Credit: http://hk-magazine.com/

Puccini: Turandot: Act I: Popolo di Pekino!

We open with the poor Prince of Persia, who has failed to guess the riddles, and whose head will now adorn the walls of the palace. As Turandot makes her appearance, our hero, Calaf, who has just found his long-lost father, the deposed King of Tartary, falls instantly in love and puts himself into competition for her hand, despite his father’s pleas and those of his father’s faithful servant, Liù.

Turandot poses her questions in a distinctive style:

Puccini: Turandot: Act II, scene 2: Straniero, ascolta!…Nella cupa notte

He answers them successfully and after she pleads to her father, the Emperor, to let her off completing her part of the puzzle, i.e., giving herself to the stranger, he reminds her that “Oaths are sacred.” Seeing her torment, our hero offers her an out: if she can discover his name before dawn of the next day, she can have his head.

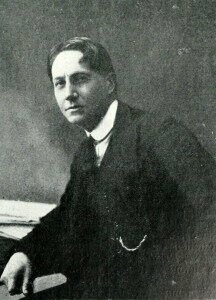

Franco Alfano

Credit: Wikipedia

What’s wonderful about this scene is that not only does he throw his riddle to her in the same melody that she used for her riddles, but as he explains the conditions, we hear, underneath, hints of his own special aria to come at the beginning of the next act: “Nessun dorma.”

Puccini: Turandot: Act III, scene 1: Nessun dorma

Turandot’s soldier’s search the town through the night, and finally find Calaf’s father and Liù. Liù offers herself up as the only person who knows the mysterious stranger’s name but will not give it up because of her love for him. After an impassioned aria, she seizes a knife and kills herself rather than reveal his name.

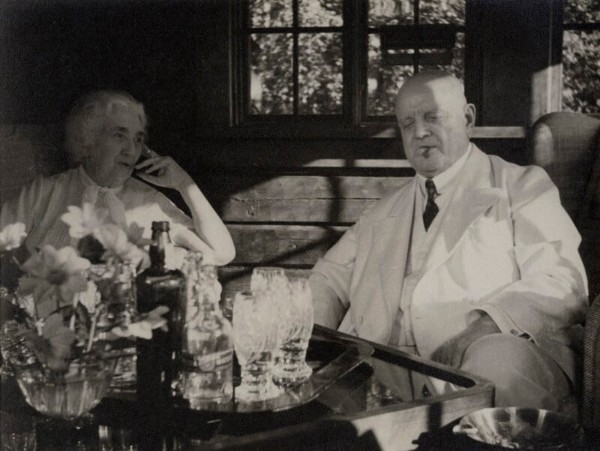

Luciano Berio

Credit: http://www.thing.net/

And with the death of Liù, we also had the death of the composer. Puccini died before finishing the final scene, where Turandot must be turned from the icy princess of death to the princess of love that Calaf knows she could be.

Puccini wanted composer Riccardo Zandonai to finish the work but Puccini’s son chose Franco Alfano to complete the opera from the extant sketches. His first version was rejected by Puccini’s publisher, Ricordi, and the conductor Arturo Toscanini as having too much Alfano in it. His second version was accepted and the first production was given in 1926. Unfortunately, much of Puccini’s compositional advances were beyond Alfano’s skills and Alfano hauls us back to the 19th century for his ending. In 2002, Puccini’s publishers, Ricordi, engaged the modern Italian composer Luciano Berio to write another ending, using the same materials that had been made available to Alfano. Berio is able to take Puccini’s modernism and incorporate it into finishing the opera. But, it’s not Puccini. It’s more advanced than Alfano, but it goes into a modern mode that was beyond even Puccini’s.

After the death of Liù, there is a meeting, in the early dawn, between Turandot and Calaf, where he kisses her. After her aria where she tells of her uncertainty, he tells her his name, placing his life in her hands. The audience is left truly unsure of what the volatile princess will do next: reveal his name and take his head, or conceal his name and take his hand.

In Alfano’s ending, starting at 2:01:25 in the video where she learns her suitor’s name from his own lips, we hear the riddle music as she debates what to do with this knowledge– Alfano’s setting gives the knowledge a life-or-death value, just as the riddles did in the first act. When she gives her father the stranger’s name, she accepts Calaf and takes his earlier words to heart that she isn’t losing herself, she’s coming into her own glory.

In the final scene by Berio, we start later where she’s announcing his name to the court. Turandot begins again with the riddle music and then announces his name: “Love.”

But is it? In Berio’s setting, it’s anticlimactic. Meh, it’s “love.” After her announcement (at 00: 34), despite the invisible chorus’ “ahs” in the background as the couple go off together, there’s no feeling of consummation or happiness, or even love. The audience is truly left uncertain if she loves him or if this is just her way of finding an equally bloodthirsty partner. In the recent production by Musica Viva in Hong Kong, this scene ended with the entire chorus on their knees on stage in supplication to the future horror at the even more evil reign of two of the most self-centered nobles in the Middle Kingdom. Even the final chord is tinged with menace.

If Alfano takes to the glorious Italian opera writing of the 19th century and uses a bit of Puccini in the process, Berio takes us to the cynical 21st century, where even love is tinged with irony.

I prefer Alfano’s ending, we need some happiness in this period of lockdown, uncertainty and a lot of doom and gloom. Bring back happy endings

The Met Opera’s Zeffirelli production, which I saw last Sunday (Oct. 24), makes Turandot appear to hint at herself at the end of the third riddle. The libretto’s first words by Calaf, “La mia vittoria ormai t’ha dato a me”, properly meaning “My victory aha-now has given you to me”, are rendered on their English titles as “My victory now you have let me win”—as if the Italian had “tu hai” not “t’ha”. Then Turandot recoils back behind her attendants. This connects to what she says in her aria “Del primo pianto” toward the end of Act 3. I won’t say it’s convincing, but above all this is a fable—and Gozzi in his original 1762 play has Turandot yank Calaf’s chain twice at the very end to convert his victory to hers while still wearing black to her wedding (see David Nicholson, “Gozzi’s Turandot: A Tragicomic

Fairy Tale”, Theatre Journal, Dec. 1979).