Ruth Crawford-Seeger

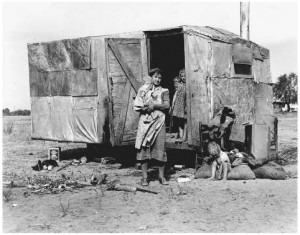

In music, Ruth Crawford-Seeger (1901-1953) also advocated a change of direction. Surrounded by desperate poverty, Crawford-Seeger felt strongly that making art only for aesthetic reasons was absurd. “It became almost immoral to closet oneself in one’s comfortable room and compose music for its own delight.” As such, she composed avant-garde classical compositions with a clear political message. By transcribing and incorporating folksongs into her work, she was looking to move political ideas across American social classes. Crawford originally hailed from rural Ohio, but her family eventually moved to Jacksonville, Florida. A talented writer and poetess, Ruth also had considerable musical talents and eventually decided to pursue a career as a concert pianist. However, during her years at the American conservatory of Music in Chicago, her focus gradually shifted from performance to composition. In 1930 she became the first woman to receive the Guggenheim Fellowship and traveled to Berlin and Paris to further her studies. She married the musicologist, composer and teacher Charles Seeger in 1932, and her work at the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress resulted in various arrangements, transcriptions and interpretations.

Crawford-Seeger’s transcriptions of folksongs and her original compositions attempted to communicate a political message to an educated class. Her work “served to unite people of different class backgrounds, and her folk music collection for children were widely used in schools to foster feelings of national belonging and heritage.” Crawford-Seeger wrote, “People can be made aware that many of the songs about their everyday lives … are songs of merit. This gives them a new sense of dignity and pride in their cultural heritage….The folk song grows out of reality. It is this stark reality and genuineness, which gives the folk song vitality and strength.” However, Crawford-Seeger was also a powerful modernist composer, and her attempt to use high art in the service of social progress were not entirely successful. Nevertheless, her idea of placing music education in the service for a new national democratic order substantially enriched the American tradition of classical music.

Crawford-Seeger’s transcriptions of folksongs and her original compositions attempted to communicate a political message to an educated class. Her work “served to unite people of different class backgrounds, and her folk music collection for children were widely used in schools to foster feelings of national belonging and heritage.” Crawford-Seeger wrote, “People can be made aware that many of the songs about their everyday lives … are songs of merit. This gives them a new sense of dignity and pride in their cultural heritage….The folk song grows out of reality. It is this stark reality and genuineness, which gives the folk song vitality and strength.” However, Crawford-Seeger was also a powerful modernist composer, and her attempt to use high art in the service of social progress were not entirely successful. Nevertheless, her idea of placing music education in the service for a new national democratic order substantially enriched the American tradition of classical music. Ruth Crawford-Seeger: String Quartet, III, IV