The Welsh composer, Alun Hoddinott (1929–2008), made Cardiff, Wales, the basis for his work, first as an undergraduate at the University, then as Lecturer, and finally Professor and Head of Music (1949–1987). One of the important legacies he left was the Cardiff Festival of 20th-century music, which he established in 1968 and led for the next 22 years. When he retired at age 60, he turned from university administrative duties to the joys of composition. He had a work list that included 10 symphonies, 6 operas, 13 piano sonatas, 5 string quartets, 6 violin sonatas, several large-scale choral works, including the oratorio The Tree of Life (1971), Sinfonia Fidei (1977), and the cantata The Legend of St. Julian (1987)) and over 20 concerto-like scores for virtually every traditional instrument, including the cello concerto Noctis Equi for Mstislav Rostropovich in 1989.

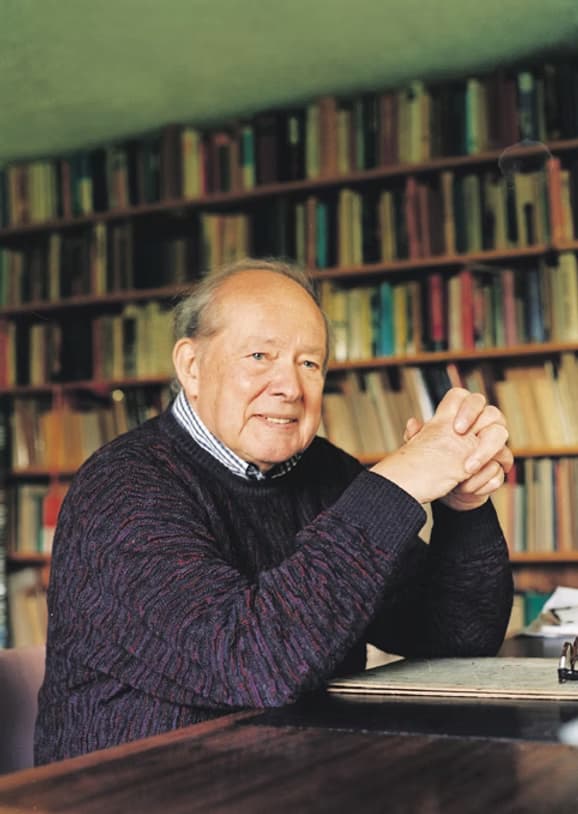

Alun Hoddinott (Photo by Chris Stock)

Alun Hoddinott and Benjamin Britten in Aldeburgh

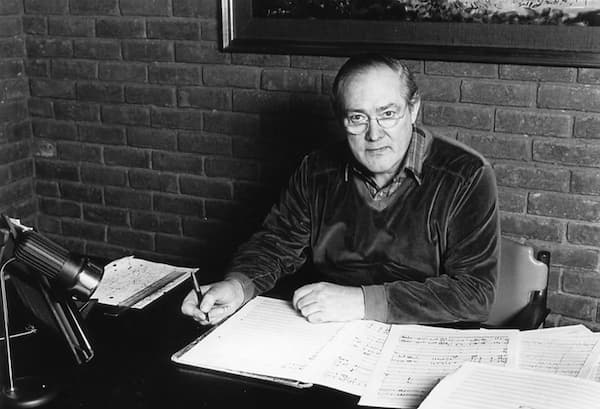

Alun Hoddinott at work

He was a child violinist and, later, became a founder of the National Youth Orchestra of Wales, where he played the viola. By the time he was awarded his Doctorate in Music in 1960, he was considered one of the leading British composers of his generation. The effect of the Cardiff Festival of 20th Century Music was to make South Wales a center for the latest music. He brought in the world’s leading composers, including Benjamin Britten and Olivier Messiaen, to the area.

As a composer, he had his works performed and broadcast while he was still a student, including his Clarinet Concerto, Op. 3. Performances at international festivals brought him to the world’s attention. He started attending the Cheltenham Festival beginning in 1947; this brought him into collegial contact with the leading composers of the day, including Ralph Vaughan Williams, Ernest Moeran, Benjamin Britten, Michael Tippett, Humphrey Searle, and Alan Rawsthorne. Rawsthorne in particular was an important influence on Hoddinott’s work.

As a composer, Hoddinott did not start from the same basic instrument as other composers, the piano. His first instrument was the violin, and so he saw a closer affinity to the Italian side of music rather than the Austro-Germanic side that the pianists looked to for models. His early work has more to do with form and structure than moving towards a goal. His works can be full of a densely chromatic lyricism, with ‘bristling rhythmic energy’. Although the serialism of the second Viennese school was all around him, he adopted serialism but did not abandon tonality.

By the 1960s, he was working with a broad and sophisticated orchestral palette, and, gradually, on the creation of works based on visual or poetic images. A work such as Lanterne des morts, Op. 105, No. 2 (1981), refers to a large, bee-hive–shaped structure found in France. At dusk, a lantern would be hoisted inside.

Lanterne des mortes (Village of Sarlat in the Département of Dordogne/France) (Photo by Manfred Heyde)

The original use of these hollow towers is unknown, but it’s thought to be a funeral beacon to be kept alight near tombs. At first, candles were used, then these stone towers stood in their stead. Whether they were to protect the living from the spirits of darkness or to illuminate the funerary ceremonies is unknown, but they eventually became reminders of the journey between the earthly light and heavenly light. In France, these generally date from the 12th century and are mostly located in what would have been the Duchy of Aquitaine.

In his notes about lanterne in Sarlat, Hoddinott notes two legends: ‘…it commemorates the miracle of healing with bread performed on the site in 1147 by Saint Bernard, and it is believed that the souls of those placed inside are transformed to white doves which fly away through the windows’.

In creating a work about the lanterne of Sarlat, Hoddinott has made an atmospheric and powerful world.

Alun Hoddinott: Lanternes des morts, Op. 105, No. 2 (BBC National Orchestra of Wales; Bryden Thomson, cond.)

He also started writing operas in the 1970s, some for the stage (The Beach of Falesá (1974)) and others for television (The Magician (1976) and The Rajah’s Diamond (1979)). Three operas were done with Myfanwy Piper, who had previously been working with Benjamin Britten until his ill-health made it impossible. One was The Rajah’s Diamond, mentioned above, based on a story by R.L. Steventon, and the last The Trumpet Major, based on a story by Thomas Hardy. Their first opera was for children, What the old man does is always right, based on a H.C. Andersen story.

As a Welsh composer, Hoddinott developed music for the local repertoire, whether a brass band or a Welsh choir. He wrote Christmas carols to Welsh texts,

Alun Hoddinott: Fendigaid Nos (Wondrous Night), Op. 25, No. 2 (BBC Welsh Chorus; John Hugh Thomas, cond.)

Welsh nursery songs for brass,

Alun Hoddinott: Quodlibet on Welsh Nursery Tunes (version for brass quintet) – I. Allegretto (Fine Arts Brass Ensemble)

and song cycles based on Welsh stories, set in Welsh and English.

Alun Hoddinott: 4 Welsh Songs, Op. 38, No. 3 (version for voice and piano) – No. 1. Cysga di, fy mhlentyn tlws (Rebecca Evans, soprano; Andrew Matthews-Owen, piano)

His first song cycle, 5 Landscapes, was done with the Welsh writer Emyr Humphreys (b. 1919). He wrote this cycle following the production of his first opera, The Beach at Falesá, which seems to have been the start of his fascination with solo song. Humphreys was living on the Isle of Anglesey, and so the poetry is full of the geography and topography, the natural and man-made, and the landscapes and seascapes that surrounded them.

Alun Hoddinott: 5 Landscapes: Ynys Mon (Isle of Anglesey), Op. 87 – No. 1. Mynydd Bodafon: Andante (Nicky Spence, tenor; Andrew Matthews-Owen, piano)

A work such as his Investiture Dances (1969) brings together a Welsh temperament with a brilliant orchestration and rhythm that could only be Hoddinott’s. The work was written for the investiture of Prince Charles as Prince of Wales in July 1969, a day of high ceremony and high drama because of opposition to the crowning.

The Investiture of Prince Charles, 1969

Alun Hoddinott: Investiture Dances, Op. 66 – I. Allegro (National Youth Orchestra of Wales; Owain Arwel Hughes, cond.)

After a long and productive career that made him the focal point for music in Wales, Hoddinott wrote his last work, a symphonic work entitled Taliesin, named for the Welsh bard of the 6th century. It was commissioned by the Swansea Festival of Music and Arts and given its premiere at Brangwyn Hall, Swansea, on 10 October 2009 by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, conducted by Francois-Xavier Roth.

Alun Hoddinott “Taliesin” for symphony orchestra

In discovering the world of Alun Hoddinott, you’re firmly in the 20th century, but at the same time, the Celtic world is looking over your shoulder. There’s an inherent melancholy in Taliesin, and this can be found in his other music. But, at the same time, he’s among the best and most talented of modern composers. You may not have heard of him, but now you should make sure to remember his name and seek out his music.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Great to see this excellent feature on Hoddinott, whose music was very successful in his lifetime but is not being performed nearly enough since he passed away. I hope this article prompts listeners to discover his music, especially in works like Lanternes des Morts, which is a great inclusion in the feature. Thank you.

Hoddinott was a great figure.

Also much neglected is William Mathias.

They were both great composers.

I wish more musicians would take up their music.