One of the most prevalent musical genres for over 500 years, the motet has virtually vanished from the performing repertoire. Throughout history, the motet changed with every new musical period. Beginning around 1220, the motet was a secular polyphonic composition with the tenor as the focus of the planning. The tenor, the lowest voice, sang repetitive rhythms while the upper two or three voices sang music at a faster rate, usually with a different text than in the tenor.

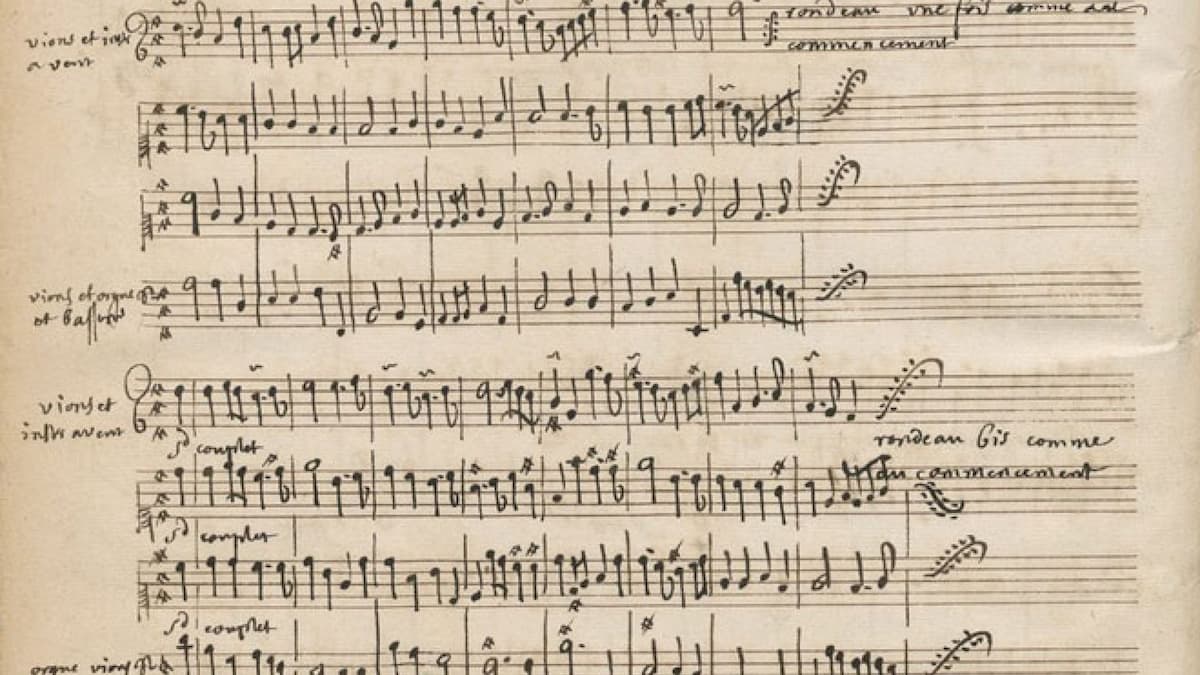

© cmbv.fr

In this motet by Guillaume de Machaut, the tenor comes from a melisma from matins of Holy Saturday (Amara valde). The other two voices sing two different texts, both on love, Quant en moy vint premierement Amours and Amour et biauté parfait, however, while the tenor is a repetition of the music for the two words ‘amara valde’, the top voice sings an extended text about love: ‘When Love first appeared in me/she wanted so sweetly/to make my heart fall in love’ while the middle voice, moving at a slower pace has only: ‘Love and perfect beauty’ and the tenor only sings 4 whole notes.

Guillaume de Machaut: Quant en moy / Amour et biaute / Amara valde (Kathleen Dineen, soprano; Lena Susanne Norin, alto; Eric Mentzel, tenor)

By 1450, the motet was no longer associated with secular music (as in the Machaut piece), but became part of the sacred song repertoire, setting a sacred Latin text.

In Josquin’s 5-voice motet Illibata Dei virgo nutrix / La mi la, the tenor line (la-ma-la) hides a reference to the Virgin Mary (Ma-ri-a) through its vowels.

Josquin des Prez: Illibata Dei virgo nutrix – La mi la (Weser-Renaissance Bremen; Manfred Cordes, cond.)

The motet in the Renaissance changed greatly, due largely to the ability of composers to travel: motets from France had a more relaxed structure than those from Italy and as the genres mixed, we see the top two voices becoming more equal, as we hear in the difference between Machaut’s and Josquin’s motets. Composers were also free to write their own base melodies, rather than having to derive them from sacred models (again Machaut (sacred model) and Josquin (newly composed tenor)). A freer flow of the text meant a better melodic flow and composers now felt free to change from triple time to duple time. The ability to have changes in texture and changes in mensuration contributed to the growth of the motet as the showoff piece for a composer.

It was in the Baroque that the motet fell from its preferred position but not for lack of devotees, but because there were so many more sacred vocal genres to write in, such as the cantata. By the 17th and 18th centuries, a motet was ‘any kind of vocal music with liturgical affiliations.’ Catholic motets were in Latin and Protestant motets were mostly in the vernacular. Motet also came to mean an ecclesiastical style coming from 16th-century models, such as Palestrina.

© BBC Music Magazine

A motet such as Palestina’s ‘O magnum mysterium’ is clear in form and often divides the voices into smaller sub-combinations to produce the illusion of alternating choirs.

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: O magnum mysterium (Palestrina Choir; Michael Harrison, cond.)

By the time we get to Bach, however, the motet is far from Palestrina’s style. Soloists come to the fore, with the choir as a whole reserved for the chorale sections.

Bach only wrote 7 motets, but they are considered the high point of the genre in the 18th century. In ‘Ich lasse dich nicht’, BWV Anh. 159, Bach is in the middle-German cantabile style.

J.S. Bach: Ich lasse dich nicht, du segnest mich denn, BWV Anh. 159 (Bach Choir of Bethlehem; Bach Festival Orchestra; Greg Funfgeld, cond.)

Contrast this with the motet ‘Singet dem Herrn‘, BWV 225, where Bach sets a Biblical text (Sing unto the Lord a new song). This motet follows a more Italian instrumental concerto form by being divided into the typical fast-slow-fast form but closes with a distinctly non-Italian four-part fugue.

J.S. Bach: Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, BWV 225 (The Scholars Baroque Ensemble)

It is thought that this motet dates from 1726 or 1727 and might have been created for the birthday of Friedrich August, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony.

After 1750, the motet essentially vanishes from music history. Secular music and sacred music started to diverge so strongly at this point that the motet became isolated in a limited backwater. Mozart’s motets are not about faith so much as being flashy pieces. Other of Mozart’s motets were academic pieces, such as ‘Quaerite primum regnum Dei’ K. 86, which was a piece he had to write for admission to the Accademia Filarmonica.

In the 20th century, the 1903 Motu proprio of Pope Pius X virtually banished any theatrical styling of the motet. The last great motets were probably English composer Bernard Naylor’s 9 Motets of 1952.

Naylor: 9 Motets: No. 2. Christmas Day (Salisbury Cathedral Girl Choristers; Salisbury Cathedral Lay Vicars; David Halls, cond.)

And so, a genre, once the most important in sacred music, vanishes.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter