Haydn was rich, but he wasn’t born wealthy…

He did come from humble origins, but for his gentrified English audience Joseph Haydn was an accomplished composer, businessman, and gentleman. Yet, his early years of poverty and struggles during his years as a freelancer musician made him astute and merciless in his business dealings. The noted Haydn Scholar James Webster writes, “Haydn always attempted to maximize his income, whether by negotiating the right to sell his music outside the Esterházy court, driving hard bargains with publishers or selling his works three and four times over to publishers in different countries.”

Joseph Haydn by Jean Urbain Guerin

In fact, a good many of Haydn’s business practices might nowadays be regarded as plain fraud, and they even surprised and shocked a good number of Haydn’s contemporaries. With copyright in its infancy, however, Haydn’s business model of exploiting multiple markets became a prototype for the next two generations of composers. Beethoven certainly learned his lessons well—including emotional outbursts and bristling demeanor—as did Mendelssohn and Chopin. And Haydn certainly knew how to market his goods. He described his Symphonies Nos. 76-78 as “beautiful, impressive and above all not very long symphonies…and in particular everything very easy.”

Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 77 in B-flat Major (See Siang Wong, piano; Winterthur Musikkollegium)

How did Haydn become rich?

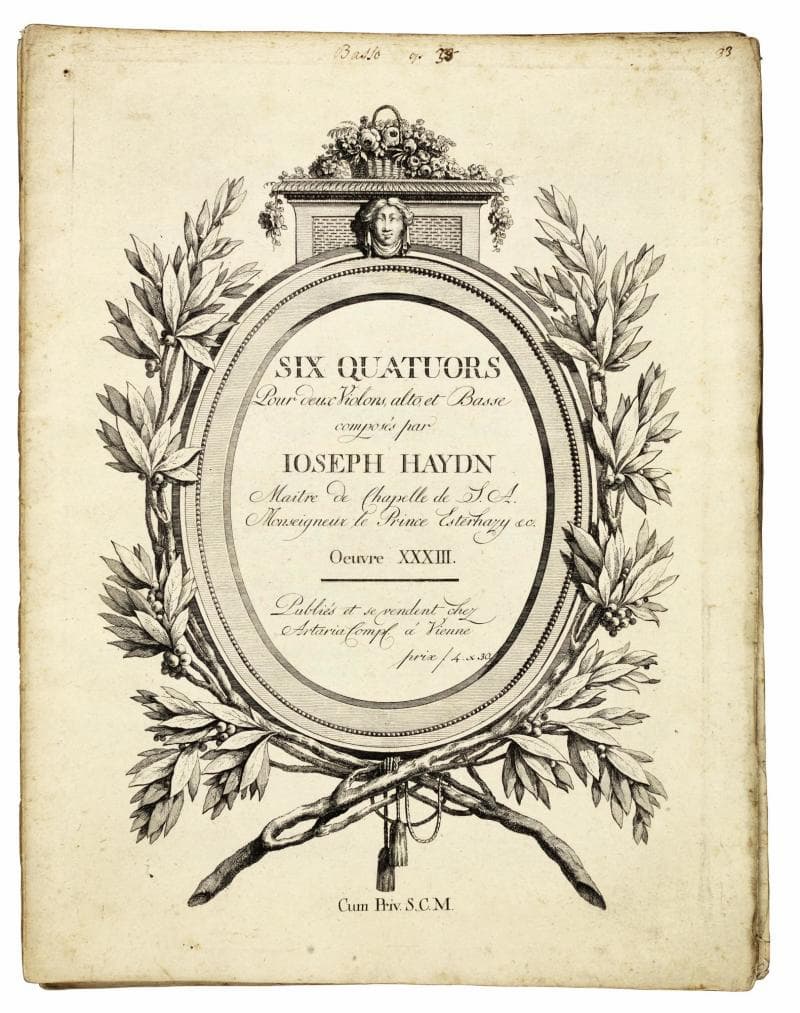

Haydn’s String Quartets Op. 33

Haydn’s quickly caught on to the fact that he could be selling a work in several countries, and therefore was able to receive multiple fees. He personally did most of this kind of selling in Vienna and in London, but hired middlemen for additional markets. He also earned a bit of extra cash by selling manuscript copies of new works to private individuals. These so-called “subscription copies” carried a good deal of prestige for the buyer, and Haydn was happily wheeling and dealing. Take his famous string quartets Op. 33 as an example. The works were composed in the summer and autumn of 1781 and already sold to the publisher Artaria by prior arrangements.

Hanover Square

Nevertheless, in December 1781, Haydn wrote to about 20 noble and rich music lovers, including the Swiss intellectual Johann Caspar Lavater. “I love and happily read your works … Since I know that in Zürich and Winterthur there are many gentlemen amateurs and great connoisseurs and patrons of music, I cannot conceal from you the fact that I am issuing a work consisting of 6 Quartets for two violins, viola and violoncello concertante, by subscription for the price of six ducats; they are of a new and entirely special kind, for I haven’t written any for ten years … Subscribers who live abroad will receive them before I issue the works here in Vienna.”

Franz Joseph Haydn: String Quartet No. 30 in E-flat Major, Op. 33, No. 2 “The Joke” (Borodin Quartet)

The publisher Artaria, meanwhile, unaware of Haydn’s shady dealings, announced the forthcoming publication of the quartets on 29 December. Haydn was furious and wrote, “It was with astonishment that I read … that you intend to publish my quartets in four weeks … Such a proceeding places me in a most dishonourable position and is very damaging; it is a most extortionate step on your part … Mr Hummel [the publisher] also wanted to be a subscriber, but I did not want to behave so shabbily, and I did not send them to Berlin solely out of regard for our friendship and further transactions; by God! You owe me more than 50 ducats, since I have not yet satisfied many of the subscribers, and cannot possibly send copies to those living abroad; this step must cause the cessation of further transactions between us.” In the event, Artaria relented and delayed publication until April 1782 and Haydn sold the quartets to Hummel after all. “Next time” Haydn sheepishly wrote to Artaria, “we shall both be more prudent.”

Franz Joseph Haydn: String Quartet No. 32 in C Major, Op. 33, No. 3 “The Bird” (Eybler Quartet)

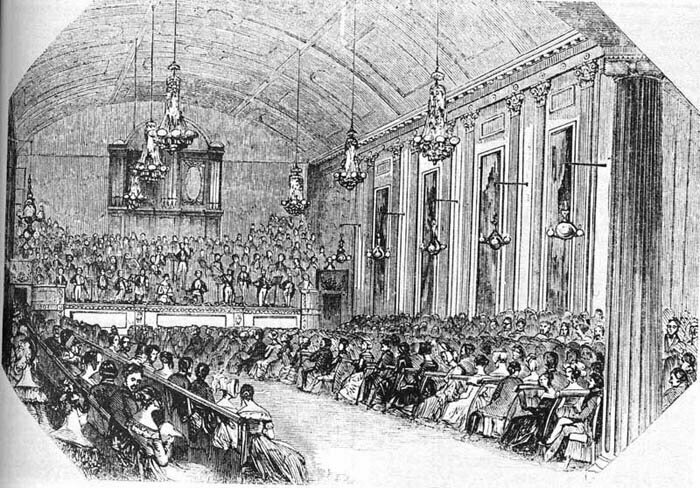

In terms of personal happiness, professional recognition and financial benefits, Haydn’s London visits were the highpoints of his career. As he subsequently wrote, “I considered the days spent in England the happiest of my life.” He had a passionate love affair with Rebecca Schroeter, widow of the composer and pianist Johann Samuel Schroeter, he was treated like royalty, and he received an honorary doctorate of music at Oxford. And let’s not forget he did make a shedload of money. His initial contract with the impresario Salomon guaranteed, “£300 for an opera, £300 for six symphonies, £200 for the rights to publish the latter, £200 for 20 other compositions to be conducted at his concerts and £200 profit from a ‘benefit’ concert.” Haydn hadn’t taken much music with him, and he basically composed everything he needed on the spot. When all was set and done after two highly successful trips to England, Haydn reportedly earned 24,000 gulden and netted 13,000, which equated to more than 20 years of his salary at the Esterházy court.

The concert rooms at Hanover Square

It would be all too easy to classify Haydn as a ruthless money grabber. Outside the world of business, however, he was a very generous man. He supported his brother Johann for decades, gave substantial sums of money to relatives and servants, and volunteered his services for charitable concerts. He even offered to teach the two infant sons of Mozart for free after their father had died.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 96 in D Major, “The Miracle” (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Georg Solti, cond.)