Tōru Takemitsu

As a composer, Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996) was essentially self-taught. In fact, as he freely admits, his first real teacher was the radio. During the post-war occupation of Japan, Takemitsu worked for the U.S. Armed Forces. He contracted tuberculosis and was hospitalized for a long time. Takemitsu took his illness as the opportunity to listen to as much Western music as possible, broadcast on American Forces Radio. His first mentor, according to Takemitsu, was Debussy, and a fellow composer introduced him to the music of Messiaen. His first publically performed work, the Lento in due movimenti for piano of 1950, was not well received. However, it already showcases what would eventually become an essential element of Takemitsu’s musical language. Modal melodies emerge from a chromatic background and regular meter is suspended. Always acutely sensitive to register and timbre, the opening “Adagio” sounds a rather ominous harmonic intricacy.

Tōru Takemitsu: Lento in due movimenti – I. Adagio (Kotaro Fukuma, piano)

“shakuhachi” (bamboo flute)

Once Takemitsu’s work had started to attract international attention, he began his first serious exploration of the traditional music of his native country. He had long shunned any and all associations with Japanese music, but a landmark experience in 1960 awakened his fascination with traditional music and “released him from his self-appointed position of enslavement to Western music.” Witnessing a performance of traditional Japanese puppet theatre—in addition to an encounter with John Cage—led him “to recognize the value of my own tradition.”

“biwa” (short-necked lute)

He began to compose pieces for non-Western instruments, such as the “biwa” (short-necked lute) and “shakuhachi” (bamboo flute), and in his writings he revealed his preoccupation with “Japaneseness” in music as well as East Asian aesthetics. Thus, as a composer Takemitsu positioned himself between two traditions. As he once remarked, “I would like to develop into two directions at once, as a Japanese in tradition and as a Westerner in innovation.” Composed in 1966, Eclipse for biwa and shakuhachi also required substantial notational innovation.

Tōru Takemitsu: Eclipse (Kinshi Tsuruta, biwa; Katsuya Yokoyama, shakuhachi)

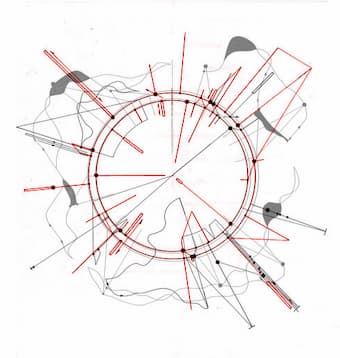

Takemitsu’s Corona graphic score

In Japanese language, “ma” is an everyday word meaning both space and time. It is an aesthetic concept that simultaneously expresses the past, space and time. However, it becomes meaningful only when filled with motion. Empty intervals of space and time are perceived as invitations, and in the products of Japanese art, “ma” becomes a means of inviting the audience as participants in the work of art. While the concept of “ma” stands at the center of Takemitsu’s aesthetic considerations, his musical language “gradually turned away from dense textures of chromatic clusters and sound masses towards a greater harmonic and timbral differentiation.” Widely spaced chords with little directional motion unfold in seemingly eternal motion. Takemitsu compared his Quatrain to a “picture scroll unrolled; the scene changes successively without a break. It emulates the relationship between a garden and a person walking through it.” In addition, Takemitsu’s choice of instruments is a clear reference to Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin de temps.

Tōru Takemitsu: Quatrain II (Tashi)

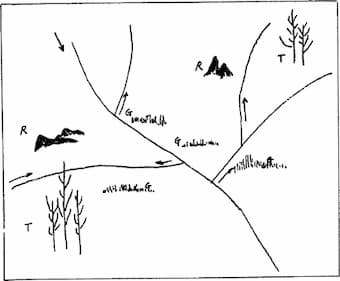

Takemitsu’s sketch showing the composition structure of his

Arc For Piano And Orchestra

The imagery of Japanese gardens from a multitude of perspectives, infused with all-pervasive numerology, inform many Takemitsu compositions. Equally prevalent in Takemitsu’s oeuvre is the image of water, dating back to his Water Music of 1960. During the late 1980s and 90s Takemitsu worked towards a stronger degree of tonal focus without ever really engaging diatonic tonalities. This increased linear orientation becomes “a narrative line intertwined with many threads,” and it led the composer into the domain of quotation. The Quotation of Dream from 1991 was inspired by a poem by Emily Dickinson. Takemitsu also integrates a number of passages from Debussy’s La mer. “While conspicuous and undisguised, the quotations create no sense of irony or stylistic rupture, Takemitsu’s orchestral textures sharing with Debussy’s a refinement, luminosity and remarkable transparency that caused him to be regarded, by the end of his life, as one of the finest orchestrators of the late 20th century.”

Tōru Takemitsu: Quotation of Dream (Paul Crossley, piano; Peter Serkin, piano; London Sinfonietta; Oliver Knussen, cond.)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter