Specifically known for his historically informed performances of music from the Classical era, Nikolaus Harnoncourt was born in Berlin on 6 December 1929. His full name actually reads Johann Nikolaus Graf de la Fontaine and d’Harnoncourt-Unverzagt, a lineage passed on from his father Eberhard Harnoncourt, a count of Luxembourg and Lorraine. His mother Ladislaja, née Gräfin von Meran and Freiin von Brandhoven, was Austrian. She was the great-granddaughter of the Habsburg Archduke Johann, and the 13th child of Emperor Leopold II. As such, Nikolaus Harnoncourt is a direct descendant of a Holy Roman Emperor.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt

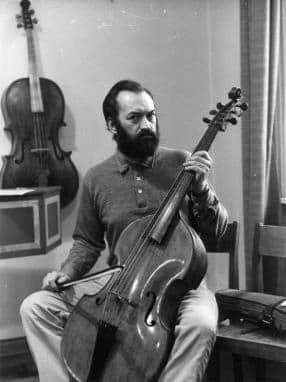

Eberhard Harnoncourt was employed as an engineer in Berlin, but he quickly took his family to Graz, in the southern Austrian state of Styria, where he secured a post in state government. Eberhard was an enthusiastic amateur musician. He was determined that all his children should learn to play musical instruments, and he even composed sonatas and chamber music for them. Eberhard played the piano, his sons René and Philipp played the violin, and young Nikolaus the cello.

Concentus Musicus Wien Performs Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 “Allegro”

Nikolaus had a number of talents and interests, which included wood carving and sculpture, and he proudly created his own marionette theatre. In addition, he quickly became an accomplished cellist and decided on a career in music during the autumn of 1947. While he was sick and lying in bed one day, he heard a radio recording of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony under Wilhelm Furtwaengler, and his mind was made up. He enrolled as a cello student of Prof. Emanuel Brabec at the Vienna Academy of Music.

Nikolaus and Alice Harnoncourt

Harnoncourt remembered, “I was 18 when I came to Vienna and I was not prepared for the mixture of cultures. I came in like a peasant and the Viennese are not very polite to the provincials. I found a little flat in a building owned by the Benedictines with a staircase from the 16th century. And so I went up and down the staircase and my legs felt the rhythm of the 16th century because there were no bad architects at that time.”

Johann Sebastian Bach: Concerto for Oboe and Violin, BWV 1060

As a student in Vienna, Harnoncourt developed a distinct interest in early music. He took courses in early music under Josef Mertin in Vienna, and among his colleagues was the violinist Alice Hoffelner. She had studied under Ernst Moravec and Gottfried Feist in Vienna, and then with Jacques Thibaud in Paris and Tibor Varga in London. Together with Alice, Harnoncourt founded his first early music ensemble, the Vienna Viola da Gamba Quartet, and he never graduated from the conservatory. Instead, he accepted a position playing in the Vienna Symphony Orchestra under Herbert von Karajan in 1952, and remained with the orchestra until 1969.

Concentus Musicus Wien

Alice and Nikolaus married in Graz in 1953, and in the same year, they founded a group to perform Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. Paul Hindemith conducted that performance and the ensemble became known as “Concentus Musicus Wien.” Harnoncourt remembers that they “found a little flat in the Vienna Josefstadt, owned by the family of the scientist Karl Frisch. The four Frisch brothers formed a string quartet, and invited Brahms to play with them. The Frisch widow remembers that her husband played the violin very badly, and that Brahms was an ugly little man with his squeaking high voice and he was absolutely not nice to us.”

Concentus Musicus Wien Performs Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046

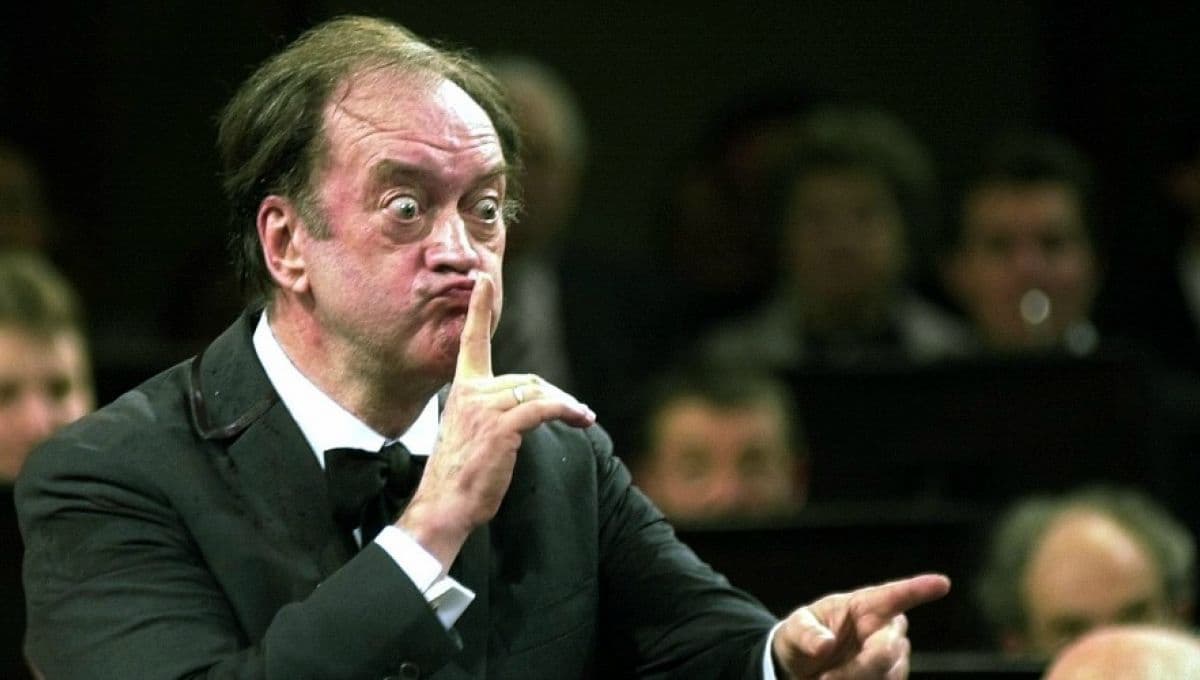

For the Harnoncourt’s, however, “it was almost holy to live in a flat where Brahms was every 2 weeks playing piano and it was as if the waves of his piano playing were still there.” Concentus Musicus, which Harnoncourt called “a fellowship of explorers,” was founded in that very room, and it served as the rehearsal space for the ensemble for 17 years. It also served as the intellectual space that helped to formulate his theories on historically informed performance practices. As he later explained in his 1982 publication Music as Speech, the emphasis was placed on making music that developed from original sources. “He demanded that his musicians be ready to discuss, that they ask questions; indeed, he expected objections.”

According to scholars, “this automatically made him the antithesis of the traditional conductor who never justifies his decisions to the lower orchestra musicians.” Early performances by Concentus were mostly private and critics were initially hostile, commenting on the lack of brilliance in the musical sound and on the shortcomings of the older wind instruments. However, their reputation steadily grew, especially after they issued a recording of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos in 1962. Wishing his concert audiences “not a nice evening but a stirring one,” Harnoncourt remained true to his cause of “counteracting aesthetically sanitized music making.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Concentus Musicus Wien Performs Mozart’s Requiem in D minor, K. 626