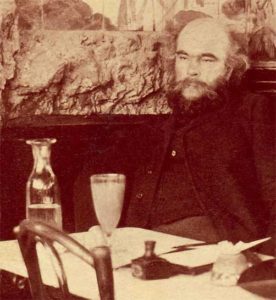

Paul Verlaine

While sitting in his prison cell in Mons city jail, Verlaine drew sketches and composed what many literary critics consider to be his finest poetry. Incarcerated for shooting his fellow poet and lover Arthur Rimbaud, his time in jail isolated him from the Parisian cafes, the beer, and the absinthe that had destroyed his health. The poet sensed that his time away from his escapades in Paris probably had saved his life. He wrote, “I once lived in the best of castles. In the finest land of white water and hills, four towers rose up from its four-winged front. And one was my residence for long, long days…”

The gun that Verlaine used to shoot Rimbaud

Verlaine converted to Roman Catholicism in the summer of 1874, after his wife had obtained a separation. When he left prison in January 1875, he tried a Trappist retreat and then hurried to Stuttgart to meet Rimbaud, who apparently repulsed him with violence. During this period in his life he penned most of the poems in Sagesse, poetical expressions of simple Catholic Christianity as well as of his emotional odyssey.

Déodat de Séverac: Le ciel est, par-dessus le toit (Carolyn Sampson, soprano; Joseph Middleton, piano)

The beauty of Verlaine’s language appealed to a wide range of French tastes, notably to composers both from the Schola Cantorum and from its rival, the Paris Conservatoire. The Schola Cantorum was severely criticized for encouraging a rather dry academicism, which allowed Déodat de Séverac (1872-1921) to exercise his musical imagination.

Beauty of women, their frailty, and those pale hands

Which often do good yet can bring all suffering.

And those eyes where of the creature nothing

Is left but enough to say enough to man’s demands.

And forever, the maternal sleeper’s call,

Even when it lies, that voice! The dawn

Cry, when soft vespers are sung, signal new-born

Or sweet sob that dies in the folds of a shawl! …

Harshness of man! Vile leaden life here below!

Ah! Let something at least, far from kisses and blows,

Let something survive for a moment on the slope,

Something the childlike subtle heart contains,

Goodness, respect! For dying what can we hope

To take with us, and truly, what when death comes remains?

Mons city jail

Claude Debussy composed his Ariettes oubliées mostly in Rome in 1886. Among the six ariettes is also a setting from Sagesse where subtlety, nuance, rhythm and tone color converge to create a mature compositional style. It set the tone for all of Debussy’s future vocal compositions, particularly in attention to poetic detail.

Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées – No. 4. Chevaux de bois (Lorna Windsor, soprano; Antonio Ballista, piano)

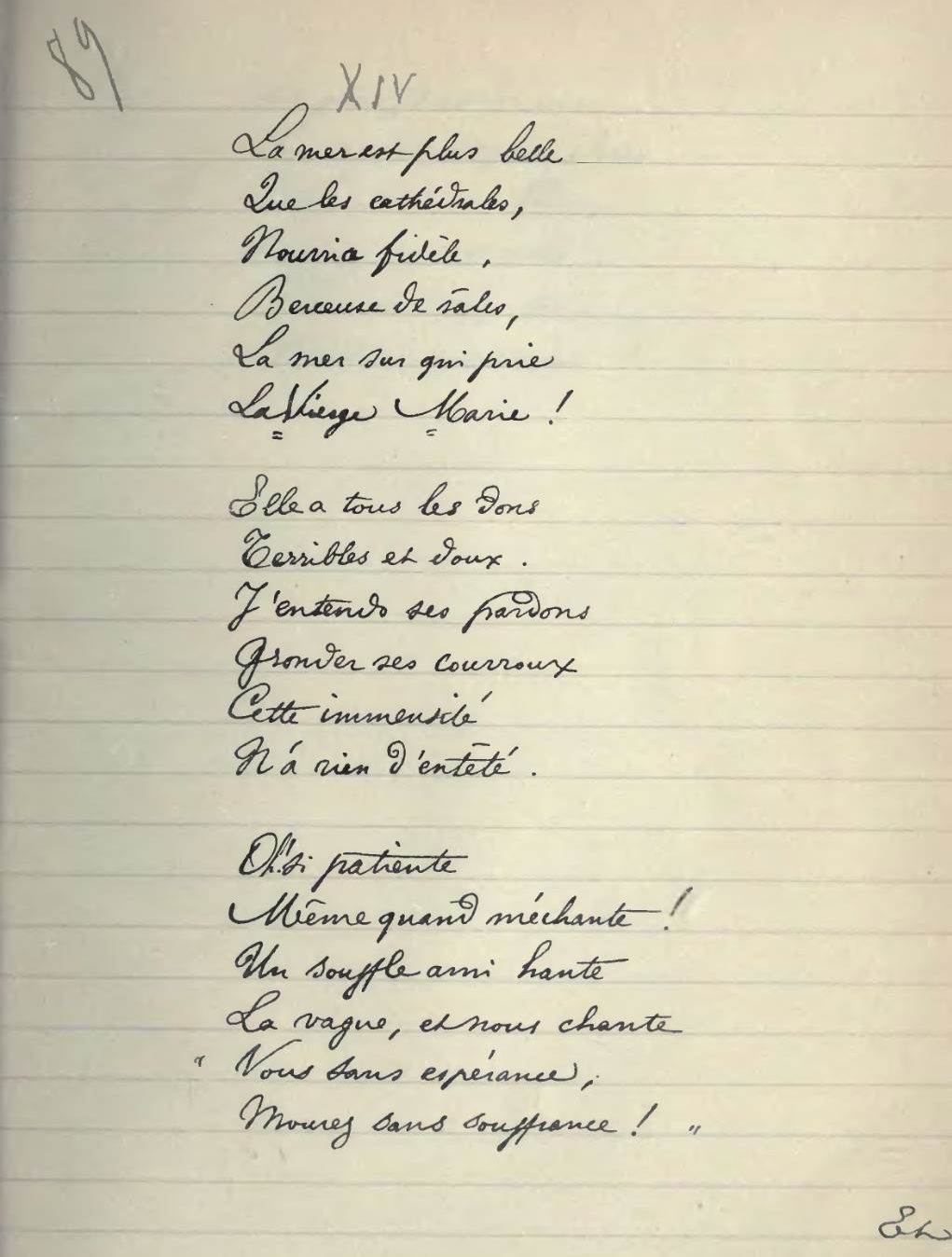

Verlaine’s Sagesse

Theodor Adorno described the music of Benjamin Britten with the following harsh words. “A taste for bad taste, a simplicity founded in ignorance, immaturity that fancies itself clear minded, and a lack of technical capacity.” Others, like Leonard Bernstein “became aware of something very dark.” Musical orientation and life choices have left its marks on Britten the person and on Britten the composer. It has, however, never been in doubt that Britten was a prodigious musical talent. He composed his Quatre chansons françaises, based on poems by Victor Hugo and Paul Verlaine at the age of 15. Although the composition was finished in 1928, the first performance was posthumously given only in 1980. The songs are dedicated by Britten to his parents for their 27th wedding anniversary, and one senses the musical influence of Debussy, Ravel and Bridge. There is also a sense that these juvenilia anticipate the works by the mature composer, as an operatic nature informs the solo oboe in Sagesse.

Benjamin Britten: Quatre Chansons Françaises – No. 2. Sagesse (Christiane Karg, soprano; Bamberg Symphony Orchestra; David Afkham, cond.)

Paul Verlaine, 1893

A critic wrote, Charles Tournemire “is a composer who serves music with all the fervor, passion, disinterest, the magnificent scorn of randomness and the tranquil temerity of the mystics. In his eyes shining with faith, in a smile that expresses so willingly rapture and ecstasy, one can read a divine awareness of total artistic diplomacy. Music is in him a boiling spring… and he practices at the extreme of contempt for commercial acumen.”

Tournemire’s deeply serious, religious, mystical mélodies are beautifully encoded in an 18-minute dialogue between God and a tormented soul to poems by Verlaine.

My God said to me: My son, you must love me. You see

My pierced side, my heart which shines and bleeds.

And my injured feet that Madeleine bathers

With tears, and my arms dolourous under the weight.

Of your sins, and my hands! And you see the cross,

You see the nails, the gall, the sponge, and all show you

The lack of love, in this world where the flesh reigns,

For my Body and Blood, my words and my voice.

Have I not loved you until my own death,

O my brother in my Father, O my son in the Spirit,

And have I not suffered, as was written?

Have I not sobbed your deepest anguish

And have I not sweated the sweat of your nights,

Pitiful friend who seeks me where I am?

Charles Tournemire: Sagesse, Op. 34 (Michael Bundy, baritone; Helen Crayford, piano)