violinist?

© Bruno Murialdo

It was for me a very natural part of my life. I never had the thought of putting much energy into anything else than the violin. It was always a little odd: in elementary school, after school kids would go play in the playground, play sports, basketball, do other extracurriculars, and what I did, because I wanted to and because I loved it, was I went home and played the violin.

I don’t know where it came from, but it just felt like I loved it so much.

What were your defining moments in New York?

I attended the Juilliard pre-college programme each Saturday – you go to this place, this haven for young kids who love music, so in a way it was very eye-opening that it was possible to be around other kids who loved music just as much as you.

Growing up in a suburban town in California, there might be one other person in the school who plays the piano or something.

And so once you enter this pre-college, surrounded by kids that love it as much as you do, you realise something, you think, ‘Wow, there’s a real community here.’ You can have friends who share the exact same passions as you, and that was very special for me.

The other really defining moment was when I attended the summer programmes. For six consecutive summers, I went to the Perlman music programme. Itzhak Perlman has a seven-week-long summer camp for kids between the ages of 12 and 18, only for string players.

I first went there when I was twelve, and that very quickly became a safe haven for me. I’d found something that I enjoyed so much, and that helped me when I went to the pre-college. I knew some people at pre-college from the summer programme, so it was like a reunion.

You find out very quickly that it’s a small world, but there are also lots of people that you don’t know! It’s a weird paradox, that you can become so close with some people and then realise when you go to college, the world opens up, and the same when you graduate college: the world opens up.

It must feel quite exciting to be at that point where the world is opening up.

It’s exciting, it’s stressful, it’s all good things and bad things combined, but that’s really what life is. Hopefully you find your own way.

Violinist Kevin Zhu | Wieniawski | Fantasia from Themes of Faust | Violin Channel Vanguard Concerts

Does writing your ‘musings’ help with your playing?

I felt like it was a way to get thoughts out and formalise ideas through a different channel. I’ve always found it interesting to track the line of logic. Very often in school, we had to write papers about art, history, music theory, analysing a piece or painting, comparing and contrasting two novels… and so I was always interested in following how an argument shaped up.

And then after that phase, I thought, ‘How can I keep writing but do it in a different way? How can I make a picture of something, how can I tell a story?’ And so it changed from this very logical, very methodical way into trying to channel some other emotion or feeling or experience through these words.

I certainly will not say that I am not a professional, but I like doing it.

You started teaching recently. How does it feel to be on the other side?

It feels like suddenly a lot of things become clear and then many things become much more unclear! You realise what you prioritise and what you value in a performance, and essentially when somebody plays for you, when you teach them, they’re giving you a performance of some kind, whether it’s something they’re fully comfortable with, whether it’s a work in progress, or whether they’re just starting.

And then you have to go into their learning process and guide them through it. I don’t want to impose my ideas or my playing style on the student, because I don’t think that’s as helpful as maybe helping to put one spark or idea in their head and let it marinate in their brain – then they take it themselves and make of it what they will.

So it’s interesting for me, as I start teaching, to become more aware of my priorities, but then also you realise how much effort and work my own teachers put into me, all these little pathways they would try to find to help bring me to a different place, to a different level.

That’s another world that’s opened up: this weird play of psychology, of how a person understands your words, how they understand the music, and how these two things are wrapped.

Eventually, you realise that because everybody is so different, everybody processes music and how you talk so differently, that you should be wary of being too self-indulgent, in a way.

Once again, you don’t want to just impose your ideas and say ‘I’m this other being, and you should just believe everything I say’. It’s more than you suggest things that you think might help them, and maybe they will take it in. There’s always this interplay, it’s a curious thing.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter