© mencheymusic.com

The end of January sees the UK deadline fast-approaching for self-employed people up and down the country to submit their ‘Self Assessment’ tax returns. Sight reading, much like filing tax forms, is something that makes sense in theory, but can strike terror into the hearts of those undertaking it. Is sight reading difficult? Yes, it can be. Does it have to be? No, not at all. Am I writing this in order to procrastinate from doing my own tax return? Of course not.

Sight reading: the ability to play music that you’ve never seen before…

Sight reading – or the ability to play music that you’ve never seen before – can seem like witchcraft from the outside: plonk down a sheet of music in front of someone and off they go, performing without a care in the world – or without a moment’s practice.

You might protest: ‘But wait a minute! My teacher always tells me to practise and you’re sat here telling me you can play things without ever having seen them?!’ Before you set your teacher on me for corrupting you away from the virtues of practice, rest assured that practice still has to happen (sorry for getting your hopes up there). Just like having your accounts in order helps you feel prepared when submitting your tax return, being in good shape on your instrument is essential in order to be able to sight read, otherwise you might just find it too… taxing. I know, I know, sorry. Look: it’s either this or doing my taxes, ok?

Saint-Saëns: The Swan

Saint Saëns’ ‘The Swan’ from Carnival of the Animals, something that is on the more doable end of the sight reading spectrum

Sight reading certainly is a skill in its own right, a skill which should be applied sensitively and carefully in the proper context. Given that the payoff seems so great (not having to practise or rehearse so much), why does sight reading give us the heebie-jeebies? Why is it so scary? And, perhaps most importantly, why should we embrace it?

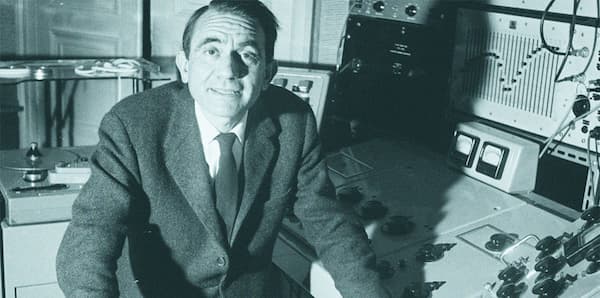

The amount to which a professional musician needs to sight read varies depending on the career route they end up pursuing. Certain orchestras and groups build in lots of rehearsal time to their schedules, giving everyone lots of time to practice and learn the music gradually. However, with certain freelance positions, this time is often not there. This goes particularly for recording sessions, when it is fairly common to turn up on the day having never seen the music before. The red light goes on and you have to deliver, the music having just been printed that very morning.

Who can sight read?

Fear not, though: you don’t have to be a professional musician jumping into the shark tank of a high-pressure recording session to be able to sight read. Sight reading is a natural part of learning an instrument, and everyone can already sight read to a greater or lesser degree.

Debussy: Prelude No. 6 Des pas sur la neige

Debussy’s Des pas sur las neige from his first book of preludes. Not recommended for sight reading, but probably doable at a push

If you think you’re terrible at sight reading, consider this: in your first ever lesson, chances are that a considerable amount of your attention was spent on where to put your fingers to obtain a certain note. As you practised and developed, you maybe had to think slightly less on how to produce the same notes, freeing up some brain space for other activities, one of which may have involved being able to look ahead in your score and anticipate which notes were coming while currently playing something else: in other words, sight reading.

You may already be sight reading a little more than you think. Everyone starts to sight read things without realising, as skill is gradually developed on an instrument. Professional musicians find it easier to sight read just because they’ve spent more time practising and therefore don’t need to think so much about the more technical issues, meaning their headspace is freed up for other things.

Ravel: Gaspard de la Nuit, No. 1, “Ondine”

Ravel’s ‘Ondine’ from Gaspard de la Nuit. Fairly unequivocally out of the range of sight reading (in case you ever wondered if you ever needed to practise again…)

© learnmusictogether.com

Sight reading, however, is not simply a natural extension of good practice, and even professionals have trouble with it sometimes. Certain people have more of a knack for it than others – but that’s not to say that it can’t be improved. Even those of us who are lucky to be able to sight read well shouldn’t use it as a substitute for actual practice – there are some crucial differences between the two.

So before you throw down your instrument in protest at practice, relying only on the virtues of sight reading, remember that it has to be learned and practised like any other skill. And with that, we come to the end of this article, and the inevitable end to my procrastination. Right, I can’t put this off any longer. Where’s my calculator…

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Sight reading is not sight reading, it is sight remembering. I learned this as a studio guitarist. Try sight reading a particularly hard part that has groups of notes arranged in a way you have never encountered before. Then try sight reading a part with a group of notes you have never encountered before but are assembled in a way you have seen. You can immediately see the difference. I learned this from a wonderful pianist with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. I have forgotten her name but she called everyone Bubibala. She said, when asked, bu bula, I have memorized all classical music. What could anyone write that I don’t know? She sight remembers anything that was thrown at her and I’ve seen her do it.