Critical mass is a concept used in nuclear physics, group dynamics, politics, public opinion, medicine, and technology. Differences between disciplines none withstanding, it “identifies the minimum amount (of something) required to start or maintain a venture.” In business, for example, critical mass is the point at which a growing company becomes self-sustaining, and no longer needs additional investment to remain economically viable. In nuclear physics, meanwhile it identifies the minimum mass of fissionable material that can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. In the world of sociology, critical mass is a “sufficient number of adopters of an innovation in a social system so that the rate of adoption becomes self-sustaining and creates further growth,” and in political circles it is commonly referred to as majority consensus. I think you get the point, but the question remains, is there something like critical mass in classical music?

Critical mass is a concept used in nuclear physics, group dynamics, politics, public opinion, medicine, and technology. Differences between disciplines none withstanding, it “identifies the minimum amount (of something) required to start or maintain a venture.” In business, for example, critical mass is the point at which a growing company becomes self-sustaining, and no longer needs additional investment to remain economically viable. In nuclear physics, meanwhile it identifies the minimum mass of fissionable material that can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. In the world of sociology, critical mass is a “sufficient number of adopters of an innovation in a social system so that the rate of adoption becomes self-sustaining and creates further growth,” and in political circles it is commonly referred to as majority consensus. I think you get the point, but the question remains, is there something like critical mass in classical music?

Antonin Dvořák certainly thought so, as he was hired by a wealthy American patron of classical music to establish a uniquely American school classical music composition. Dvořák, who had achieved a worldwide reputation as a composer utilizing nationalist musical elements and styles, unmistakably issued a clear challenge to American composers to find a distinctive American musical voice. He published his thoughts in an essay entitled “Music in America,” which appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in February 1895. “My own duty as a teacher is not so much to interpret Beethoven, Wagner or other masters of the past, but to give what encouragement I can to the young musicians of America…This nation must assert itself, especially in the art of music. When no large city is without its public opera house and concert hall and without its school of music and endowed orchestra, where native musicians can be heard and judged, then those who hitherto have had no opportunity to reveal their talent will come forth and compete with one another till a real genius emerges from their number, who will thoroughly represent this country.” Now that’s what I call an abundantly clear definition of critical mass in music!

Being America, with basically no homegrown history and tradition of classical music, Dvořák’s appeal was not entirely successful. Of course, what Dvořák essentially described was a European model of classical critical mass that had governed much of the continental musical discourse in the 19th century. Young and talented composer from all parts of the continent eagerly contributed compositions to an ever-increasing mass of musical works that eventually gave rise to the masterworks of classical music we still enjoy. And with the meteoric rise of the piano as the musical instrument par excellence, it was no surprise that the hottest battles were fought on the concert stage. While we are intimately familiar with the masterworks of the genre, the almost endless variety and diversity of works that actually made those masterworks possible have become mere footnotes in music history. And our little series titled “Unsung Concertos” is primarily concerned with those historical footnotes!

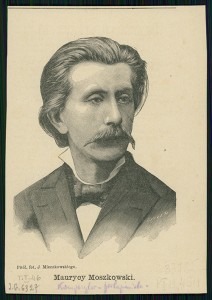

So, let’s get started with Moritz Moszkowski, a brilliant pianist who ended up teaching in Berlin and in Paris. Much admired by Franz Liszt, Moszkowski composed brilliant showpieces for the piano, among them two piano concertos. Ignacy Paderewski once famously wrote, “After Chopin, Moszkowski best understands how to write for the piano.” A number of his small but brilliant piano pieces are still used as encore pieces, but his larger works have not managed to stay in the repertory. His Op. 3 Concerto dates from 1874 but was only rediscovered in 2011 and first published in 2013. Exhibiting a sense of refined contrast and balance—not to mention a multitude of gorgeous melodies—Moszkowski wasn’t entirely happy with his effort. In response to a request for an autobiography, Moszkowski replied, “I should be happy to send you my piano concerto but for two reasons: first, it is worthless; second, it is most convenient for making my piano stool higher when I am engaged in studying better works.” I trust you agree that Moszkowski was badly mistaken in his self-assessment!

Moritz Moszkowski: Piano Concerto Op. 3

You May Also Like

- Moritz Moszkowski: Suite for 2 Violins and Piano, Op. 71 When Moritz Moszkowski died in April 1925, a prominent musical journal reported, “Moszkowski dead! So painful an announcement has not stricken the entire musical word since the deaths of Chopin, Rubinstein, and Liszt.

- Unsung Concertos

Joseph Leopold Eybler: Clarinet Concerto (1798) The comparatively late addition of the clarinet family to our modern catalogue of musical instruments at the turn of the 18th century immediately spawned countless generations of woodwind virtuosi. - Unsung Concertos

Nikolaus Kraft: Cello Concerto No. 1 (1815) Antonín Kraft was one of the earliest cello superstars! - Unsung Concertos

Sergei Bortkiewicz: Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 16 (1913) Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877-1952) described himself as a romantic and a melodist, and he had an emphatic aversion of what he called modern, atonal and cacophonous music.

More Anecdotes

- Bach Babies in Music

Regina Susanna Bach (1742-1809) Learn about Bach's youngest surviving child - Bach Babies in Music

Johanna Carolina Bach (1737-81) Discover how family and crisis intersected in Bach's world - Bach Babies in Music

Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) From Soho to the royal court: Johann Christian Bach's London success story - A Tour of Boston, 1924

Vernon Duke’s Homage to Boston Listen to pianist Scott Dunn bring this musical postcard to life