Erik Satie: Gymnopédies & Gnossiennes

Anyone who has ever had the good fortune to look through a score of Parisian composer Erik Satie’s piano works will likely have come away amused, baffled, or even irritated. Satie’s performance directions take us into the realm of impossibility and absurdity and leave us wondering whether he intends to amuse, annoy, inspire, provoke, or alienate us – or all of the above, in equal measure.

Erik Satie © Atlas Press

In the Western classical tradition of music publishing, words between the staves are supposed to be sung or read out to the audience as the music is played or constitute a private instruction to the performer as to how a particular passage should be played. Erik Satie was, as far as we know, the first composer to break so thoroughly with this convention and include bizarre, poetic text that fulfilled neither of these functions. The relationship between these snippets and the music they appear alongside sparked debate amongst Satie’s contemporaries and has continually stumped and fascinated historians since the end of the 19th century.

In his famous Gnossiennes, Satie gives us a variety of strange prompts:

- “With the tip of your thought. Postulate within yourself. On the tongue.”

- “With surprise. Don’t go out. With great kindness.”

- “Alone for an instant. So that you obtain a hollow.”

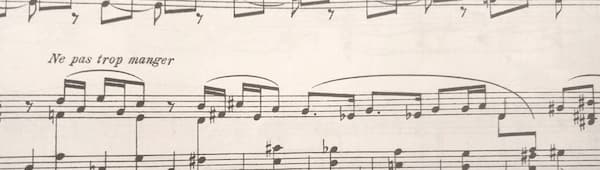

A Satie piano piece, where the pianist is asked “not to eat too much” (!)

Some of his prose can almost be seen as an intelligible artistic image or instruction, translatable into one’s pianistic interpretation, such as the evocation, “To ignore one’s own presence” within the piano piece Le Fils des étoiles. One can almost imagine, as the performer, trying to forget oneself in the moment of performing by becoming utterly absorbed in the musical phrase. However, as with much of Satie’s behaviours, an ironic facet is soon apparent upon reflection – an instruction to be less self-aware is only likely to make one more self-conscious!

Other score markings from Satie seem to be purely humorous. In Embryons desséchés, he uses the simile: “like a nightingale with a toothache.” In this respect, Satie’s music text resembled the avant-garde poetry of contemporaries such as Blaise Cendrars or Guillaume Apollinaire, with their delight in a stream of consciousness and streams of seemingly unrelated imagery.

Apollinaire’s Procession translated by Anne Hyde Greet 1965

What happens if we really give Satie’s writings due consideration? Perhaps Satie wasn’t simply providing us with amusement, detached irony, or nonsensical images with a poetic sensibility. Peter Dayan has argued that Satie’s texts serve as reminders not to be overly literal-minded about music or poetry: “music and poetry… help each other first to invite and then to defy interpretation.” Furthermore, Satie’s use of text seemed to actually be a fruitful compositional tool, as Caroline Potter’s examinations of his sketches and notebooks have shown that Satie’s writings helped him to generate further musical ideas and that sometimes, text came before music. Satie had effectively created a new kind of musical notation, and questions of music notation cut to the very heart of what we value and expect from music itself.

Sadly, those of Satie’s time were, by and large, not very generous in their interpretation of Satie’s music-poetic creations. Satie’s contemporary Amédée Ozenfant noted that Satie’s imaginative way with words proved a distraction, writing of occasions where the audience’s laughter at Satie’s amusing programme notes made his piano performances harder to hear in parlour settings. Even if he was respected musically, from the mid-1910s, his textual innovations led him to be seen by many as purely a “humorist” or a buffoon.

History, however, has been kind to Satie, and he has been lauded by many as a genius whose harmonic, gestural, and philosophical contributions to music were light-years ahead of his time.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter