When we think about the great composers, it’s easy to imagine them as super-geniuses isolated in their own little rarefied world.

But of course, the great composers were only human, living and working alongside other humans.

Almost all of the great composers had brilliant, fascinating women in their lives who were major parts of their inspiration and success.

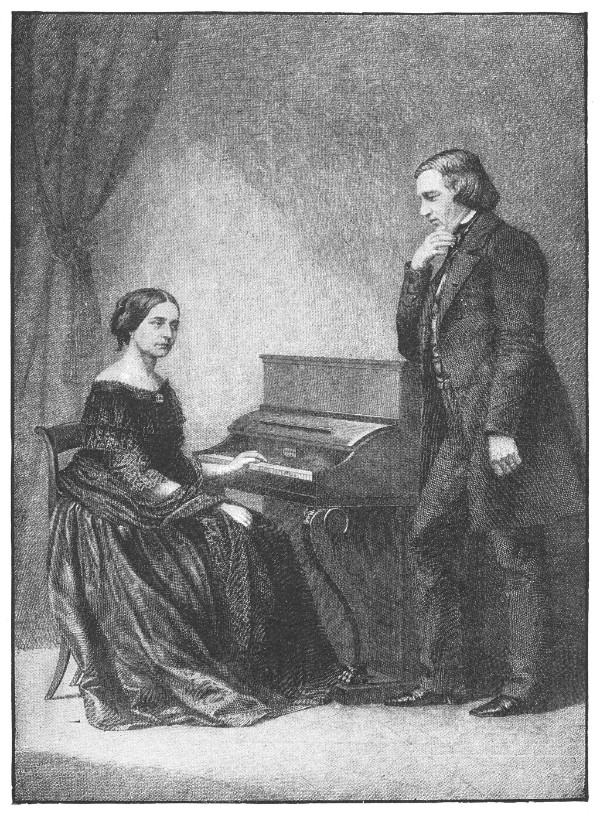

Portrait of Frédéric Chopin by Maria Wodzińska

Today, let’s take a closer look at some of the women who were important in Frédéric Chopin’s life:

Tekla Justyna Krzyżanowska

Tekla Justyna Krzyżanowska

Tekla Justyna Krzyżanowska was born in 1782 in the town of Długie in present-day central Poland.

Both of her parents came from a noble background. Her father worked for the wealthy Skarbek family. In fact, at one point he’d served as the administrator of one of their estates, but at the time of Justyna’s birth, he was leasing land from them in Długie.

Justyna started her working life as a healer in the adjacent town, but in her early twenties, she was hired by the Skarbeks as a housekeeper and nanny.

While in the Skarbeks’ employ, she met a tutor named Nicolas Chopin, and the two fell in love, with some matchmaking help from Mrs. Skarbeks. They were married in 1806 and would follow the Skarbeks as they moved between various homes in Poland.

In 1807, they had a daughter named Ludwika, and in 1810, a son named Frédéric.

The following year, Justyna accepted a position teaching French at the Warsaw Lycaeum. The family moved to Warsaw and stayed there.

They had two more children named Izabela and Emilia, took in boarders to supplement their income, and hosted many formative musical evenings at home.

Justyna taught her daughter Ludwika piano, and Ludwika, in turn, taught her brother Frédéric.

After he advanced beyond her knowledge, Justyna took over teaching him. But when he was only seven, his abilities outpaced even hers, and the family hired an outside teacher.

Frédéric ended up dying young and before Justyna, in 1849. In her old age, Justyna moved in with her daughter Izabela and her husband. She died in 1861.

Polonaise in g minor, Op Posth

Composed by Chopin, aged 7

Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz

Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz

Ludwika Chopin Jędrzejewicz was born in 1807. She was named after Countess Ludwika Skarbek, one of her parents’ employers.

Ludwika grew into a very capable, very industrious young woman. She learned piano from her mother and taught it to Frédéric.

Later, she studied music alongside her brother under teacher Wojciech Żywny, and was also a composer. Frédéric wrote to a friend in 1825, when Ludwika was just eighteen, that “Ludwika has composed a perfect mazurek, of a kind that Warsaw has not yet danced to.”

Polish nationalism and resistance against Russian oppression was a cause close to Ludwika’s heart. She worked with her younger sister Izabela with the Polish Ladies Benevolent Society. They even co-wrote a book together.

In 1830, when she was twenty-three and Frédéric twenty, he decided to leave for Paris to pursue his career. Their parting was bittersweet, but they kept in touch over the years.

When it became clear that Frédéric was nearing his final days, Ludwika traveled to Paris to be with him. The attention she gave to her beloved brother angered her husband, and their relationship deteriorated. She spent months in Paris, working to square away Frédéric’s manuscripts and securing his legacy.

Per his wishes, she traveled back to Poland with her brother’s heart so it could be buried there. To avoid questions, she stored it in a cognac bottle and tucked it under her coat so no border agents would ask any questions.

Playing Chopin’s Last Piece in Chopin’s Last Room

Maria Wodzińska

Maria Wodzińska

Maria Wodzińska was born in Warsaw to an aristocratic family in 1819. When she was thirteen, her family moved to Geneva. She studied piano with John Field, as well as art. With her talent and charms, she quickly became the bright light of the household.

When she was sixteen, her family moved to Dresden. While there, the twenty-five-year-old Frédéric fell into the Wodzińskas’ social circle and fell in love with her.

He gave her daily piano lessons, and she drew his portrait, and the result is one of the best likenesses we have of him.

In 1836, she and Frédéric became engaged. However, for reasons that aren’t totally clear, they ultimately split up in 1837.

In the summer of 1841, when she was twenty-two, she married Józef Skarbek, the son of Frédéric’s godfather. Unfortunately, that marriage ended in divorce soon after.

In 1848, the year before Chopin’s death, she married for a second time, this time to a man named Władysław Orpiszewski. She had a son with him, but the son died at the age of four, and she was widowed in 1881.

Waltz in A-Flat, Op. 69, No 1 “L’ Adieu”

George Sand

George Sand

George Sand was born Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin in 1804 in Nantes, France, to an important French family. When she was eighteen, she married a man named Casimir Dudevant, and they had two children together in 1823 and 1828.

However, Mrs. Dudevant tired of domestic life quickly. In 1831, she chose to separate from Dudevant and pursue short-term relationships with a wide variety of important and intellectual men – and at least one woman.

In 1831, she began writing with one of her boyfriends, a writer named Jules Sandeau. She soon started writing by herself and chose to use the pseudonym George Sand. Almost immediately, she became the most famous author in Europe.

In 1836, around the time of his ill-fated romance with Maria Wodzińska, Chopin met Sand at a party thrown by Franz Liszt’s girlfriend, Countess d’Agoult. He was initially taken aback by her scandalous presentation of gender, exclaiming, “What an unattractive person la Sand is. Is she really a woman?”

By 1838, Sand sent out feelers in her social circle to find out if the relationship with Wodzińska was over, which it was. That year the two became romantic partners.

Sand wrote of their connection, “I must say I was confused and amazed at the effect this little creature had on me… I have still not recovered from my astonishment, and if I were a proud person, I should be feeling humiliated at having been carried away…”

During the ten years he was with Sand, Chopin wrote many of the most memorable works of his career, especially during the summer, when they would stay together at the picturesque country home in Nantes that she’d inherited.

Over the 1840s, his health deteriorated and he and Sand drifted apart romantically. He didn’t feel as strongly about politics as she did, and Chopin started taking her daughter’s side in family quarrels. Finally, the two broke up for good. Chopin would die in 1849.

That year, Sand began a relationship with engraver Alexandre Manceau. The two stayed partners until he died fifteen years later.

She spent her last years writing for the theater and serving as a healer after taking anatomy lessons and studying herbs. She also continued writing, sharing her political views in a variety of tracts.

After she died in 1871, Victor Hugo said at her funeral, “George Sand was an idea. She has a unique place in our age. Others are great men…she was a great woman.”

Prelude in D flat major Op. 28 No. 15 “Raindrop”

Jane Stirling

Jane Stirling

Jane Stirling was born to a wealthy family in Scotland in 1804. By the time she was sixteen, she was an orphan – and an heiress. Her widowed older sister Katherine agreed to take care of her, and the two women set off for Paris.

Sometime around 1842, she met Frédéric Chopin and began studying piano with him. He was impressed by her and told her, “One day you’ll play very, very well.” In 1844, he dedicated the two nocturnes in his op. 55 to her.

Stirling gradually became more and more indispensable to Chopin, eventually becoming his secretary and even concert agent.

When he ran into health problems, and financial problems at the end of his life, she suggested a British tour, which he spent the summer of 1848 carrying out. Ultimately the tour was not a great financial success, and so Stirling discreetly paid his debts.

After his death in the autumn of 1849, she footed the bill for his funeral and his sister Ludwika’s transportation from Warsaw. She also bought his estate so that it could be cataloged and preserved.

She spent the rest of her life advocating for Chopin’s work and memory. She died in 1859 of an ovarian cyst. Stirling left much of Chopin’s estate to his mother, bringing this list of extraordinary women full circle!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter