A cartoon from Austrian magazine Die Muskete,

depicting Mahler with a variety of

musical and pseudo-musical devices

Gustav Mahler conducted the premier performance of his 6th Symphony on 27 May 1906 at the Saalbau Concert Hall in Essen. It was conceived and composed during a period of great personal happiness and professional success. In 1902 he had married Alma Schindler, Vienna’s most eligible bachelorette, and by 1904 a second daughter, Anna Justine, was born. Mahler had also assumed directorship of the Imperial Opera in Vienna, and his productions elicited high praise from audiences and critics alike. His association with the supreme stage and costume designer Alfred Roller spawned more than 20 celebrated productions, and his administrative involvement restored financial stability to the organization. Although his Viennese tenure, which would last until November 1907, was a period of repeated battles with performers, administrators and a hostile press, it nevertheless represented one of the most satisfying decades in his professional life. In addition, his own compositions received more frequent performances, and while his symphonies only gradually gained public acceptance, his songs were comparatively well liked. Given his personal happiness and professional success, how are we to explain the meaning of his Sixth Symphony, one of the most disturbing, menacing and unrelenting compositions to emerge from Mahler’s imagination?

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A minor, “Allegro”

Composing hut of Mahler

Mahler began work on the Sixth in the summer of 1903. Taking his holiday in the tiny village of Maiernigg on the Wörthersee, located in the Austrian province of Carinthia, he quickly drafted two movements and eventually completed the work in 1904. Supremely confident in his craft, Mahler hoped that this new symphony would further convert audiences to his music. Unfortunately, it was flatly rejected, and the Viennese critic Heinrich Reinhardt quipped “Brass, lots of brass, incredibly much brass! Even more brass, nothing but brass”! Clearly, the critical rejection of this work was not simply a matter of orchestration, but emerged from the tragic and bitter pessimism contained in the music. Although this attitude was not a reflection of his personal life, it was an expression of the enormous political and cultural changes that flooded Europe in the first decade of the 20th century. As the dismantling of political, social and artistic structures inexorably accelerated towards the catastrophes of World War I, Mahler’s music “expressed the intuitive forebodings of an artist listening to the distant rumbles of the future and, as such, formulated the apprehensions of the suppressed and inarticulate.”

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A minor – II. Scherzo: Wuchtig (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; Bernard Haitink, cond.)

Young Alma Mahler

A critic wrote, “it is the juxtaposition of Mahler’s prophetic visions of death and destruction with his idyllic personal love for family and nature that gives rise to an outpouring of emotions in a symphony constrained by classical formal procedures and thematic unification.” We can easily hear this uneasy duality in the opening “Allegro.” A brief introduction, ominously growing in dynamic intensity, establishes the minor key and foreshadows the menacing march-like first theme. This theme, characterized by jagged leaps in the strings, is superimposed over a chilling, and recurring motif. Over the pounding rhythm of the timpani, three trumpets sound an A major chord that abruptly collapses into minor. This unsettling musical gesture, which will return in subsequent movements and unify the composition, dominates the transitional area before the music abruptly disintegrates into stillness. The musical contrast, supposedly representing Alma, emerges after a quiet chorale in the woodwinds. Lush strings sing a broad melody that is only momentarily interrupted by a staccato march, and the return of the “Alma” theme.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A minor – III. Andante moderato (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Herbert von Karajan, cond.)

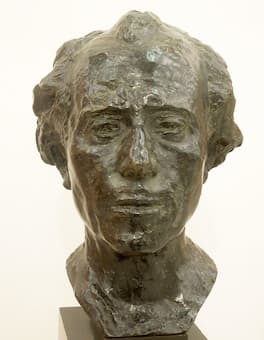

Auguste Rodin: Gustav Mahler, 1909

Given the earnestness with which Mahler approached his 6th Symphony, it is somewhat surprising that he could not decide on the order of the middle movements. The autograph and first printing placed the “Scherzo” before the “Andante,” whereas Mahler’s own public performances and the second published edition reverses that order. Mahler apparently changed his mind once more, yet the debate as to the order of movements continues. The Scherzo has been characterised as having a “sinister artificiality,” and it is juxtaposed by a “Trio” that Alma described as “the stumbling play of children.” We finally experience a sense of respite, as the “Andante” is a set of variations in the major key. Emotionally overwhelming, the concluding “Allegro” descends into a nebulous chaos as strings recite aimless musical fragments that brutally collide with a major-minor motive sounded in the trumpets and trombones. The music is cut short by the brutality of the infamous hammer blow of fate that Mahler wanted to sound like the stroke of an axe. The next wave of marches, this time in a confident major key restlessly strives towards new heights. However, the second hammer blow of fate quickly extinguishes any hope of resolution. The music, once more builds towards a third and final climax but without the final hammer blow. Fragments of eerie funeral tunes are sounded in the low brass over extended drum rolls that plunge the movement into utter darkness, all ending in deepest despair and gloom.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A minor, “Allegro”