Pietro Mascagni

Pietro Mascagni wrote fifteen operas, an operetta, several orchestral and vocal works, and also songs and piano music. However, he will always be remembered for his 1890 masterpiece Cavalleria Rusticana. Considered the first verismo opera, Cavalleria Rusticana mirrored the Italian literary movement of the same name and portrayed the world with great realism. With its operatic introduction to a regional milieu, in this case, a small town in Sicily, local customs and lower-class idioms, it became the prototype of an entirely new genre. Based on a play by Giovanni Verga, the religious celebration of Easter provides the backdrop for Turiddu’s declaration of love for Lola, who is married to Alfio. To soothe his pain, Turiddu seduces the young Santuzza. However, when Lola decides to become Turiddu’s mistress, Santuzza not only curses her seducer but also discloses Lola’s infidelity to Alfio. Alfio insults Turiddu and eventually challenges him to a duel. Turiddu entrusts his mother to look after Santuzza, and he is promptly killed in the fight.

Pietro Mascagni: Cavalleria Rusticana, “Intermezzo”

Cavalleria rusticana at the opera’s world premiere,

17 May 1890, Teatro Costanzi, Rome

The overwhelming success of Mascagni’s opera took European opera houses by storm. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky first heard the opera in Warsaw in 1891. Thoroughly impressed, he wrote, “The opera house in Warsaw is really quite good. Yesterday I saw for the first time the celebrated Cavalleria Rusticana. This opera is indeed very remarkable and especially so thanks to the amazingly felicitous choice of subject. I wish Modest would be able to find me a subject of this kind.” According to Modest, when Tchaikovsky visited Vienna in September 1892, “the hotel room in which he was staying happened to be next to the room of Pietro Mascagni, who was then at the peak of his fame in Europe… Finding himself next door to him in the same hotel, he wanted to make the acquaintance of his young colleague, but when he saw in the corridor a whole string of admirers waiting to be received by the young maestro, he decided to do him a favor by not burdening him with an extra visit.”

Pietro Mascagni: Cavalleria Rusticana, “Regina Coeli”

Stagno and Bellincioni in Cavalleria Rusticana,1890

When Tchaikovsky was asked to comment on the state of music in Italy, he responded, “Until very recently the art of music in Italy was still in a state of great decline. But it seems that now we are witnessing the dawn of its rebirth there. A whole pleiad of talented young composers has emerged, and amongst these it is Mascagni who, quite rightly, attracts the most attention… Mascagni is evidently not just a very gifted man, but also very intelligent. He has understood that nowadays the spirit of realism is in the air everywhere, that is the drawing together of art and the truth of life; he has realized that all these Wotans, Brünnhildes, and Fafners are at the bottom incapable of awakening keen sympathy in the listener’s mind, that man with his passions and misfortunes is closer to us and more understandable than the gods and demigods of Valhalla. Judging from his choice of subjects, Mascagni proceeds not by means of instinct, but rather by dint of a profound understanding of the needs of the modern listener.”

Pietro Mascagni: Cavalleria Rusticana, “Addio alla Madre”

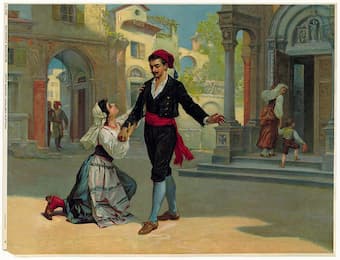

The scene where Santuzza meets up with Turiddo outside the church

With Cavalleria Rusticana becoming the prototype of a new genre, verismo witnessed a flowering of operas in Italy and abroad. A Neapolitan brand of operatic verismo was instigated by Giordano’s Mala vita “Wretched Life” of 1892. “The sordid conditions in the alley of a big city and the wretched life of a prostitute were transported to the operatic stage without softening their crude reality.” Leoncavallo followed up with his famous veristic opera Pagliacci, “and Italy’s poor regions were exploited by the opera industry for the productions of stage works with a tendency to lapse into picturesqueness and sensationalism.”

Pietro Mascagni conducting

The veristic fashion spread to France with Massenet composing La Navarraise in 1894. In Germany, Eugen d’Albert wrote Tiefland “Lowland” a two-act opera set in Catalonia. Frédéric d’Erlanger composed Tess after the Hardy novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles, and Janáček’s Jenůfa of 1904 also belongs to the verismo genre. In 1940, Cavalleria celebrated its 50th anniversary, and Mascagni was in great demand as the conductor. The priest and musician Licinio Refice called Mascagni, “the musical lymph of pure Italianity; flame of the intact Italian tradition of melodrama; a vigilant sword to protect the artistic strength of the Italian race.” Mascagni died on 2 August 1945 in his apartment at the Grand Hotel Plaza in Rome, and the funeral ceremony was held on 4 August.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Pietro Mascagni: Cavalleria Rusticana