Josquin des Prez

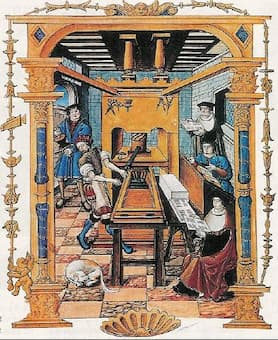

A good many performing artist today are known by a single name. There is Beyoncé and Lola, Madonna and Sting, Cher and Hauser. And we might make an exception and include Lang Lang in this list. These celebrities are so famous they really only need one name. The same was true of Josquin des Prez (c. 1450/1455-1521), who over the last 500 years has simply been known as Josquin. Josquin appeared well respected during his life, but things got started in earnest when the Venetian printer Ottaviano Petrucci started using movable type in his print production in 1502 and issued polyphonic music of outstanding quality. His printing technique required three impressions. Each sheet of music would be run through the presses once for the staves, once for the music, and once for the words. In all, 61 music publications by Petrucci are known, and Josquin became his pre-eminent composer. When he issued his first four motet anthologies, each one was prominently headed by a Josquin motet.

Josquin des Prez: “Alma redemptoris”

Josquin: Adieu mes amours

In a stroke of genius, and for the first time ever, Petrucci decided to devote an entire collection of music to a single composer. In 1502 he issued a dedicated volume of mass settings by Josquin, which proofed highly successful. He followed up with a second volume of masses by Josquin in 1505, and reprinted his first volume. A third mass collection was issued in 1514, with both previous volumes reprinted again. Petrucci had made Josquin a brand name, and printers throughout Europe rushed in to profit from this name recognition. The Antwerp printer Susato issued Josquin chansons, which were reprinted with some additional works by Attaingnant in Paris. The Parisian firm of Le Roy & Ballard issued a volume of motets by Josquin, and German publishers in Nuremberg and Augsburg printed many pieces under Josquin’s name.

Josquin des Prez: Missa L’homme arme (Oxford Camerata; Jeremy Summerly, cond.)

This kind of superstardom and immense prestige accorded to Josquin, however, brought with it a number of problems. “Many scribes and publishers did not resist the temptation of attributing anonymous or otherwise spurious works to Josquin.” The German editor Georg Forster summed up the situation in 1540 when he wrote, “I remember a certain eminent man saying that, now that Josquin is dead, he is putting out more works than when he was alive.” Placing the name Josquin on a score was guaranteed to stir interest and sales, and at one time or another, over 300 pieces were ascribed to Josquin. Recently, musicologists and scholars have excised dubious works from the catalogue, and we seem to be left with a new total of about 103 works. “Mille regretz” is one of the best-known chansons attributed to Josquin, but this attribution only appears in a Susato print issued as late as 1549. In other print sources it bears the name J. Lemaire, possibly referencing not to the composer but the author of the text. At any rate, a good many works of Josquin are now disputed on stylistic grounds or problems with sources or both.

Josquin des Prez (J. Lemaire): “Mille Regretz”

A printing workshop

The real problem with Josquin attributions is the fact that no original manuscripts have survived. Instead, everything exists in handwritten copies, which were then used as the basis for printing. Even Petrucci did not look at original manuscripts for his editions, but consulted secondhand sources. And in a good many cases, multiple copies of the same piece exist in different geographic locations, many of them showing musical variations or even mistakes copied from somewhere else. In addition, scribes frequently added Josquin’s name to pieces that had previously been anonymous. And once you have to exclusively rely on stylistic evidence, the process of attribution becomes a veritable minefield, as the process of separating the real from the imitation is an arduous process. Removing questionable attributions is one thing, but in the end we might be left with a substantial number of pieces by Anonymous X. What we can learn from this process, however, is the fact that music before 1600 cannot be conclusively linked to one exceptional individual. Josquin was part of a pool of talented musicians that shared a common language, but what his name “gave to music was the honor of a lineage.”

Josquin des Prez: “O virgo virginum” (Orlando Consort)

Josquin: In principio erat Verbum

Josquin acquired the reputation of the greatest composer of the age in the 16th century, “his mastery of technique and expression universally imitated and admired.” Writers and theorists considered his “style as that best representing perfections.” His standing within his own time is probably best gauged by the number of laments composed immediately following his death. A wonderful musical tribute from a later generation is Jacquet of Mantua’s motet “Dum vastos Adriae fluctus.” The middle section “included the titles of several motets by Josquin, setting the words to free but recognizable variants of Josquin’s own music, and making it clear how highly he was regarded in Italy a generation after his death.” Josquin’s fame reached all the way into the early Baroque, and interest in this superstar composer has been revived in the 20th century. Looking at him with fresh eyes, we still find an astonishing composer of dazzling contrapuntal facility who lived among a community of fantastic Renaissance artists. Josquin’s biggest legacy might well be the fact that unbeknownst to himself, he accorded music the same level of importance granted to painting and to architecture.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Jacquet of Mantua: “Dum vastos Adriae” (The King’s Singers)

If you study the Gustave Soderlund system you will learn Renaissance music analysis well enough to be able to distinguish one composer from another.

For example, Josquin favors the incomplete Cambiata, and this can be taken as an indication of authorship.