Every now and then, the people who enjoy, love, or seek out music undergo a very special kind of occurrence. It could happen at an exciting concert or festival or merely in the fabric of day-to-day life: listening to algorithm-recommended music on one’s commute, tuning in to the radio while cooking dinner, or watching a movie.

The moment of which I speak is when you encounter a piece of music, perhaps for the first time, and you feel moved.

Musical analysts would call this moment one thing, music psychologists another, music historians or semiologists yet another, and it’s unclear if anyone yet understands exactly why or how this happens – and yet, this response is fundamental to so much of our human music-making. I myself like to think of this moment as a kind of affinity – some part of you responds to the music you’re hearing, resonating in sympathy with what you hear, affecting you.

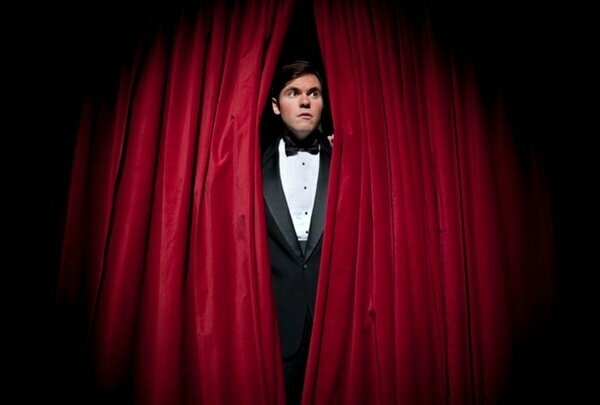

Portrait of Scarlatti wearing the Order of Santiago (1738)

Often, you won’t forget that piece; you’ll want to hear it again, add it to a playlist, make a mental note to buy the CD or vinyl or go see it in concert. That piece has become part of your musical identity and story, and you may revisit it throughout the course of an entire lifetime. Some such pieces may be so well-listened that they become a kind of home away from home, the first familiar notes like the greeting of an old friend.

One such piece for me is Domenico Scarlatti’s piano sonata in A major, K. 208. It’s by no means one of Scarlatti’s best-known sonatas, though its inclusion in a recent ARSM diploma syllabus has helped to make it better known amongst a new generation of pianists. I myself first encountered it in a small parish recital given by a friend in West London, and I was – in no exaggerated terms – entranced from the very first phrase.

Part of my love for this sonata comes from Scarlatti’s subtle and masterful handling of the bass register. At the opening, he grounds us unambiguously in A major with an insistent crotchet chime of a fairly high (for the left hand) A – there is no doubt as to where we are harmonically, and yet the sound is ethereal, floating, the melody clear as crystal water without being muddied by other chord tones. The first little grace note, letting the melody reach a little higher than it has to and then settle onto the expected E, hints at all that makes this sonata’s melody undulating and lovely: its especially sinuous and fluid quality. It is one of the most beautifully crafted melodies I have ever encountered, and its vocal quality is such that I can rarely resist singing along when I play it, à la Glenn Gould.

Sometimes proceeding in even, stately crotchets, the melody soon bends and flexes around the steady tempo of the left hand like water, cascading briefly in a delicate run here, falling lazily behind in a quaver syncopation there. Often, Scarlatti emphasises a brief, delicious moment of harmonic tension on the strong beats before swiftly resolving, creating moments that are piquant and always remind me of the musical language of jazz. Throughout the first half, we progress by logical step and transposed motive through Scarlatti’s tonal plan, enacting moments of harmonic drama in different ways: sometimes becoming more ornamented, quick, and scalic, and at others moving simply and powerfully by way of larger, stronger intervals and more obvious patterning. Throughout, the voice-leading in the bass is thoughtful, and the voicings are lovely, with gentle chromatic inflections and crispy seconds for added harmonic crunch. Ralph Kirkpatrick describes Scarlatti’s use of the bass in a wonderfully astute and playful way:

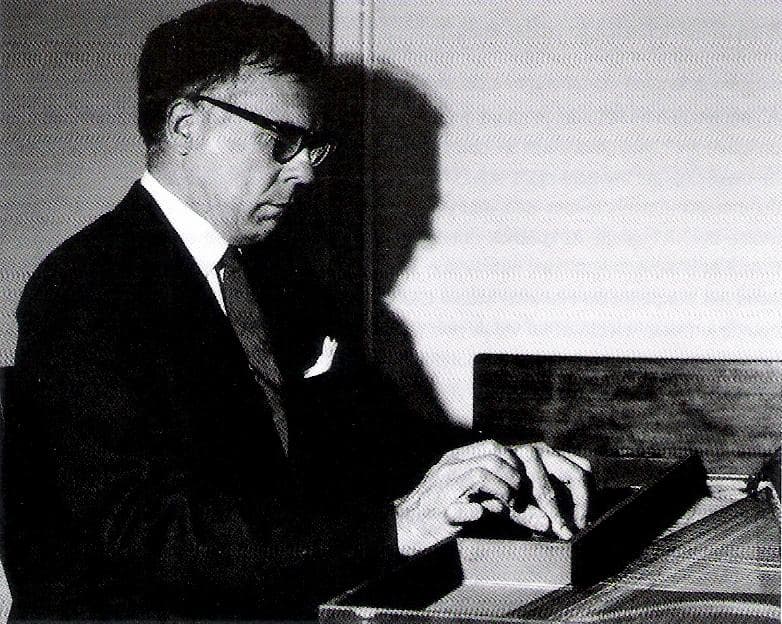

Ralph Kirkpatrick

In the moments of uncertain tonality, modulatory passages or transitions, the basses often move in cautious stepwise progressions like a fencer jockeying for position, cling to pedal points like a quivering cat about to spring or undulate from side to side of a dominant like a dancer maintaining movement in a limited space.

After bringing the A section to a close with a delicate and rather effortless-feeling little trill, the B section pulls us through a genuine, forlorn distance from our home key. This harmonic movement of this journey is propelled by melismatic scalic figures that are tied over the bar so as to let us hear the changes in the bass, creating in my mind something of a ‘tripping forwards’ – a feeling of tumbling, accumulating and an inevitable drive.

This particular sonata, written during Scarlatti’s employ by the royal Spanish court, was part of a stylistic shift in Scarlatti’s keyboard writing towards new veins of lyricism, more slow movements, and “even a certain quality of introversion”, according to Kirkpatrick. In a greater mellowness and tempering of previous virtuosic harmonic excursions, these middle-period royal sonatas play out as “warm, free, and direct communications of experience,” says Kirkpatrick. He imagines this particular sonata:

Perhaps K.208 is Scarlatti’s impression of the vocal arabesques spun over random guitar chords in long arcades of extended breath, such as are still to be heard among the gypsies of southern Spain. This is courtly flamenco music, rendered elegant and suitable for the confines of the royal palace.

Coming back to our very opening point about moments of musical chemistry, I think it’s important that when lightning strikes – when a piece moves us – we wonder why. This shouldn’t feel like a chore but rather serve to increase our enjoyment of the piece by way of a more intimate knowledge of both the music and ourselves. This doesn’t have to take the form of harmonic analysis, necessarily – we can ask ourselves how our body feels when playing it (this Scarlatti fits so effortlessly under the fingers), what emotions we feel, what kind of narrative we imagine the piece evokes, or what genre conventions or well-known gestures the composer is toying with. Learning about the composer’s life and the context in which they worked is another way of doing this. In any case, I think what I like most deeply about this sonata is its quiet, understated, introverted quality. The melody remains always a single line without bifurcation, floating rather high above its harmonic accompaniment, unfolding at its own pace and with its own clear logic.

Scarlatti was often inspired by dance, and his music is often analysed in this context. Some of his works bring to life the most lively and social of dances, such as the jota of K.209, and what Kirkpatrick calls “a dizzying whirl of twinkling feet, stamping heels, and shrill village instruments.” If K.208 were a dance, it would perhaps be the free and meandering spins and steps of a lone figure, humming to themselves as they stumble home under the moonlight. A little tipsy from wine, bittersweet from the joy – and sorrow – of being alive.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter