Let’s continue to explore more concertos for unique instruments.

Chen Gang: Butterfly Lovers Erhu Concerto

Monument to Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai

The legendary story of Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai, better known as the “Butterfly Lovers,” has long reverberated in traditional Chinese opera. Localized differences aside, this grievous love story doomed by rigid social conventions is rightfully considered an elemental part of China’s historical heritage. The narrative relates that Zhu disguises herself as a male student and meets Liang at school. They study together for three years, and when Liang finally discovers Zhu’s true identity, they fall in love. They are devoted to each other and want to stay together forever. However, Zhu’s parents have already arranged for her to marry another man. Liang is heartbroken when he hears the news, and his health gradually deteriorates. He becomes critically ill and dies afterwards. On the day of Zhu’s marriage, the wedding procession passes by Liang’s grave. Zhu throws herself into the grave to join Liang. Their spirits emerge in the form of a pair of butterflies and fly away together, never to be separated again.

For two students from the Shanghai Conservatory, this folk legend provided the basis for a work for violin and orchestra, aptly named The Butterfly Lovers Concerto. The skillful blending of models and techniques from the Western symphonic tradition with Chinese folk music and local instrumental/vocal techniques created a redolently musical symbolism that has easily become a modern Chinese classic. In today’s concert hall, it is not uncommon to hear this concerto played by Chinese instruments with the violin part performed on the erhu. This traditional Chinese two-stringed bowed instrument is widely popular in a variety of folk art. The instrument is composed of a sound box, a neck, two strings, two tuning pegs, and a bow. Erhus are commonly made from red sandalwood or mahogany, and a patch of snakeskin covers one side of the sound box. The erhu produces a captivating and unique sound, and although it has only two strings, “it can produce quite expressive music.”

Gabriel Prokofiev: Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra

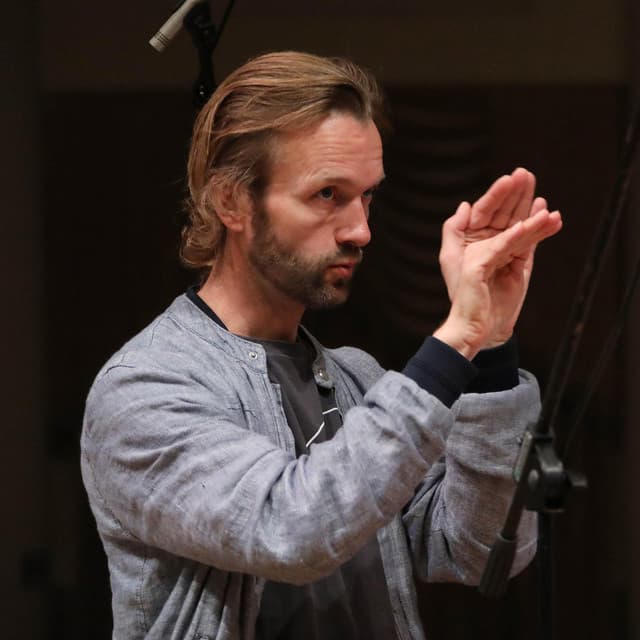

Gabriel Prokofiev

Contemporary composers are readily exploring new avenues when it comes to writing concertos. And one of the most recent, not to mention one of the most unusual, is Gabriel Prokofiev’s Concerto for Turntables. It all started in 2005 when a pianist and events producer approached Prokofiev with the idea of composing a concerto for DJ. “My immediate reaction was negative,” Prokofiev recalled. “It sounded too gimmicky to me, and I was concerned it would seem like another PR exercise to get classical music down with the kids.” In the end, Prokofiev changed his mind, fascinated with the idea that hip-hop culture had discovered that a DJ “can do so much more than just play records.” For Prokofiev, the turntable instrument “has somehow stayed within the world of hip-hop and dance, never venturing into the classical world, despite the incredible expressive potential it has.”

Turntable Concerto

The central inspiration for placing hip-hop music within the context of a concerto emerged from the turntable instrument itself. Prokofiev consulted DJ Yoda, who demonstrated the range of techniques on offer, including phasing and mixing. Scratching techniques, which, according to the composer, can be extremely expressive and musical, include “scribbling, planing, hydroplaning, the transformer, echoes, the crab and the baby.” For Prokofiev, the biggest challenge after composing the score was “how to notate the DJ part. I found that simplicity was the key, as DJs are not used to following scores. So I made a simple score that marks all the entries, the main rhythms and the sounds to use, but much of the details and ornamentation is open for improvisation and is discussed in rehearsals. This characteristic gives a nod to the early days of the concerto, when soloists were given more freedom to improvise. So, in one way, this new instrument is bringing the concerto form back to its roots.”

Gabriel Prokofiev: Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra No. 1 (Mr Switch, turntables; Ural Philharmonic Orchestra; Alexei Bogorad, cond.)

Peter Maxwell Davies: Piccolo Concerto

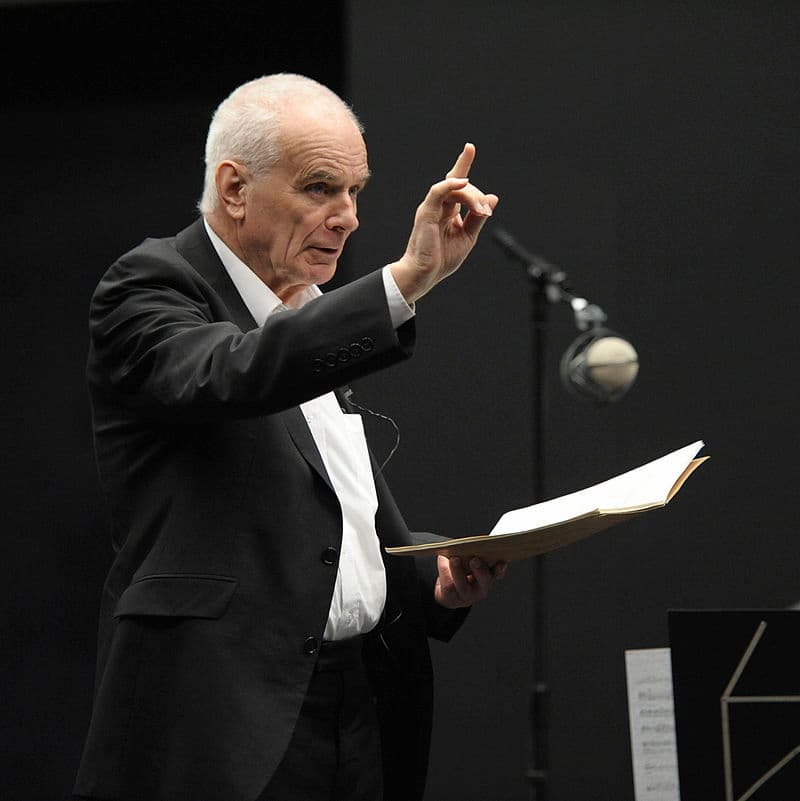

Peter Maxwell Davies

Scholars have suggested that the finest compositions by Sir Maxwell Davies (1934-2016) “have a depth of symbolism and historical reference rarely encountered elsewhere in contemporary music.” One of the foremost composers of our time, Davies has cultivated a number of styles, ranging “from the unbridled Expressionism of his music-theatre pieces of the late 1960s to the majestically unfolding landscapes of his later orchestral works.” His cycle of ten string quartets is hailed “as one of the most impressive musical statements of our time,” and his ability to communicate directly and powerfully also informs a number of witty light orchestral works. Craftsmanship is at the center of all his compositions, no matter the style or genre. His major dramatic works include two full-length ballets, works for the music theatre, and the operas Resurrection, The Lighthouse, The Doctor of Myddfai, and Taverner and Kommilitonen!

In 1986, the Strathclyde Regional Council, supported by the Scottish Arts Council, commissioned Maxwell Davies to write a work for instrumental soloist and small orchestra. The first concerto, for oboe and orchestra, appeared in 1986 and the tenth and last work, a concerto for orchestra, concluded the cycle of “Strathclyde Concertos” in 1996. In terms of composing concertos, however, Davies was just getting started. After completing his massive Piano Concerto, Davies turned his attention to the piccolo flute. Because of its high frequency and silvery sound, the piccolo is not generally thought of as a solo instrument. The Piccolo Concerto unfolds as a single continuous movement, and Davies supports the high-frequency soloist with well-balanced textures that include tuned percussion. This produces a “northern lights acoustical glow” around the soloist, particularly in the central section. This uneasy sense of otherworldliness is framed by lively and rhythmically uneven dances in the outer movements.

Peter Maxwell Davies: Piccolo Concerto (Stewart Mcllwham, piccolo; Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Peter Davies Maxwell, cond.)

Elena Kats-Chernin: The Witching Hour “Concerto for Eight Double Basses”

Elena Kats-Chernin

The composer and pianist Elena Kats-Chernin was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and musically trained in Moscow before moving to Australia in 1975. Graduating at the New South Wales Conservatory of Music in 1980, she furthered her studies with Helmut Lachenmann in Hanover, Germany. Remaining in Germany, she produced music for ballets and numerous soundtracks for theatre productions in Bremen, Bochum and Vienna. She returned to Sydney in 1994, and her music “often combines simple formulaic material with idiosyncratic textures. She works from an intuitive perspective, and important aspects of her works are concerned with an exploration of timbres and textures and a sense of the ridiculous.” Kats-Chernin writes abstract music but has a preference for working with narrative. “I get suddenly ignited by stories, but you know, it is a mystery how a character can make me write a certain kind of chord.”

Commissioned by the Australian World Orchestra in celebration of their fifth anniversary season in 2016, Kats-Chernin composed a Concerto for Eight Double Basses and Orchestra. Titled “The Witching Hour,” it is based on the famous Russian fairytale “Vassilissa the Beautiful.” In the first movement, “Spectres in the Forest,” Vassilissa is sent by her evil stepmother into the dark forest to ask the witch Baba Yaga for light. Vassilissa gets lost and is surrounded by delightful ghouls and spirits who scare her with exuberant and spooky dances. Vassilissa is renowned for her fair beauty, and her mother had previously given her a little wooden doll. In the second movement, “The Wooden Doll Awakens”, we find out that the doll actually has magical powers. Vassilissa and her father are struck by terrible grief in “Elegy,” as she remembers the death of her mother. In the concluding movement, “Vassilissa the Beautiful,” Baba Yaga challenges the girl with a series of tasks. If she cannot complete them, Vassilissa will be eaten. The doll helps Vassilissa to overcome all obstacles and the nasty witch. Kats-Chernin’s concerto not only presents exciting music but has visual potential as well. “Eight mighty double basses stand at the front of the orchestra,” the composer explains, “and these majestic, opulent and self-assured instruments have an incredible musical and emotional range.”

Elena Kats-Chernin: The Witching Hour “Concerto for Eight Double Basses” (Kees Boersma, double bass; Timothy Dunin, double bass; Alex Henery, double bass; Max McBride, double bass; Kirsty McCahon, double bass; Matthew McDonald, double bass; Robert Nairn, double bass; Caro Vigilante, double bass)

John Beck: Concerto for Timpani and Percussion Ensemble

John Beck

Let us conclude this little survey of unique concertos with a bang. And that’s why we feature the Concerto for Timpani and Percussion Ensemble by John Beck. As a performer, Beck has worked for the “President’s Own Marine Band,” and as Principle Percussionist with the Rochester Philharmonic. Highly successful as a teacher and educator, he joined the faculty at Eastman in 1959 and retired in 2008. Yet he continues to be active as Professor Emeritus of Percussion and teaches a class in “The History of Percussion.” As an internationally renowned clinician and performer, Beck has also been involved in events throughout the U.S. as well as in Brazil, Italy, Poland, Lithuania, Spain, Croatia and Russia. In addition, he has published articles in numerous journals and contributed entries to the Grove Dictionary of American Music and the World Book Encyclopedia.

Beck’s Concerto for Timpani and Percussion Ensemble is a large work for percussion ensemble supporting the soloist with both melodic and rhythmic instrumentation. The marimba, xylophone, vibraphone, bells, and chimes cover the melodic aspect. Rhythmic support comes from the snare drum, bass drum, tom-toms, wood block and bongos. Finally, we also find a gong, triangle, and brake drums. This eclectic ensemble fulfills various roles, “at times serving as a unison rhythmic voice, a composite structure of rhythm, a carrier of the melody, and even an ethereal background for the solo timpanist.” The work opens with a slow introduction that accelerates into a brief cadenza. Two distinct melodic sections are taken through a number of rhythmic changes, all leading up to an exciting concluding timpani cadenza. As clearly seen in this little series, the concerto possibilities are endless.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter