Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) first encountered the Danube in March 1923. On a visit to Bratislava, Slovakia, he saw the river and decided to write a Slavic symphonic poem about it. He regarded the river as Slavic since it passed through four Slav states.

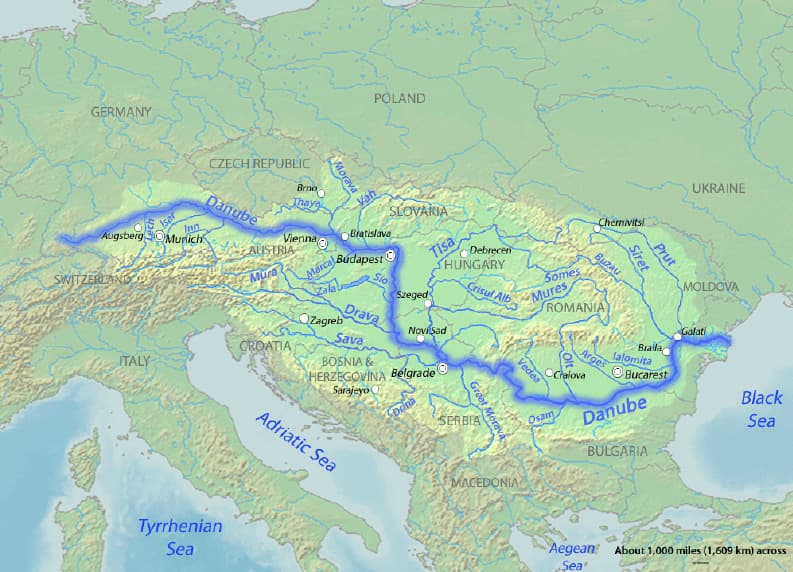

The Danube River’s route from Germany to the sea

He used Smetana’s earlier Vltava (The Moldau) as a model, a symphonic poem that strings together episodes from Czech history as we travel along the river from its beginnings to the sea. What Janáček chose to do, however, was to imagine the Danube as a woman, full of passion and with her own instincts. Janáček created the mythical link between women’s destinies and water.

Leoš Janáček in 1923 (Moravian Museum)

“Pale green waves of the Danube! There are so many of you and one followed by another. You remain interlocked in a continuous flow. You surprise yourselves where you ended up – on the Czech shores! Look back downstream, and you will have an impression of what you have left behind in your haste. It pleases you here. Here, I will rest with my symphony.” In this manner, Leoš Janáček described the idea behind The Danube.

Janáček had already finished a work with a strong river component, his opera Káťa Kabanová, in which his heroine ends her dishonour by throwing herself into the Volga River.

The Danube at the Great Kaza Gorge, 2018 (photo by Ted McGrath)

When Janáček died in 1928, The Danube was complete. He left sketches for four movements of what might have become a five-movement symphonic poem. Janáček’s student, Osvald Chlubna, made the first arrangement from the sketches, and a later arrangement was made by Leoš Faltus and Milan Štědroň, using the original orchestrated sketches.

Unlike most symphonic poems, this has a vocal part, sometimes setting poetry and other times a vocalise. The vocal is sometimes omitted in performance.

The first movement is based on the poem Lola by Alexander Insarov (pseudonym of Sonja Špálová), which tells the story of Lola, a prostitute who requests and receives her heart’s desire and lives a life of pleasure and happiness only to end destitute, cold, and hungry, not wanted by anyone. Janáček added his own ending to the poem to tie Lola to the river, where she takes her life; Janáček’s notation ‘she jumps into the Danube’ is not in the original poem. The movement is full of sound painting, such as the wave-like figures that evoke the river.

Leoš Janáček: Danube, JW IX/7 (arr. by L. Faltus and M. Štědroň) – I. Andante (Jana Valaskova, soprano; Zdenek Husek, viola; Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra; Libor Pešek, cond.)

The second movement uses another poem also associated with the river, The Drowned Girl by Pavla Křižková. A young girl, observed bathing by a boy she doesn’t know, is filled with shame and throws herself in the river to drown. The ‘tremolo of the four timpani’ brings the drowning bather to mind – a melancholic oboe with a descending figure reinforces the percussion melodically.

Leoš Janáček: Danube, JW IX/7 (arr. by L. Faltus and M. Štědroň) – II. Adagio (Jana Valaskova, soprano; Zdenek Husek, viola; Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra; Libor Pešek, cond.)

The third movement, which has an untexted vocalise, is intended to represent the city of Vienna. The singer mainly sings in parallel with a solo oboe but also with other instruments, including the viola d’amore, which for Janáček was the ‘voice of love’.

Leoš Janáček: Danube, JW IX/7 (arr. by L. Faltus and M. Štědroň) – III. Allegro (Jana Valaskova, soprano; Zdenek Husek, viola; Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra; Libor Pešek, cond.)

The final movement returns some of the melodic themes of the first movement.

Leoš Janáček: Danube, JW IX/7 (arr. by L. Faltus and M. Štědroň) – IV. Vivo (Jana Valaskova, soprano; Zdenek Husek, viola; Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra; Libor Pešek, cond.)

Janáček doesn’t take us on a pleasant tour down the river as Smetana does in the Vltava, but gives us a ‘fateful link between the destiny of women, water and death’, a very different concept.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter