Frequently referred to as the ‘New Testament’ of piano music (Bach’s ‘Well-Tempered Clavier’ being the ‘Old Testament’), Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas rank amongst the high Himalayan peaks of the pianist’s repertoire. The primary appeal of these pieces, aside from the sheer Herculean effort of learning and absorbing them, is that they offer both a far-reaching overview of Beethoven’s musical style and a glimpse into the inner workings of his compositional life and personality.

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven

As pianists, whether amateur or professional, advanced or intermediate, or even just beginning on the great journey of exploration, we have all come across Beethoven’s piano music, and many of us have played at least one of his sonatas during our years of study. As an early student, a taster of a proper sonata may come in the form of one of his Sonatinas. Later on, we might encounter one of the “easier” piano sonatas, such as the pair of two-movement sonatas that form the Opus 49 (nos. 19 and 20)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 19 in G Minor, Op. 49, No. 1 (Louis Lortie, piano)

Early Period:

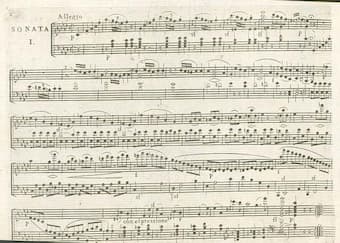

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 2 No. 1 First edition

Beethoven composed the piano sonatas during three distinct periods of his life, and as such they offer a fascinating overview of his compositional development. Setting aside the three “Electoral” sonatas, which are not usually included in the traditional cycle of 32, the early sonatas are, like the early duo sonatas for violin and for cello, virtuosic works, reminding us that Beethoven was a fine pianist. While the faster movements may hark back to his teacher, Haydn (though Beethoven would strenuously deny any influence!), it is the slow movements which demonstrate Beethoven’s deep understanding of the capabilities of the piano, and its ability, through textures and colours, moods and contrasts, to transform into any instrument he wishes it to be. In the early sonatas, Beethoven’s mastery of the form is already clear, and many look forward to the greater, more complex, and more revolutionary sonatas of his ‘middle’ period. His distinctive musical personality is already stamped very firmly on these early works.

Middle Period:

The sonatas from the middle period are some of the most famous and most popular:

The ‘Tempest’ and ‘La Chasse’ (Op. 31, Nos. 2 and 3). The first with its stormy, passionate opening movement, the second of the opus rollicking and somewhat tongue-in-cheek.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 17 in D Minor, Op. 31, No. 2, “Tempest” (Daniel Barenboim, piano)

The ‘Moonlight’ (Op. 27, No. 2): the first of his piano sonatas to open with a slow movement. Too often the subject of clichéd, lugubriously romantic renderings, this twilight first movement shimmers and shifts. An amazing gesture, created by a composer poised on the threshold of change.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27, No. 2, “Moonlight” – I. Adagio sostenuto (Vladimir Horowitz, piano)

The ‘Waldstein’ (Op. 53). Throbbing quavers signal the opening of one of the greatest of all of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, while the final movement begins with a sweetly consoling melody which quickly transforms into daring octave scales in the left hand and a continuous trill in the right hand. This is Beethoven at his most heroic.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 21 in C Major, Op. 53, “Waldstein” – I. Allegro con brio (Claudio Arrau, piano)

‘Les Adieux’ (Op. 81a). Suggested to be early ‘programme’ music in its telling of a story (Napoleon’s attack on the city of Vienna which forced Beethoven’s patron, Archduke Rudolph, to leave the city, though this remains the subject of some discussion still). It is true that Beethoven himself named the three movements “Lebewohl,” “Abwesenheit,” and “Wiedersehen”. One of the most challenging sonatas because of its mature emotions and technical difficulties, it bridges the gap between Beethoven’s middle and late periods.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 26 in E-Flat Major, Op. 81a, “Les adieux” – I. Das Lebewohl: Adagio – Allegro (Murray Perahia, piano)

Late Period:

Ludwig van Beethoven © coloradosymphony.org

The ‘Hammerklavier’ (Op. 106), with its infamous and perilously daring grand leap of an octave and a half at the opening (which, of course, should be played with one hand!); its slow movement of infinite sadness and great suffering; its finale, a finger-twisting fugue, the cumulative effect of which is overwhelming: an expression of huge power and logic.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 29 in B-Flat Major, Op. 106, “Hammerklavier” – I. Allegro (Emil Gilels, piano)

The Last Sonatas (Opp. 109, 110, 111) are considered to be some of the most profoundly philosophical music, music which “puts us in touch with something we know about ourselves that we might otherwise struggle to find words to describe” (Britsh pianist Paul Lewis), which speaks of shared values, and what it is to be a sentient, thinking human being. From the memorable, lyrical opening of the Op. 109 to the final fugue, that most life-affirming and solid of musical devices, of the Op 110, that paean of praise, to the “ethereal halo” that is contained in some of the writing of the Arietta of the Op. 111, the message and intent of this music is clear. And this is Beethoven’s great skill throughout the entire cycle of his piano sonatas.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 30 in E Major, Op. 109 – I. Vivace ma non troppo (Paul Lewis, piano)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 31 in A-Flat Major, Op. 110 – III. Adagio ma non troppo – Fuga: Allegro, ma non troppo – L’istesso tempo di Arioso – L’istesso tempo di Fuga – Meno allegro (Piotr Anderszewski, piano)

What is the Attraction of Performing a Beethoven Sonata Cycle?

So, what is the attraction of performing a Beethoven Sonata Cycle? Glance through concert programmes around the world and it is clear that these sonatas continue to fascinate performers and audiences alike, and no sooner has one series ended than another begins, or overlaps with another. Playing the Sonatas in a cycle is the pianistic equivalent of reading Shakespeare, Plato, or Dante, and for the performer, it offers the chance to get right to the heart of the music, peeling back the layers on a continuous journey of discovery, always finding something new behind the familiar. One does not have favourites; just as when one has children, one should never have favourites, though certain sonatas will have a special resonance. The sonatas are like a family, they all belong together – and they are needed, ready to be rediscovered by each new generation. You can play the sonatas for over a quarter of a century, half a century, and yet there are still many things in these wonderful works to be explored and understood, things which still have the power to surprise and fascinate.

Every pianist worth his or her salt knows that presenting a Beethoven sonata cycle represents a pinnacle in one’s artistic career, but even when a cycle is complete, one cannot truly say one has conquered the highest Himalayan peak. And that is what is so special about this music: you can never truly say you have “arrived” with it, while its endless scope continues to reward, inspire and fulfil.

Further reading

Playing the Beethoven Piano Sonatas – Robert Taub

The Beethoven Sonatas and the Creative Experience – Kenneth Drake

Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas: A Short Companion – Charles Rosen. A very readable analysis of all 32 sonatas by respected pianist and writer

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Shakespeare is not as great as a common opinion used to consider about this author. Rather like Moliere or Dostoyevski.