One of the greatest concert and opera conductors of the 20th century, George Szell was a child prodigy. Educated in Vienna, Szell made his conducting debut at the age of 16 with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, and he was appointed by Richard Strauss to the staff of the Berlin State Opera in 1915. His most significant accomplishment was as musical director of the Cleveland Orchestra, as he raised a respected second-tier ensemble to one of the very best orchestras on the planet.

George Szell Rehearses Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5

From Budapest to Vienna

George Szell

György Endre Szél was born in the afternoon of 7 June 1897 in Budapest as the only child of Kálman and Malvin Szél. Kálman took the family to Vienna after the turn of the century, and he established the city’s first security-guard firm. This pioneering venture held a virtual monopoly in a rapidly expanding city, and Kálman was eager to elevate his family’s status. He converted to Catholicism, and added a second “l” to the family name to suggest a more aristocratic origin.

Karl Szell, as he now called himself, had an enormous passion for opera. Already as a student, he had travelled to London to hear a favourite opera or two, and he constantly attended operas and concerts in Vienna. Young George, later in life, remembered attending his first opera. “I was taken to a performance of Carmen and I had to be taken home after the second act because I was so bored.” Mind you, he was only six at that time.

George Szell Conducts Strauss’ Metamorphosen

Young Prodigy

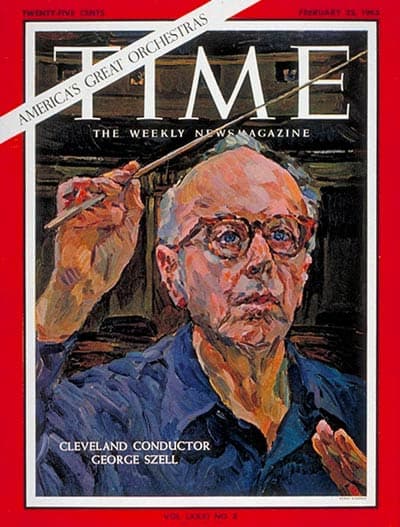

George Szell featured on the Time Magazine cover, 1963

Young Georg amazed his parents at an early age. He began talking at the age of nine months and was soon correctly humming songs he’d heard. By the age of two, he could sing folk songs in Hungarian, German, French, and Czech, and he would slap his mother’s hands if she played a wrong note on the piano. By the age of 5, he knew all the rudiments of music, and as his mother remembers, “he could read almost any kind of music and also improvised and composed.”

His parents, recognising the enormous talents of their son, took him to the most famous piano teacher in Vienna, Theodor Leschetizky. However, Leschetizky was not interested in another child prodigy, nor did he think young Georg was talented enough. By sheer coincidence, Georg began his formal music training as a pianist with Richard Robert, the teacher of Rudolf Serkin. Robert had no routine or system to teach his students, but according to a biographer “he was a shrewd judge of musical potential with incomparable energy in imparting his students with the essentials of musical training.”

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 3 in F Major, Op. 90 – III. Poco allegretto (Cleveland Orchestra; George Szell, cond.)

First Concert Tour

George Szell and Cleveland Orchestra in Leningrad

Szell’s education was supplemented with lessons from prominent teachers of composition and theory, among them the Brahms scholar Eusebius Mandyczewski and Max Reger. Apparently, Szell did not enjoy his lessons with Reger, but he gave his public debut at the age of ten-and-a-half on 30 January 1908 at the Vienna Musikverein. Julius Korngold was in the audience and wrote, “Szell’s piano playing has the soul and expression of a musically mature pianist.”

Szell’s debut caused such a sensation that his parents received countless offers for public appearances of their son. Dubbed “the new Mozart,” his parents permitted one concert tour of the most prestigious musical centres, London, Berlin, Dresden, Cologne, Hamburg, and Leipzig. For his London concert, Szell played Mendelsohn’s Capriccio in B minor, several solo pieces of Chopin, and as an encore, his own Aria e Polacca. That concert also included an overture composed by Szell.

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 8 in C Minor, WAB 108 (1890 edition, ed. L. Nowak) – I. Allegro moderato (Cleveland Orchestra; George Szell, cond.)

The Adolescent Prodigy

George Szell in Tokyo, 1970

A London reporter relates a humorous anecdote. “When I asked him to improvise at the piano, the boy insisted that I give him a theme. Immediately his face grew serious at once, as if another personality was taking possession of him.” Is this for piano only, or for orchestra? asked the reporter. For orchestra, said the boy, “I am hearing all the instruments.” And then this wonderful child played, played, and as his fingers wandered over the keyboard, then striking with great power, then touching it with incredible lightness, he whispered Horns, Cello solo, all the strings, full orchestra…”

As his interest in the orchestra grew stronger, his desire for composing and performing as a pianist diminished. While playing orchestral scores at the piano became a lifelong hobby, he probably recognised that “I would not fulfil the promise of my early compositional talents, as I wasn’t good enough by my own standards.” Although Szell continued to take engagements as a pianist and kept writing his own music, “around the age of twelve or thirteen, it was pretty clear that eventually I would become a conductor.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter