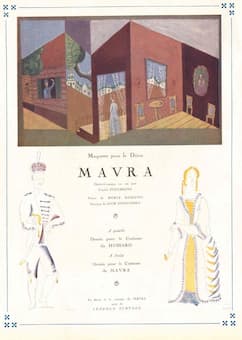

Program page for Mavra (1922)

To begin his new neo-classical period, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) took a story by Alexander Pushkin and had Boris Kochno, Serge Diaghilev’s personal secretary, create a libretto for a little one-act comic opera. In Pushkin’s poem, a widowed mother and her daughter live with their cook who suddenly dies of pneumonia. They must have a cook and so hire a new girl, Mavra, tall but in humble clothing, asking little in the way of a salary. But she wasn’t the cook they’d had before – she broke the plates, burned the roast, and when she tried a ragout, it ran away in lumps. She couldn’t sew, either. One Sunday the family goes off to church while Mavra stays home to start the baking since she had overslept. The mother, not trusting her to bake (since she couldn’t bake yesterday), thinks she’s stayed home to rob the house. Arriving home, she sees Mavra standing in front of the daughter’s mirror…shaving! Mother screams and Mavra departs at speed, still foamed up and with a white towel across his face, never to be seen again. The daughter may blush at this point (the narrator doesn’t quite say) and the story ends.

Stravinsky wrote his opera in 1922 and it was given its premiere in Paris at the Théâtre de l’Opéra Paris. The small opera failed on the large stage but remained a favorite of Stravinsky. The work received its US debut in 1934 in Philadelphia.

Igor Stravinsky: Mavra – Overture (CBC Symphony Orchestra; Igor Stravinsky, cond.)

The opera changes the story to make it more personal – Parasha, the daughter, sees the neighbor Vasili, a hussar, through the window and conspires to bring him into the house to replace the old cook, who has died. Parasha and Vasili are successful in their duplicity until mother and daughter return early and discover the new cook shaving. They yell, the neighbor comes to help, and Vasili jumps out the window in his panic. The opera ends with Parasha lamenting her lost hussar. The difference is that Parasha is made the vehicle for Vasili’s knowing entrance into the house, whereas in Pushkin’s story, it’s left a bit vague.

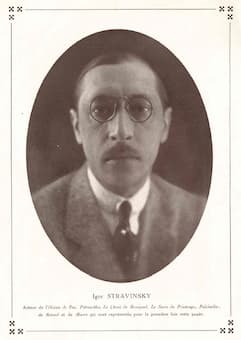

Igor Stravinsky from the 1922 Ballets et

Opéras Russes de Diaghilev program

Through this work, Stravinsky was making a statement against the old Mighty Five of Russian music. Rimsky-Korsakov, a member of the Mighty Five and Stravinsky’s teacher, was important in the Five’s creation of a Russian native style. The Five were fond of using whimsical Russian folk tales filled with fairies and magic. In Mavra, Stravinsky took their fuel source (a folk tale) but one by an author he felt the Five had ignored, Alexander Pushkin. To Stravinsky, Pushkin was a ‘classical Russian,’ and by using him for source material, Stravinsky sought to ‘unite the most characteristically Russian elements with the spiritual riches of the West.’

Stravinsky used a Russian tale but used a music setting based on the Italian 18th-century opera buffa style. Unfortunately, Russian syllables are more difficult to set in a flowing manner than Italian syllables and this remained a challenge for Stravinsky. The work was dedicated by Stravinsky to ‘the memory of Pushkin, Glinka, and Tchaikovsky,’ while at the same time creating a satire on bourgeois manners, cute romantic stories, and the kinds of themes that his predecessors had been so fond of.

The opera has two arias, a duet, and closes with a quartet of the mother, her daughter, the neighbor and Mavra.

Pasrasha’s song, very much in a Russian style with an Oom-pah bass.

Igor Stravinsky: Mavra – Drug moy milyy (Susan Belinck, Parasha; CBC Symphony Orchestra; Igor Stravinsky, cond.)

Vasili makes his entrance with a military hussar song.

Igor Stravinsky: Mavra – Kolokol’chiki zvenyat (Stanley Kolk, Vasili; Susan Belinck, Parasha; CBC Symphony Orchestra; Igor Stravinsky, cond.)

The Mother’s song has a new style entirely, but still very Russian.

Igor Stravinsky: Mavra – Izbavi Bog prislugu (Patricia Rideout, Mother; Susan Belinck, Parasha; CBC Symphony Orchestra; Igor Stravinsky, cond.)

The final quartet, where all is revealed and Vasili/Mavra makes his exit, seems to end without a real finality.

Igor Stravinsky: Mavra – Pozhaluy vremya nastupilo pobrit’sya Patricia Rideout, Mother; Mary Simmon, The Neighbor; Stanley Kolk, Vasili; Susan Belinck, Parasha; CBC Symphony Orchestra; Igor Stravinsky, cond.)

In the program for the debut, part of a program for the entire May-June 1992 presentation of the Ballets et Opéras Russes de Diaghilev, we have a picture of the young Stravinsky.

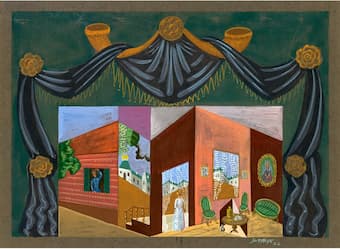

Survage: Stage design for Mavra (1922) (Harvard University: Houghton Library, Howard D. Rothschild Collection.)

The original costumes were by Léopold Survage (1879-1968), a French painter who had trained in Moscow and who did work for the Ballets Russes. Originally intended to work in his father’s piano factory in Finland, he studied piano and then studied painting and when he went to France in 1908, he had a dual career as a piano tuner and artist, first showing his artwork in 1911. He became an abstract painter and shared rooms with Amadeo Modigliani in Paris before moving to Nice. His first work for Diaghilev were the stage and costume designs for Mavra.

The orchestra for the opera was unusual in that it consisted of a string quintet and 22 woodwinds and brass instruments, plus timpani – this would be influential going forward in changing the traditional opera orchestra’s makeup.

Although Mavra was an initial failure and closed after only seven performances, in its quiet way it was more influential than it might appear at first glance: it permitted Stravinsky to break away from the cloying Russian style (which he had already tried to stomp to death in The Rite of Spring), it changed the orchestral makeup, it brought new and influential abstract painters to the stage, and it was a rare opera where it was the woman who got her own way sexually, rather than being at the service of more powerful men.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Pushkin’s original poem was filmed as a 1913 silent movie in Russia