Castration for musical reasons was never really officially legal. In fact, it was banned under Canon Law and punishable with excommunication. The music historian Charles Burney traveled through Italy in search of places where the operation was carried out. He writes, “I enquired throughout Italy at what place boys were chiefly qualified for singing by castration but could get no certain intelligence. I was told at Milan that it was at Venice; at Venice that it was at Bologna; but at Bologna, the fact was denied, and I was referred to Florence; from Florence to Rome, and from Rome, I was sent to Naples.” Most castrati would not speak of their castration, with the exception of Filippo Balatri (1682-1756).

Charles Burney

In his autobiography he reports, “My voice was found to be of the finest texture, with a natural and well-performed trill, great agility in roulades and a natural taste in singing. For this reason, my father’s friends started recommending Cut, Cut, and the Maestro added his voice to theirs. My father finally agreed, and I was sent to Accoramboni, a surgeon in Lucca, to spend two months in his home, where I would enjoy much delightful conversation. This period of conversation was so bewitching that, instead of earning the title of doctor, I received a patent to present myself as one of the ‘frigidis et malificiatis’ for the rest of my life. And now I will never hear that sweet word ‘father,’ which I might one day have heard.” Attributed to Benedetto Marcello, the “Lament of the Castrati” alludes to the advantages and disadvantages of having intercourse without a resultant pregnancy.

Benedetto Marcello: “Lamento del castrati” (San Petronio Cappella Musicale Soloists; Sergio Vartolo, cond.)

Filippo Balatri

It was erroneously assumed that castration automatically created great singers. Sadly, that was not the case as “a certain degree of vocal and musical talent was required, though this was something that many a poor parent, blinded by the money-making potential of the operation, seemed to forget.” Charles Burney commented, “the church choirs of Italy were filled with castrati who were rejected from the opera houses.” Valentino Urbani (1690–1722), nicknamed “Valentini,” did make it onto the operatic stage. He was born in Udine and eventually entered into the services of the Duke of Mantua. In 1690, he first appeared in Venice and Parma, and he also sang in Bologna, Piacenza, Ferrara, and Rome. For three years, between 1697 and 1700, he was in the service of the Electress of Brandenburg in Berlin.

Valentino Urbani, nicknamed “Valentini”

Valentino was the first castrato to sing regularly in London, and he made his début at Drury Lane in 1707. He sang in many different pasticcios and several bilingual operas, and he had a benefit concert each year. Valentino also sang for George Frideric Handel. He appeared in the role of “Eustazio” at the première of Handel’s Rinaldo, the role of “Silvio” at the premiere of Il pastor fido, and the role of “Egeo” at the first performance of Teseo. By the time he took on his Handel parts, Valentini’s power seemed to have been on the decline. Charles Burney noted that “from those who frequented operas at this time, Valentini’s voice was feeble, and his execution moderate.” However, his acting was still praised enthusiastically. Valentini last appeared in public in Hamburg in 1722.

George Frideric Handel: Rinaldo, “Col valor, colla virtu” (Marion Newman, mezzo-soprano; Laura Whalen, soprano; Kimberley Barber, mezzo-soprano; Jennifer Ens Modolo, mezzo-soprano; Sean Watson, baritone; Barbara Hannigan, soprano; Giles Tomkins, bass-baritone; Nicole Bower, soprano; Catherine Affleck, soprano; Melinda Delorme, mezzo-soprano; Lenard Whiting, tenor; Opera in Concert; Aradia Ensemble; Kevin Mallon, cond.)

Giovanni Carestini, nicknamed “Cusanino”

Giovanni Carestini (1700-1760) performed under the name “Cusanino” and he frequently commanded a higher fee than the famous “Caffarelli.” His voice, according to contemporary reports, “began as a powerful and clear soprano, and later descended to the fullest, finest, and deepest counter-tenor that has perhaps ever been heard.” The composer and famed singing teacher Johann Adolph Hasse commented, “he who has not heard Carestini is not acquainted with the most perfect style of singing.” And Johann Joachim Quantz added, “He had extraordinary virtuosity in brilliant passages, which he sang in chest voice, conforming to the principles of the school of Bernacchi and the manner of Farinelli.” By all accounts, he had strikingly good looks, sporting “a handsome and majestic profile,” and he was considered a fine actor.

Carestini’s career started in Milan in 1719, and since the Cusani family sponsored him, he took on his nickname “Cusanino.” He sang for Alessandro Scarlatti in Rome and appeared at the Viennese court in 1723. With his reputation growing rapidly, he sang in operas by Hasse, Vinci, and Porpora in Naples, Venice and Rome. Vinci and Metastasio created virtuoso roles for him, and Cusanino crossed the Alps in 1731 to enter the service of the Duke of Bavaria in Munich. In 1733, he came to London to sing for Handel. Handel created the principal male roles in Arianna in Creta, Parnasso in festa, Terpsichore, Ariodante and Alcina, and he was also singing in the oratorios Deborah, Acis and Galatea, Esther and Athalia. According to an anecdote reported by Charles Burney, Carestini sent back the aria “Verdi Prati” from Alcina “as unfit for him to sing.” Apparently, Handel went into a great rage and yelled at the singer, “I know best what’s good for you to sing. If you don’t sing the songs I give you, you won’t get paid.”

George Frideric Handel: Alcina, “Verdi Prati” (Jochen Kowalski, counter-tenor; Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Chamber Orchestra; Hartmut Haenchen, cond.)

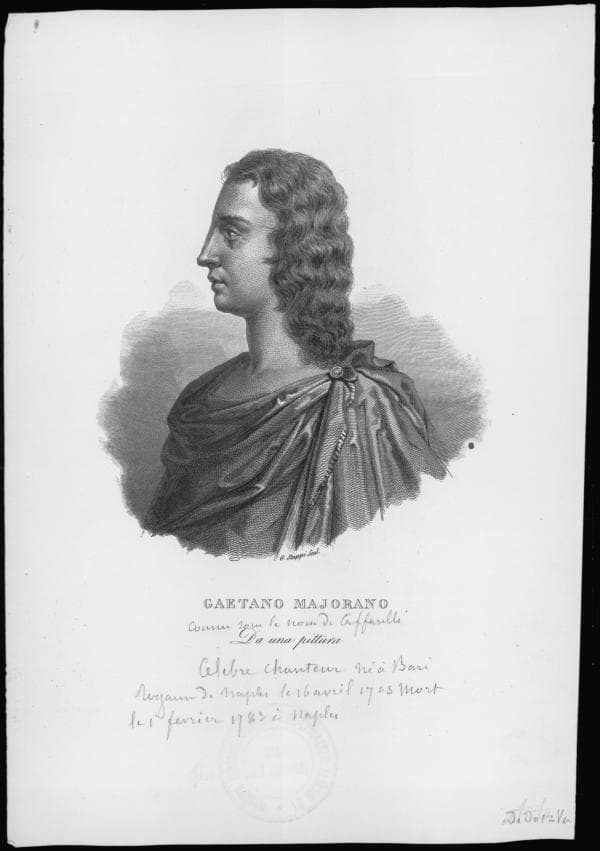

Gaetano Majorano, nicknamed “Caffarelli”

A good many contemporary critics considered Gaetano Majorano (1710–1783), nicknamed “Caffarelli,” the greatest singer Italy had ever produced. “It would be difficult to give any idea of the degree of perfection to which this singer has brought his art,” writes an observer. “All the charms and love that can make up the idea of an angelic voice, and which form the character of his, added to the finest execution, and to surprising facility and precision, exercise an enchantment over the senses and the heart, which even those least sensible to music would find it hard to resist.” It is said, that at the age of ten, Gaetano inherited the income from two vineyards owned by his late grandmother, “so that he could study music, to which he is said to have a great inclination.” Apparently young Gaetano decided to “have himself castrated and become an eunuch.” In the event, he studied with the famous singing teacher Nicola Porpora and took on the stage name “Caffarelli,” paying homage to the maestro of the church in which he sang as a child, “and who may well have been responsible for helping him to find a surgeon.”

Caffarelli made his debut at the age of sixteen in Rome, and he quickly appeared in theatres throughout Italy. He made his début at the King’s Theatre in the pasticcio Arsace and created the title roles in Handel’s Faramondo and Serse. His time in London was only modestly successful, and in later years, he worked in Madrid, Vienna, Versailles, and Lisbon. Caffarelli’s worst enemy “was his own temperament.” He was notoriously touchy about his status and once violently quarrelled with a colleague. He challenged a librettist to a duel and spent time under house arrest and even in prison for assault. On occasion, he indulged in indecent gestures and mimicry of other singers, and was constantly late for concerts and rehearsals. Handel had a reputation for managing the tantrums of even the most difficult singers, and he certainly handled Caffarelli during the Faramondo run. The opera was scheduled for seven performances in January 1738 and one more on 16 May. Caffarelli got into a huff because it meant that he probably had to rehearse the work again. Not sure if his memory would serve him, Caffarelli “encouraged acquaintances not to attend.” Handel got his revenge however, as “throughout the performance, he played every note of Caffarelli’s part on the harpsichord, as one might have done for an inexperienced singer, just in case the great man forgot his lines.”

George Frideric Handel: Serse, “Ombra mai fu” (Franco Fagioli, counter-tenor; Il Pomo d’Oro)

Domenico Annibali, nicknamed “Domenichino”

Domenico Annibali (1705–1779) had an active international career under the stage name “Domenichino.” After appearances in Rome and Venice, Domenichino was engaged in 1729 for the Saxon court at Dresden. He created roles in the premieres of two Johann Adolf Hasse operas, including Cleofide (1731) and Cajo Fabricio (1734). Although he was under contract in Dresden, he was given frequent leave to take on outside engagements. As such, he sang in Rome and Vienna and made his London stage début as a member of Handel’s company at Covent Garden. Charles Burney wrote, “his abilities during his stay in England seem to have made no deep impression.” However, Annibali was said to have inherited the “best part of Senesino’s voice, with prodigious fine taste and good action.” He was certainly praised for his coloratura facility, although his acting was found to be somewhat wooden. While Annibali was performing in London, the Saxon court offered him an increased salary, and he returned to Dresden. He remained active until 1756 and left for his homeland in 1764 with an official pension and the title of “Kammermusikus.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Johann Adolf Hasse: Cleofide, “Cervo al bosco” (Dominique Visse, counter-tenor; Cappella Coloniensis; William Christie, cond.)