Playground without a bully, or plane without a pilot? Depending on the situation, eliminating one element of the equation can bring either joy or disaster. Where do conductors sit along this spectrum? While many orchestral musicians joke about the ineptitude of certain conductors, the rise in popularity of soloists directing their own concertos, with no conductor in sight, may have some ensemble members eating their words.

One could argue that eliminating the person on the podium brings a more direct contact between the musicians, and therefore the music. The lines of communication are freed up, and musical oneness and special connections can flourish, leading to fresher, more honest interpretations and a playing style liberated from the shackles of the oppressive timekeeper.

Daniel Barenboim conducts the Staatskapelle Berlin in Prom 69 at the Royal Albert Hall, London © Chris Christodoulou/BBC

Or are things really that simple? (Spoiler alert: of course not.)

It takes more than a little practice to be a good conductor, and while the soloist may have brilliant musical ideas, it’s all in how they communicate them to the ensemble they’re working with.

The notion of directing from the solo chair is nothing new; in fact, it actually predates the role of the conductor. Conductors only showed up regularly when, around the turn of the 19th century, music started to become complex enough to necessitate a separate person to be in charge of keeping everything together.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that every piece written in the era of conductors needs one. Many players still direct modern concertos from their instrument – at the end of the day, it mainly depends on the overall complexity of the piece, and the rehearsal time available.

Take clarinet concertos, for example. It’s not uncommon for a soloist to play Mozart or Copland concertos unconducted. However, they’re both quite different experiences for both soloist and orchestra.

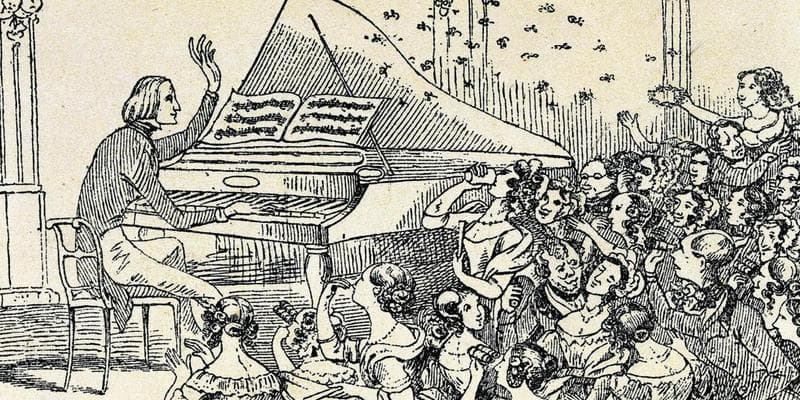

Theodor Hosemann’s 1846 caricature of Franz Liszt conducting at the piano (Public Domain)

The Copland features many more tempo changes and is more rhythmically complex, meaning the soloist would have to take a more active ‘conductor’ role in certain moments. The Mozart, with its unchanging time signatures and steady pulse throughout, is technically an easier piece to facilitate without a separate conductor.

This doesn’t mean, however, that the Mozart is easy to do without a conductor. The piece still has scope for a myriad of musical ideas and interpretations, and it takes a strong leader to communicate these to the ensemble.

While there are some notable exceptions – such as Barbara Hannigan conducting Ligeti’s wild Mysteries of the Macabre while also performing the unbelievably gymnastic solo line – it is more common to find ‘player-directors’ in classical concertos, where their brain space isn’t too occupied by the sheer logistics of actually conducting the music.

Ligeti: Mysteries of the Macabre Hannigan GSO

Anecdotally, I’ve heard mixed reviews from friends and colleagues about the success of player-directors. Some claim the best concerto performances they’ve ever seen have been conductorless, while others simply think it detracts from the soloist being able to do what they do best: be a soloist.

I’ve sat through concerts (both on stage and in the audience) where it seems like the ensemble was actually being dulled by the presence of the soloist. Shouldering the responsibility of leading an orchestra while also performing incredibly taxing solo parts can be a dangerous cocktail, sometimes leading to electrifying experiences, sometimes missing the mark.

While the presence of a conductor can go some way to alleviating these logistical problems, it’s by no means a guarantee. A concerto is a delicate interplay between conductor, soloist, and ensemble, each bringing their own personalities, preferences, likes and dislikes to the table.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard conducting at the piano © Hiroyuki Ito for The New York Times

So, should concertos be led from the instrument, or the baton? Of course, it depends on the specific person and repertoire in question, but there is no clear-cut answer. Taking away the conductor gives a much stronger sense of chamber music, but at what other cost? If the soloist doesn’t bring something else to the table, the attention of the players can be consumed by simply staying together rather than making music.

It’s the same in the debate about performing from memory: some argue the removal of the music stand is the removal of a barrier between performer and audience; others argue that the ensuing tightrope walk is an unnecessary extra burden to place on the performer, using up energy that takes them out of the musical moment.

Whether you love it or hate it, it looks like conductorless concertos aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. There have been successes and failures with and without stick-waving, and that’s the way it will probably continue for a long time to come.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter