Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) first fell under the influence of Balinese music when he met the Canadian composer Colin McPhee (1900–1964) in New York in 1939. McPhee had just returned from 6 years in Bali and in 1940, wrote his highly influential Music in Bali reference book. McPhee included Balinese musical ideas in his own compositions but it wasn’t until Britten’s own visit to Bali in January 1956 that he recognized the ‘remarkable culture’ of Bali.

Benjamin Britten: The Prince of the Pagodas, Op. 57 – Act I: Prelude (Royal Opera House Orchestra, Covent Garden; Benjamin Britten, cond.)

At the time, Britten was struggling through a commission from Sadler’s Wells ballet company for a full-length ballet. After visiting Bali, however, his ideas crystalized and Prince of the Pagodas was born. It was his exposure to non-Western sounds and musical structures that provided inspiration for Britten, even to the point of including an extended sequence in Act II.

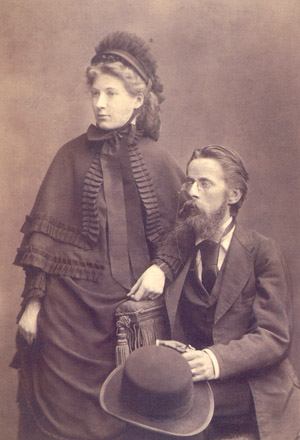

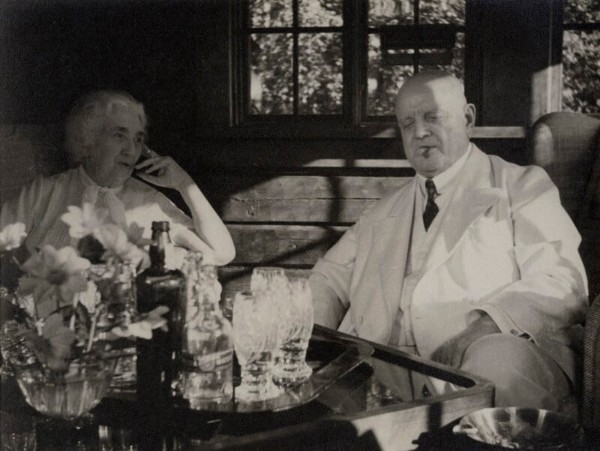

Britten and Peter Pears in Bali, 1956

Benjamin Britten: The Prince of the Pagodas, Op. 57 – Act II Scene 2, “The Arrival and Adventures of Belle Rose in the Kingdom of the Pagodas”: The Pagodas (Royal Opera House Orchestra, Covent Garden; Benjamin Britten, cond.)

The Story

The story is of a royal succession: the Emperor must chose between his two daughters to be his successor: the wicked Belle Epine or her younger sister Belle Rose. He invites kings from the four corners of the world to court his elder daughter, but they prefer the younger daughter. In anger, Belle Epine usurps the throne and imprisons her father in a cage. Belle Rose escapes to Pagoda Land (pagodas in this ballet are small porcelain figures with movable heads) with the help of magical flying frogs. There, she meets a Prince who is disguised as a green salamander. When Belle Rose returns to the Imperial court, the green salamander follows her and rescues her from capture just as Belle Epine’s guards are about to seize her. ‘The Court disappears in a clap of thunder and the lights come up on the Pagoda Palace. Happiness prevails, and, following a large-scale divertissement, the ballet ends triumphantly’.

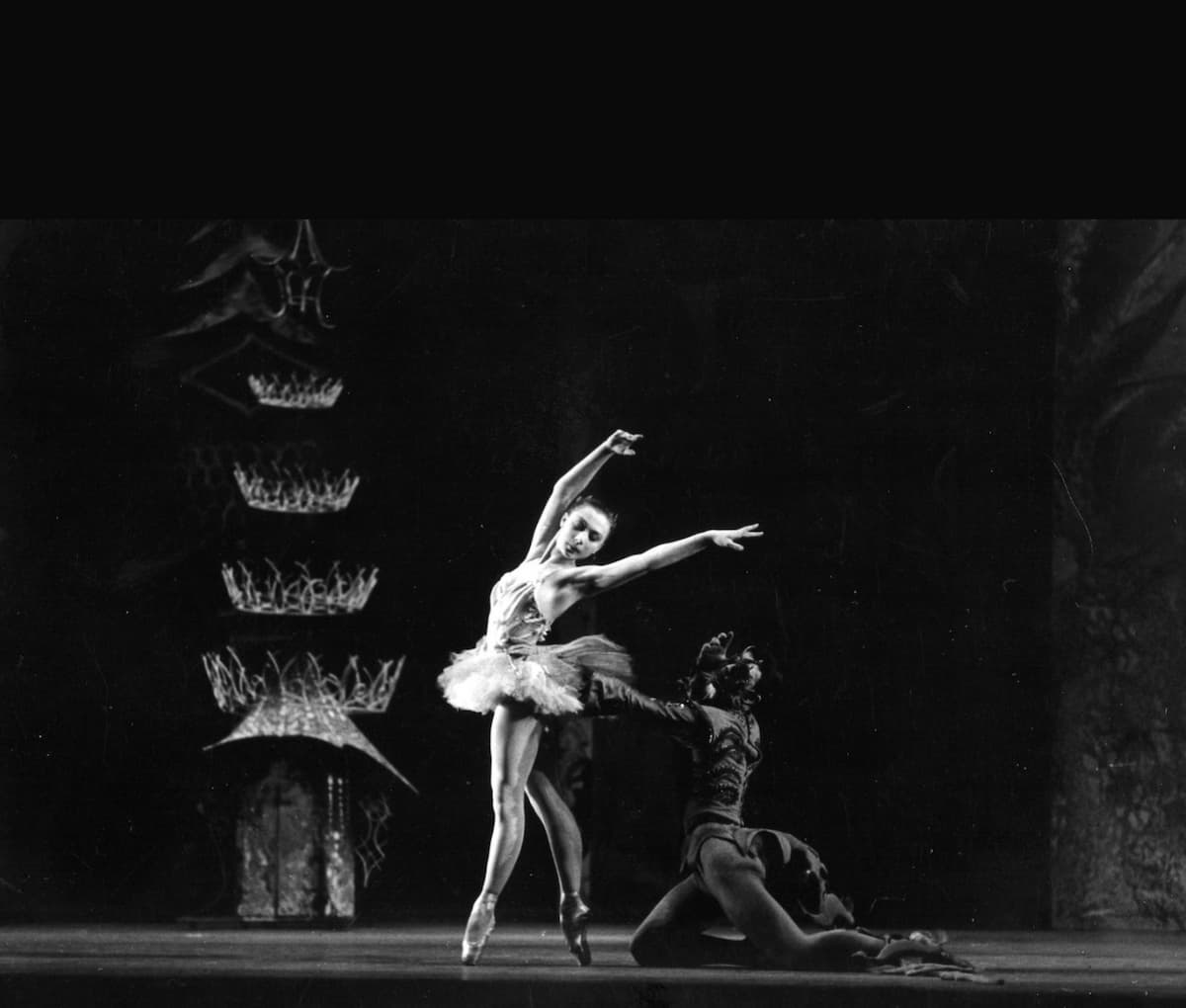

Svetlana Beriosova as The Princess Belle Rose and David Blair as The Green Salamander in the Sadler’s Wells Ballet production of The Prince of the Pagodas, 1957 (Royal Opera House Covent Garden) (Photo by Roger Wood)

The story was developed by choreographer John Cranko and the draft scenario was called The Green Serpent. He brought together elements from King Lear, Beauty and the Beast, and the French fairy tale Le Serpentin Vert (The Green Serpent) by Marie Catherine D’Aulnoy from 1698, itself a version of the Eros and Psyche myth. Cranko gave Britten a list of required dances and timings and left him to his own devices.

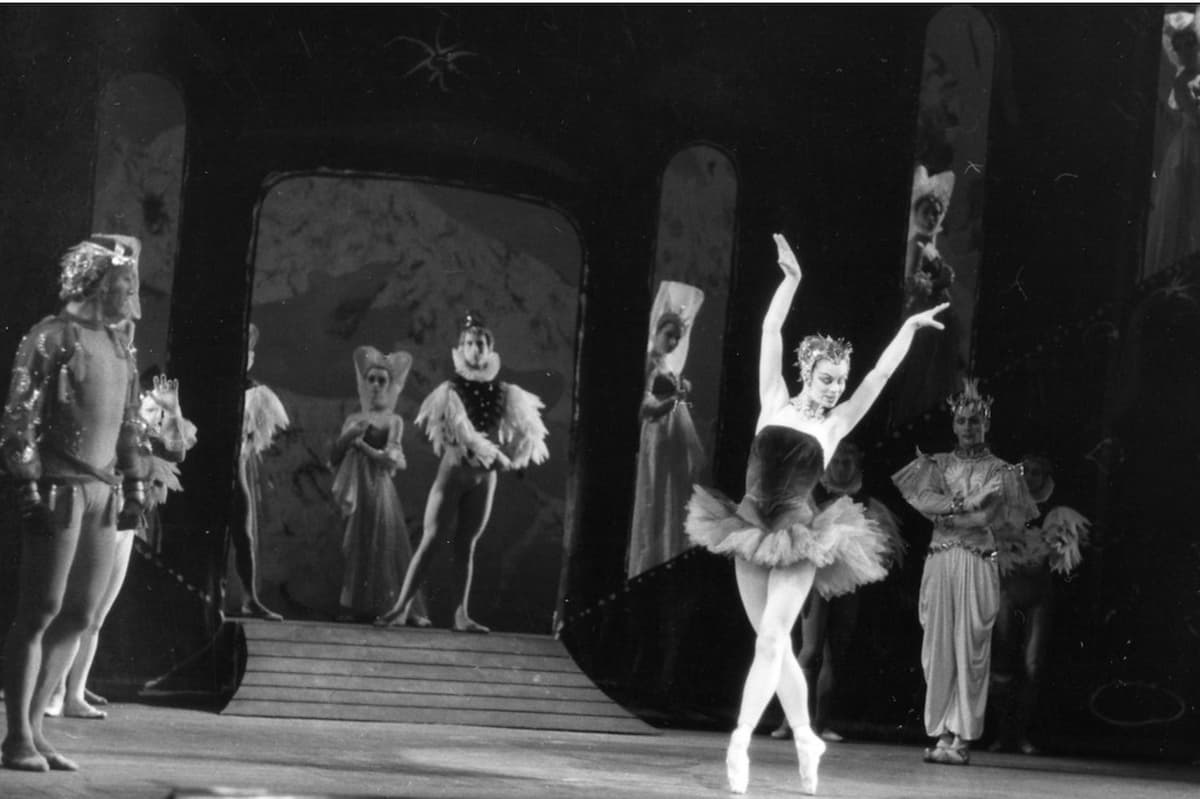

Julia Farron as The Princess Belle Epine in the Sadler’s Wells Ballet production of The Prince of the Pagodas, 1957 (Royal Opera House Covent Garden) (Photo by Roger Wood)

The Premiere

Britten struggled with the score, his only full-length ballet and one of his rare instrumental-only compositions. Eventually he succeeded and the ballet had its debut at Sadler’s Wells in 1957. The problem was that Britten provided too much music and refused to permit changes to the order of the score or to let it be cut. After Sadler’s Wells, Cranko tried the ballet in Stuttgart and in Milan at La Scala before retiring the work and dropping it from the repertoire.

Other choreographers tried to bring it back to the stage. The first was Kenneth Macmillan with the Royal Ballet, with the help of novelist travel writer Colin Thubron to revise the story line.

Macmillan wrote it for his 19-year-old prima ballerina, Darcy Bissell, who created a character that could travel from innocence to experience and still be the same forthright and compassionate self.

Darcy Bussell as Princess Rose, 1989 (Royal Ballet) (Photo by Leslie E. Spratt)

Now, instead of it being only a fairy tale, it has become a rite of passage for the heroine, Princess Rose. Still the Britten Estate would not allow the music to be cut. The new story, a combination now of fairy tale and Freudian psychology, could not be supported by the score. After the first year, the Britten Estate agreed to cuts, but the ballet was still unbalanced.

The Princess (Darcy Bussell) and the Prince (Jonathan Cope), pas de deux, 1989 (Royal Ballet)

English choreographer David Bintley took the story up in 2014 for the National Ballet of Japan. Bintley moved the story to Japan: ‘The evil Épine is now stepmother to Princess Belle Sakura, a cold, avid schemer attempting to wrest political control from Japan’s enfeebled Emperor.

David Bintley: The Prince of the Pagodas, 2014 (Birmingham Royal Ballet) (Photo by Peter Doherty)

The Salamander Prince becomes Belle’s older brother, exiled and cursed by Épine while still a child. The result is that the Princess Belle is more active as a heroine and there’s no love story. Bintley noted that Britten’s music really doesn’t contain a love story and that some of the traditional love dances, such as the pas de deux, are more like fights in Britten’s music. That’s when he came up with the idea of reinventing the ballet as a ‘story of two siblings battling to restore moral order to their world’.

Benjamin Britten: The Prince of the Pagodas, Op. 57 – Act III Scene 2, “Belle Rose’s Triumphant Return and Marriage to the Prince of the Pagodas”: Finale (Royal Opera House Orchestra, Covent Garden; Benjamin Britten, cond.)

A review of Bintley’s 2014 production in Birmingham with the Birmingham Royal Ballet praised his work but said that the music was ‘still waiting for the right choreographer to bring it fully alive’.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter