During this extraordinary period of one’s musical career – at the height of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic – every teaching musician affected by lockdown has a single professional goal: instrumental lessons must be kept safe, personal and inspirational, and pupils’ continuity of learning needs to be safeguarded so as to keep musical progress at pace.

During this extraordinary period of one’s musical career – at the height of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic – every teaching musician affected by lockdown has a single professional goal: instrumental lessons must be kept safe, personal and inspirational, and pupils’ continuity of learning needs to be safeguarded so as to keep musical progress at pace.

To assist with the transition to the necessity of online-only lesson delivery, there are many helpful articles giving specialist advice and information on technology, teaching styles and safeguarding. With this in mind, I decided nonetheless to ask not fellow colleagues but rather a longstanding pupil in order to identify what has changed for them since lessons – for better or for worse – and to reflect on the results in order to enhance our online lessons further.

Sarah, who has learned with me for over two years, recommenced her musical learning in her sixties with a significant aim – to achieve personal fulfilment by developing not only her practical and expressive but also her theoretical skills. Despite much progress to date – she recently achieved her Grade 8 Theory – there is also a sociable dimension: although not the priority, I think it would not be a push to say that for a lady who lives alone (contentedly so), the regularity of structured one-to-one lessons are particularly welcome – making the present climate particularly challenging.

I asked Sarah to consider what is better or worse about online music lessons compared with the traditional model, and her answers were surprising. The first loss has been “the ability to play together”, and though I was initially sad to read that the answer points towards a recognition of the music’s most important social dimensions, expressing a desire to converse and to exchange ideas in a non-linguistic context.

Matthew Schellhorn

If there are occasions when Sarah wonders whether “technology struggles to feed comfortably and seamlessly into live music-making”, on the other hand one can “look back” on lessons in a sometimes more reliable way. Online platforms allow for recordings to be made, which can be used to extend the learning process and to focus on clear learning objectives at a pace that suits oneself. She looks at these recordings “regularly and frequently, often several times over” – though with the lessons stored (with her consent) in my Dropbox, she is blissfully unaware of the data cost!

And in any case, as I have often said to pupils during better times – and which recording musicians know first-hand – seeing and hearing oneself perform is a learning experience in itself. In Sarah’s words: “I can hear much more easily in the recording what I am doing badly, and then, how to correct mistakes.”

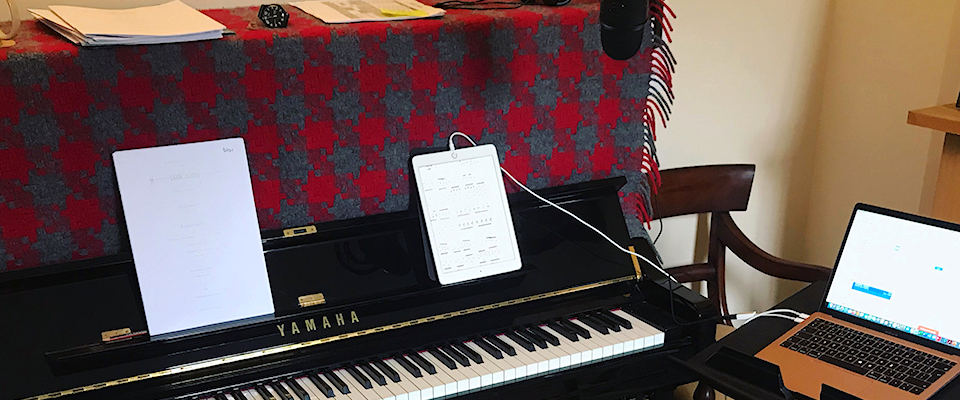

Despite the fast-moving pace of technology, Sarah has found the technology (we use zoom, with Adobe Acrobat supplying the means of marking scores and notational work) surprisingly “intuitive and easy to use”. In the area of annotation, then, lessons remain unchanged, and although I think the pace is perhaps somewhat slower my pupil feels that it is “generally unchanged”.

This last response suggests that online learning enjoys the same complexity as the usual model: teaching and learning can be experienced differently, and on the subject of “pacing” it is always important to check perceptions and to base reactions on a pupil-centric perspective.

This last response suggests that online learning enjoys the same complexity as the usual model: teaching and learning can be experienced differently, and on the subject of “pacing” it is always important to check perceptions and to base reactions on a pupil-centric perspective.

Finally, this pupil thankfully considers that online-only lessons have led to a marked increase in navigating accident-prone performance moments. Sarah’s view is that the medium has equipped her with the tools to “reflect on where mistakes occur and why”. And I must add that I have noticed a greater depth to her musicality, which is possibly to do with removing the self-consciousness whereby a proximate audience can become for some pupils a drawback.

As I reflect on these responses, I notice with a degree of surprise that the answers were not entirely as I expected. My goals must, despite the temptation to become ever more self-centred while confined at home, remain those of my pupils’. Teaching is, after all, not all about me – though neither is the learning all about the pupil. Music allows us, particularly in the worst moments of life, precious moments of togetherness.

A leading performer for over twenty years, Matthew Schellhorn regularly appears at major venues and festivals throughout the UK and has recorded numerous critically acclaimed albums. Described as a pianist of “searching intelligence and magnificent technique”, he has a distinctive profile displaying consistent artistic integrity and a commitment to bringing new music to a wider audience. In addition to his work on the concert platform, Matthew Schellhorn is a passionate educator and communicator, giving regular masterclasses and workshops in the UK and abroad.He has visited many university music departments and conservatoires to talk about his work in a wide range of performance contexts, including performance practice, commissioning and interpreting new works, working with today’s composers and bringing out fresh ideas in the interpretation of well known repertoire. He maintains a private teaching practice from his home in London. www.matthewschellhorn.com