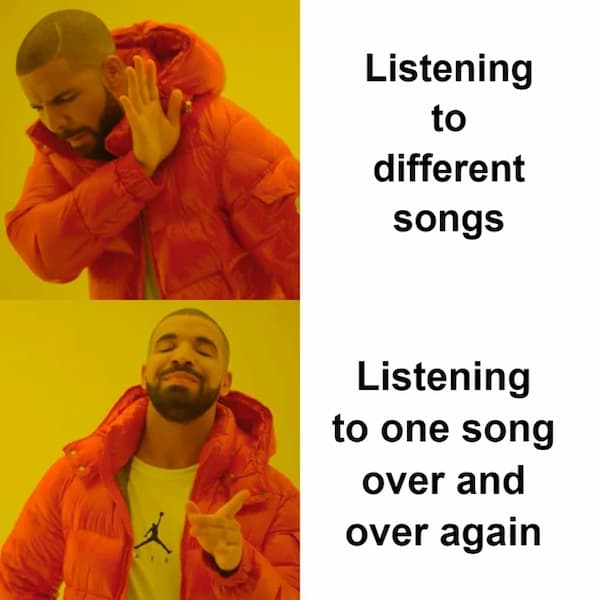

In an article for KQED, Jonathan Curiel coins the term “musical repeatism” to describe the phenomenon of wanting to listen to a piece of music over and over and over. In Spotify’s 2022 edition of Wrapped – the data-driven and playful infographic slideshow delivered to users about their listening habits over the course of the year – one of the musical personalities available was the “Replayer: you stick with the songs you like, by the artists you like.” Musical repeatism is a real phenomenon.

© Siddharth Bhogra/Unsplash

We live in the age of Spotify and Apple Music; of noise-cancelling headphones and private playlists. People can now queue their favourite songs ad infinitum. For some of the internet’s collective favourite tracks, there exist hours-long looped Youtube videos to make musical repeatism even more fuss-free. As Curiel notes, gone are the days of belligerently pleading with the bar pianist for just one more rendition of your favourite tune, as we see Humphrey Bogart do in the cinematic classic Casablanca. None of us has to plead anymore to satisfy our musical repeatism. We don’t need to book tickets to the opera or to a concert, learn or sing a tune for ourselves, get up to manually rewind a tape, or reposition the record player’s fickle needle to just the right groove. In the 21st century, we can live inside a piece of music in a way that previously just wasn’t possible.

For Curiel, the altered state of “living” inside a song is precisely the allure of repeatism. He highlights the “trance-like” mode that it allows, often quite useful for creatives who might need help in breaking onto an intimidatingly blank page, canvas, or stave. As professor Elizabeth Margulis writes in On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind, repetition has a neat effect of “fostering an intimate connection to the music while bypassing conceptual cognition… allowing the sound to seem ‘lived’ rather than ‘perceived’.” In this way, musical repeatism could be functionally similar to meditation, yoga, or even mind-altering drugs – a tool used to unlock creativity, focus, and presence. In my own life, musical repeatism has been very useful: a playlist of calm music featuring artists as varied as Sufjan Stevens, John Sheppard, John Dowland, and the quieter Radiohead ballads has been my enabling soundtrack for hours of studying and writing, slipping me into an alternate universe where writer’s block is merely a thing of myth. The playlist is just under three hours long, and by a conservative estimate, has accompanied thousands of hours of work.

John Dowland: Lachrimae, “Seaven Teares” – I. Lachrimae Antiquae (Nigel North, lute; Les Voix Humaines)

However, I suspect that much musical repeatism happens for reasons other than mindfulness and allowing workflow or “deep” thought. Mental illness is one of the leading causes of the global health burden, with depression and anxiety as leading contributors, according to a study published in The Lancet. With this in mind, musical repeatism might constitute an act of creating for oneself a sort of “musical cocoon” – a wall of stimulation and comfort through which distressing thoughts, feelings, or news of global disaster or conflict cannot emerge. In the same arena as white noise or the rapidly growing world of ASMR – parasocial videos intended to calm the viewer through relaxing sounds and attention – musical repeatism may be just another tool in an arsenal of technological self-medication. Nonetheless, such a strategy might be nothing to sneer at when used in tandem with structural or professional help: a survey of studies from NeuroLaunch has shown that music can rapidly instigate and reinforce emotions. For individuals seeking mood regulation, sticking an upbeat tune on repeat might be an effective and accessible form of music therapy, acting quickly on both body and mind.

Even with these potentially beneficial aspects identified, a feeling lingers that musical repeatism might be something to be ashamed of. I can think of no real instances where musical repeatism is sanctioned in group contexts. Old standbys and tunes (think: Sweet Caroline, Mr Brightside) are certainly tolerated time and time again, even evoking spontaneous upwellings of warmth and nostalgia, but never in a repeatist fashion where they are “on loop.” Stick one song on repeat at any social gathering and you will quickly find yourself pretty unpopular; programme a concert with only one work on repeat and watch the growing disgruntlement of most of those in attendance. On the individual scale, admitting to listening to one piece of music for hours on end might lead your interlocutor to consider you bizarre – or neurodivergent, if a little more sensitive-minded.

Part of the problem is our own relationship to our listening habits. Many of us feel that our Spotify activity is an intensely private thing, and that to poke or prod into another’s habits would be tantamount to investigating their laundry. Phones are such personal appendages, like little second brains inhabiting our hands and pockets. As such, listening history can become a deeply intimate matter. In conversation with musicians I’ve discovered a dizzying array of listening attitudes and ethics, the most severe stance consisting of a complete refusal to repeat songs in favour of only listening to albums in their entirety – often with singular focus and attention, out of a kind of reverence for the artist, or desire for a particular kind of listening experience. The music libraries we curate – the songs we save, like or download, the playlists we make – constitute a kind of unique musical fingerprint. It just so happens that for many of us, that fingerprint includes musical repeatism – a fact which may bring with it a certain degree of embarrassment.

As part of the research for this article, I spoke to avowed musical repeatist “Gage,” who is part of a community of those who track their own repeatism. Gage has listened to a particular track by American rock band The Fray seven hundred and forty-four consecutive times over the past five days. For Gage repeatism is a multi-layered process, where he might discover a musical sound by coincidence, become drawn in initially by feelings of nostalgia or the general atmosphere, and subsequently focus on different sonic aspects of the work on each listen, hearing the work in an entirely fresh way each time. Beautifully, comfort also plays a strong role. Of his current repeating song, Gage says: “it feels like a safe place… a warm blanket on a cold Saturday morning. I never want to leave.”

Stay tuned for part two, in which we dive even deeper into this strange and fascinating aspect of music-listening…

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter