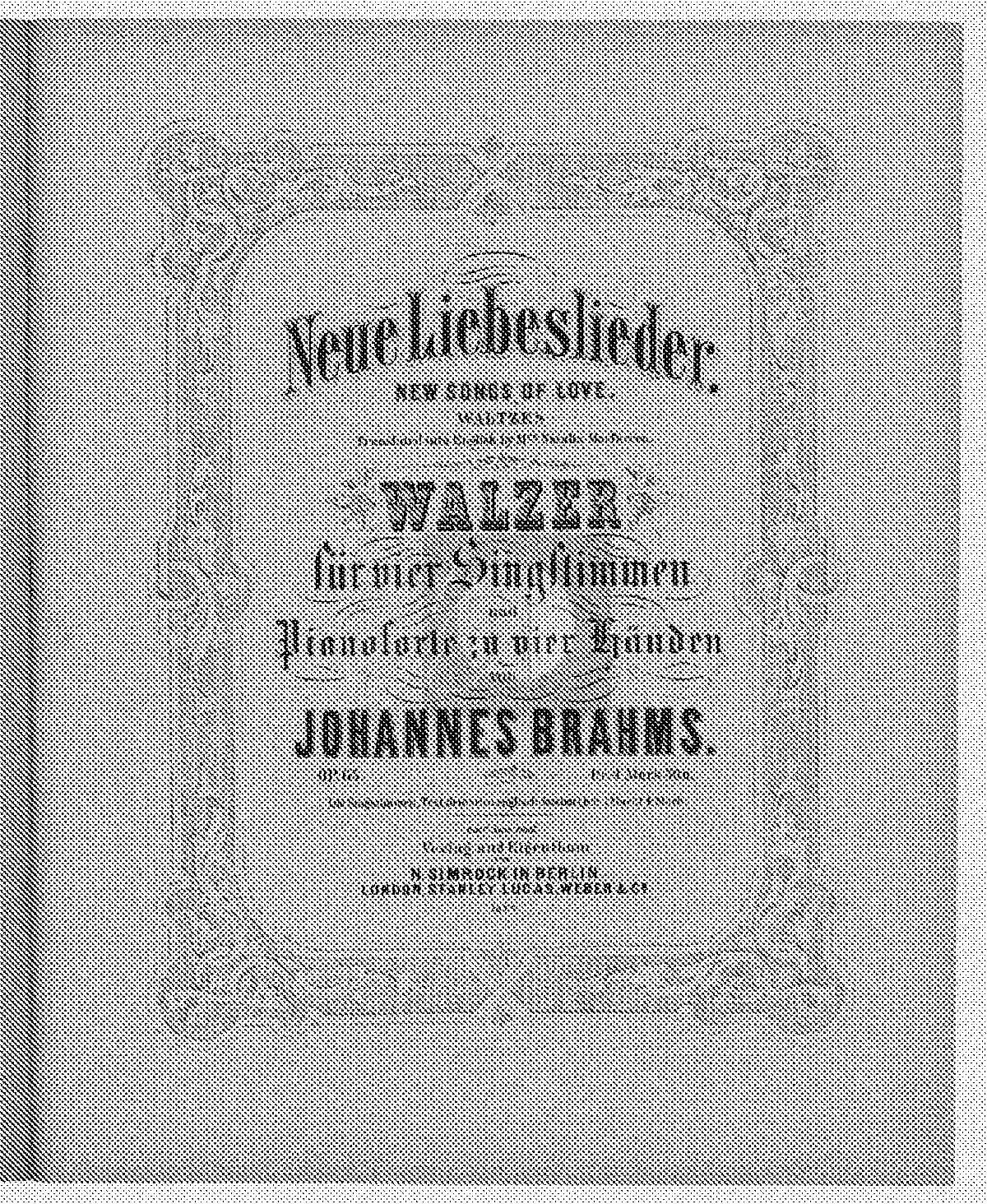

The Liebeslieder Waltzes Op. 52 had been a tremendous financial success for Johannes Brahms and his publisher. These compositions had perfectly capitalized on two musical trends of the mid-19th century. A popular love for dances to be played by piano duet, that is one piano and two players, and vocal music on the subject of love. In addition, the pieces were light and unpretentious, specifically designed for the enjoyment of talented amateurs. By popular demand, Brahms produced a new set five years later, composed in the spring and summer of 1874 in Vienna, Bonn, and Rüschlikon on Lake Zurich. Hoping to further capitalize on his initial success and considering it a light relief from his work on his First Symphony, Brahms writes to Joseph Joachim. “If in January your wife wishes to sing new love-song waltzes, this nonsense will, unfortunately, be at her disposal.” In the event, Simrock was able to offer this “New” set for sale from September 1875.

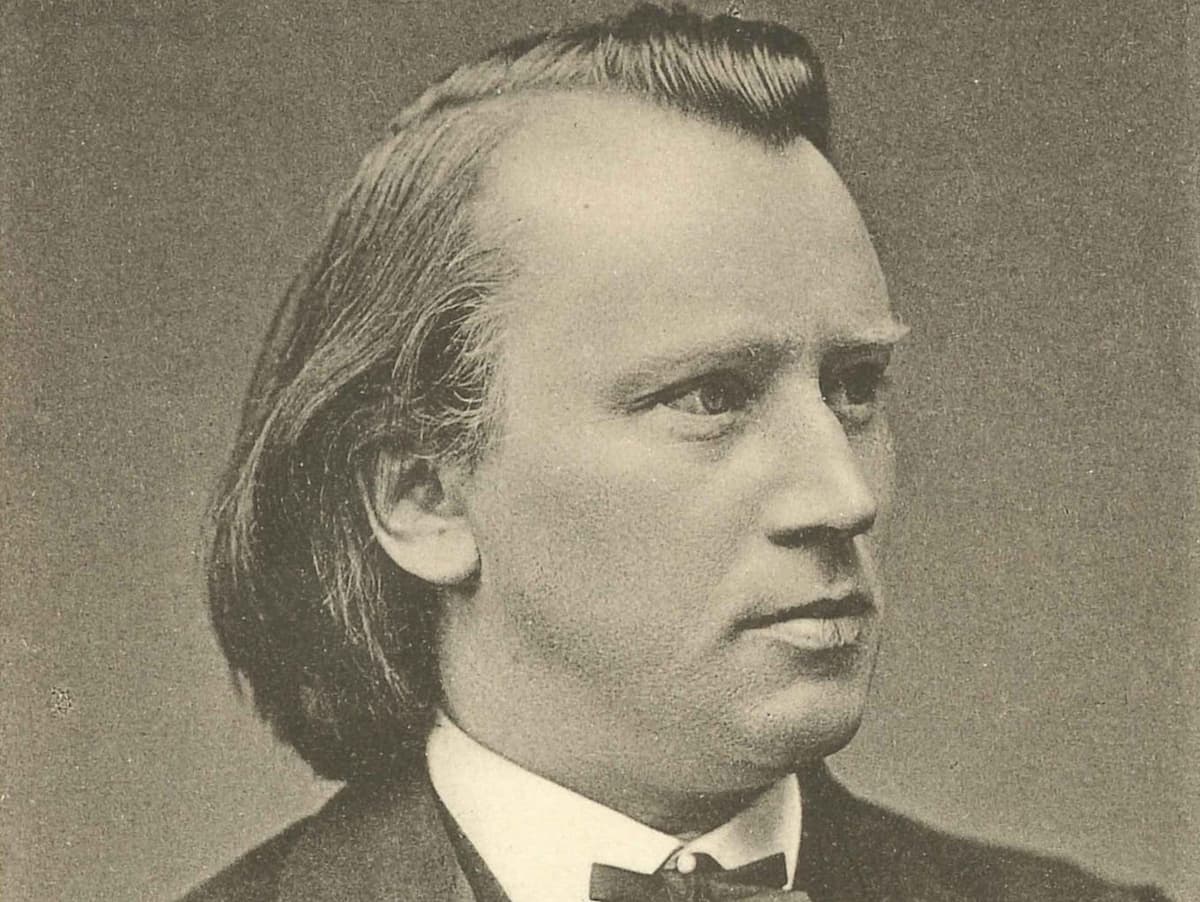

Johannes Brahms, 1874

Renounce, o heart, all hope of rescue,

when you venture on the sea of love!

For a thousand barges drift

and founder on the shore around!

(All English translations © by Richard Stokes)

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 1 “Renounce, o heart” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

In due course, Brahms was able to declare to his publisher that this “was the first time I have smiled at the sight of a printed edition of my work.” For his Neue Liebeslieder Brahms once again consulted Daumer’s Polydora, except for the final poem, which consists of the last four lines of the elegy Alexis und Dora by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Brahms once described Goethe’s poems “So perfect in themselves that no music can improve them.” In his Neue Liebeslieder Goethe gets the last word, “taking a step back from the obsessive many-faceted qualities of love explored by Daumer. Brahms writes to Simrock, “The last piece naturally has no number, but comes over attractively ‘in conclusion’ (Goethe).”

Rüschlikon on Lake Zurich

Dark, nocturnal shadows,

waves and whirlpool peril!

Can they who calmly linger

safely on the shore

ever understand you?

He alone can do so

who drifts in the stormy desolation

of high seas,

miles away from the shore.

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 2 “Dark, nocturnal shadows” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

In his poetic selection of his Opus 65 Brahms elected to cast his net somewhat wider. We find a Turkish text in No 1, a translation of Hafiz in No 2, a Latvian/Lithuanian text in No 3, a Spanish poem in No 6, a Serbian text in No 12, and a Malaysian-inspired poem in No 10. As such, they join and expand on the Russian and Polish influences that had dominated his Opus 52.

On the fingers of either hand

I wore the rings

my brother had given me

in affection.

And one after the other

I gave them to the handsome

but worthless young man.

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 3 “On the Fingers of either Hand” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

Daumer’s Polydora

The lyrics of the Neue Liebeslieder have a rigorously symmetrical structure, with the fourteen waltzes formed into two groups of seven, each group beginning and ending with a movement for the full quartet. However, this set has a much darker tone. Instead of little birds and forest moonlight, the lyrics tell of boats drifting all wrecked on the ocean of love; of cheating lovers; of dark eyes taunting, bewitching, and destroying. Brahms seems to dwell on the destructiveness of love and not on its pleasures.

With your dark eyes

a mere gaze is needed –

palaces will fall

and cities sink.

How in such a skirmish

should my heart,

that frail house of cards,

stay standing?

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 4 “With your dark eyes” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

Without doubt, the second set unfolds in a more melancholy manner. On the other hand, Brahms’s dexterity in adapting the waltz style to reflect the moods of the poems is more elegant than before. The roles of the performers are reversed compared to the first set in that the second was described as a work for ‘four voices and piano four hands’, and the voice parts are no longer indicated as optional. However, this collection too was published in an adaptation only for piano four hands as op. 65a, despite Brahms’s protestations.

Guard, good neighbour, guard

your son from harm,

for with my dark eyes

I intend to bewitch him.

Ah, how my eyes blaze

to inflame him!

If his soul is not kindled

your cottage will catch fire.

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 5 “Guard, good neighbour” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

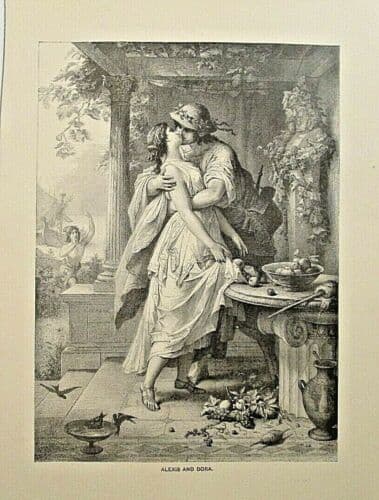

Wilhelm von Kaulbach: Alexis and Dora

The music itself is perhaps less playful and more complex, with “striking chromatic harmonies, jarring rhythms, and minor keys.” However, it is highly sophisticated, as Brahms prefers literal repetition, as a hallmark of popular music, in favor of continual variation. In addition, these waltzes feature finely spun counterpoint in the accompaniment, simultaneously containing a striking contrast between popular and art music. A scholar writes, “throughout this set, these opposing forces are played out with a sure hand.” I should also mention that there is a higher proportion of solo songs in this collection, “whether because Brahms simply felt they would be attractive to his customers, or because he felt these texts called for the lonely crying out of an individual voice in desolation or fury.”

My mother pins roses on me,

because I am so distressed.

She’s right to do so: the rose withers,

when stripped of leaves, like me.

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 6 “My mother pins roses on me” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

As in his original Op. 52 set, Brahms paid close attention to matters of order and arrangements. “Surviving manuscripts and other documents show that in some cases the question of the sequence of dances and their keys remained unsettled until it was time to go to press. Still, most adjoining dances are in closely related keys, and some waltzes share significant harmonic and motivic material. Brahms’s arrangements thus yield continuity between adjacent dances, coherence within larger units, and closure for each complete cycle.”

From the mountain, wave on wave,

the torrential rain teems down,

and I would dearly love to give you

one hundred thousand kisses.

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 7 “From the Mountain” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

Johannes Brahms’ New Liebeslieder Waltzes

Brahms was a voracious reader, and modern poetry was of particular interest to him. Initially, as he reported to a friend, “he read a poem as an uncritical aficionado, trying to adopt the poet’s point of view. Once a poem had attracted his attention as a candidate for musical setting, had “forced itself” on him, as he wrote to Mathilde Wesendonck, he evaluated it more critically, considering among other factors, whether it was already perfect in itself and thus provided no latitude for the composer. Through much of his lieder oeuvre, Brahms seemingly avoided setting works by great poets, with the occasional exception of Goethe. As far as literary authorities are concerned, Brahms followed the early Romantic practitioners and theorists by “setting many inferior poems of a banal nature.”

Soft grasses in the glade,

a quiet and pretty spot!

How blissful it is

to recline here with a lover!

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 8 “Soft grasses in the glade” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

According to critics, “well over half of his songs use mediocre to bad poem, and among the poets who incur such criticism are several whose texts Brahms set repeatedly: Carl Candidus, Klaus Groth, Friedrich Halm, Karl Lemcke, and above all Georg Friedrich Daumer.” We do know that the eroticism of some of the Daumer texts occasionally offended Brahms’ friends. And while critics repeatedly have pointed out the weakness of Daumer’s poetry, it nevertheless “evoked some of Brahms’s most compelling songs.” A scholar writes, “the listener cannot but be impressed by Brahms’ ability to identify with the emotional truth behind often undistinguished poems and place them in a setting that imparts the memorable resonance lacking in the words themselves.”

I feel a poison gnaw at my heart.

Can a young girl,

without yielding

to tender affection,

bear the thought

of a whole lifetime

devoid of bliss?

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 9 “I feel a poison” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

Johannes Brahms’ New Liebeslieder Waltzes

A good many commentators have accused Brahms of a lack of respect for his poetic texts, “especially with regard to declamation and the repetition of words, phrases, and lines.” For critics, Brahms as a composer let the music “outweigh the text.” However, as a Brahms scholar wrote, “Brahms, following Schubert, was influenced by the declamation, rhythmic patterns, and form of folk music, and the fact that the folk-like style of declamation was a valid compositional technique in the 19th century was quickly forgotten.”

I sweetly caress this girl and that,

grow taciturn and ill,

because always, always my thoughts

return, o Nonna, to you!

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 10 “I sweetly caress this girl” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

In his Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes Brahms deals more directly with the difficulties of amorous human relationships. Tense counterpoint, harsh modulations, chromatic harmonies, and exacting rhythms alongside minor keys underscore the more serious nature of the set. “The music is much darker and more passionate, and it is more difficult to perform…it creates such tension, and thereby potential problems for itself.

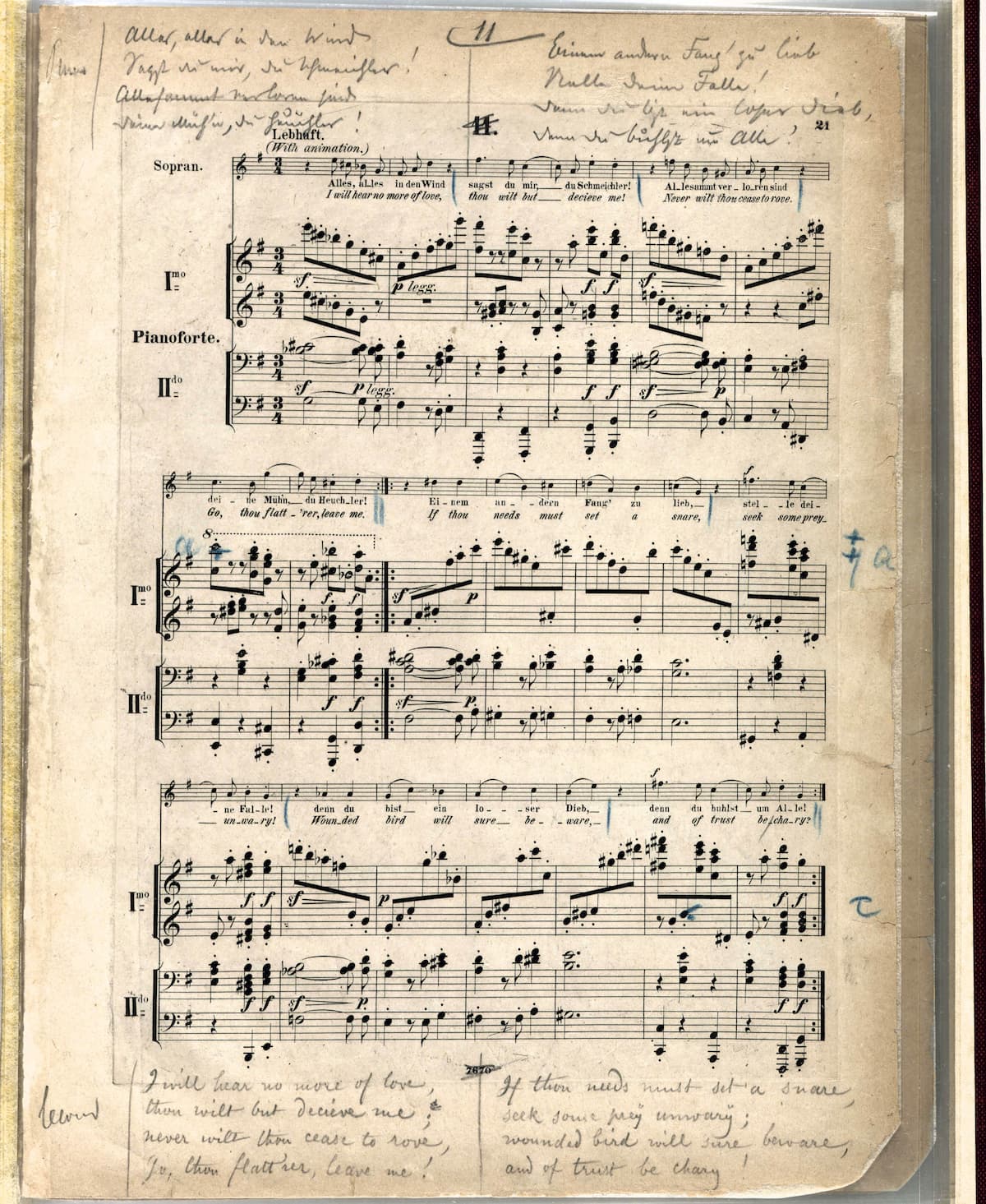

Everything you tell me, flatterer,

is wasted breath!

All your efforts are wasted,

you hypocrite!

Set your snares

for another victim!

For you are a wanton thief,

wooing all and sundry!

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 11 “Everything you tell me” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

Brahms had to find a way to diffuse the overall tension of the set and was probably searching for something in the Daumer collection to tie things up and bring them to a satisfying conclusion. In the end, he turned to Germany’s greatest poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe for a peaceful and soothing end, “appealing to the muses, who alone, according to both composer and poet, can calm the stormy seas of the human condition.”

Dark forest, your shadows are so sombre!

Your suffering, poor heard, so oppressive!

The one thing you value stands before you,

But a happy union is forbidden forever!

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 12 “Dark forest” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

Johannes Brahms by Rudolf Krziwanek

In the final movement, Brahms not only abandons Daumer, but he also dispenses of the waltz rhythm, replacing it with a serenade-like 9/4 time. It essentially serves as a coda, a kind of closing prayer to the entire composition. “The choral writing is reminiscent of Brahms’ sacred music, especially his a-capella motets, the sublime poet in this final lyric casts his gaze over the lover’s wounded heart, where sorrow and joy exchange places in an endless, restless struggle, and invokes, to still the storm, the ageless power of the classical Muses—the solace of mature, civilized wisdom, and the apotheosis of art.”

No, my love, do not sit

so close to me!

Do not gaze so fervently

into my eyes.

However much your heart might burn,

subdue your desire,

that the world might not see

how we love each other!

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 13 “No, my love, do not sit” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

The vocal quartet is entirely homophonic in structure, but supported by elaborate counterpoint in the piano. “Listeners and performers alike, are relieved to finally end all that dancing and arguing, and finally agreeing to disagree.” It seems an aptly symbolic conclusion to both sets of Liebeslieder Waltzes as it encompasses all the emotional paradoxes the work has moved through, with a sense of serene resignation. One cannot help but sense that part of Brahms’ personality and passions are present in this music. However, since he steadfastly refused to provide written explanations for the masses, he expressed and communicated the complexities of his personality in a unique compositional language that encoded his highly personal convictions and ideas.

Bold, adorable young man,

with fiery eyes and dark hair.

You are the cause that sorrow

has entered my poor heart.

Can the burning sun turn to ice,

can day turn into night?

Can an ardent human heart

breathe without passion’s glow?

Is the meadow drenched in light,

for the flower to grow in the dark?

Is the world so full of pleasure

for the heart to perish in grief?

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 14 “Bold, adorable young man” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)

The Liebeslieder Walzer are pure and quintessential Brahms. Though their charm may derive in part from the contrast in which they stand to his work as a whole, their eternal freshness stems from techniques refined in larger forms. As a critic put it, “had Brahms never been stretched to the tension of such works as the C-minor Symphony and the Requiem, he could never have relaxed to the charm of the waltzes.” This image tells a familiar story–of an uncompromising composer who brought the highest artistic sensibilities to every expression of his muse.

Enough, now, ye Muses!

You strive in vain to show

How joy and sorrow alternate

in loving hearts.

You cannot heal the wounds,

inflicted by Love;

but assuagement comes from you alone.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: Neue Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 65 No. 15 “Enough now, Muses” (Edith Mathis, soprano; Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano)