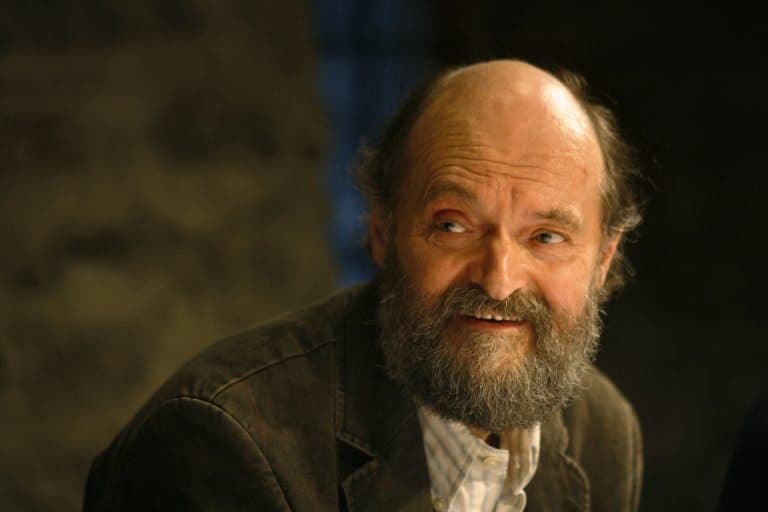

Estonian-born composer Arvo Pärt (1935- ) has managed to strike a sound of devotional archaism into a world of chaotic modernity. Highly experimental during his early musical career, Part’s study of early music inspired a new, and completely unique musical language and vocabulary.

Arvo Pärt

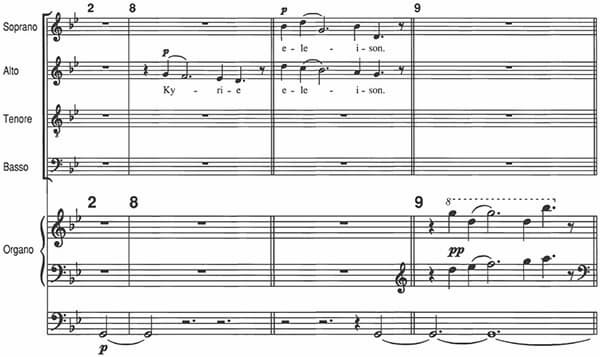

Influenced by Orthodox Russian intonations, medieval heterophony, and Renaissance polyphony, his music acquired a deeply mystical character via a technique the composer calls “tintinnabuli.” That name derives from the bell-like resemblance of notes in a triad, and involves a melodic voice that moves by steps around a central pitch, with the tintinnabuli voice simultaneously sounding the notes of the tonic triad.

Arvo Pärt: Berliner Messe, “Kyrie” (Theatre of Voices; Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, organ; Paul Hillier, cond.)

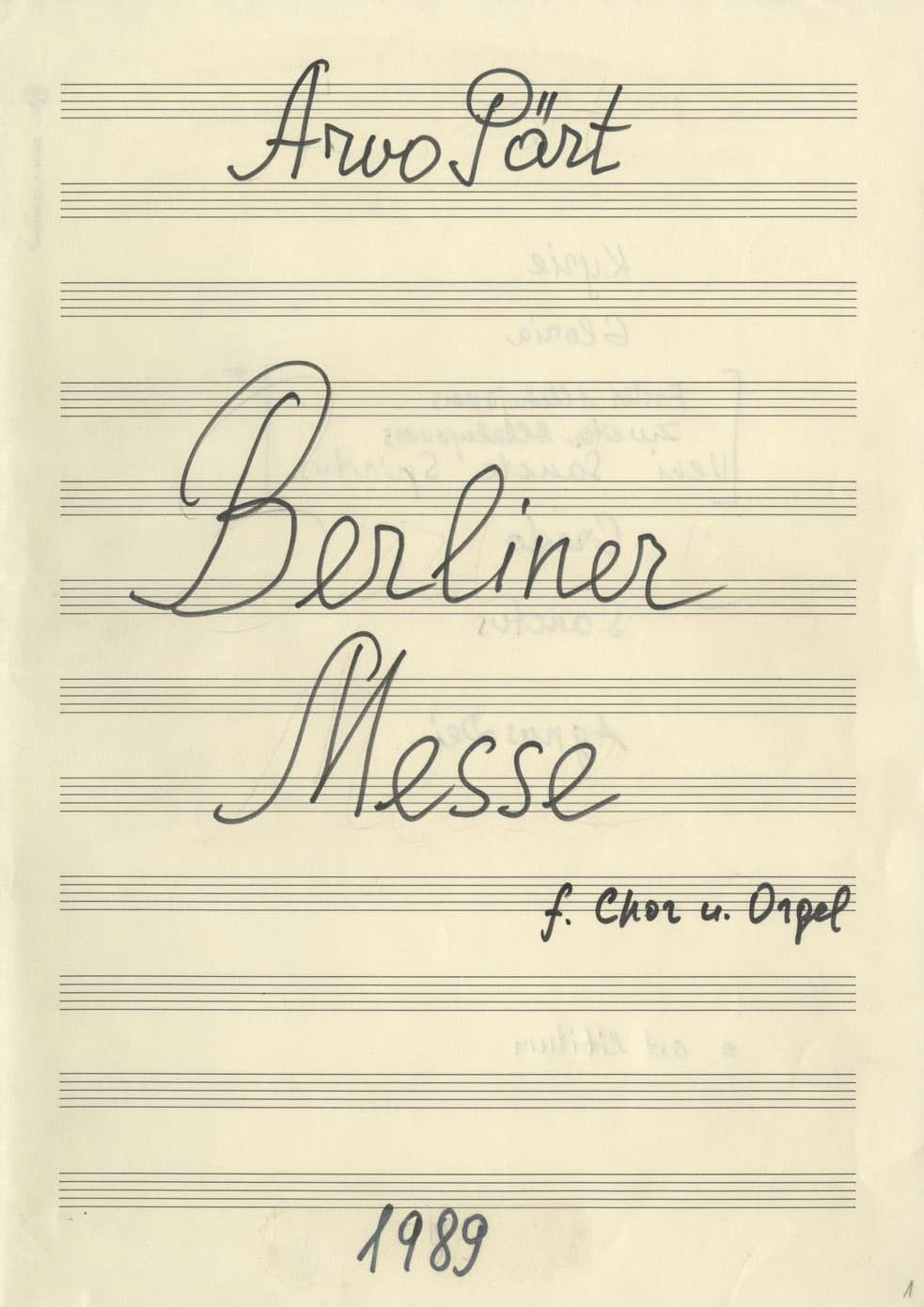

Arvo Pärt’s Berliner Messe

The relationship between these two voices follows a predetermined scheme, which varies in detail from work to work. “The whole secret of tintinnabuli,” according to Pärt, “lays in the two lines. One line is who we are, and the other line is who is holding and taking care of us. Sometimes I say that the melodic line is our reality, our sins. But the other line is forgiving the sins.” The apparent simplicity of its materials draws together the emotional, musical, and spiritual aspects of his personality, and creates a soundscape that has been criticized as “sentimental holy minimalism.” However, his music has clearly a slightly different meaning for each listener, and while it sounds ancient and modern at the same time, it communicates the spiritual and mystical power that Pärt sees as music’s essential purpose.

Arvo Pärt: Berliner Messe, “Gloria” (Theatre of Voices; Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, organ; Paul Hillier, cond.)

Shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989, Pärt was commissioned to compose a mass for the 90th Katholikentag, a festival-like gathering in German-speaking countries organized by the laity of the Catholic Church. Paul Hillier conducted the premiere performance on 24 May 1990 during the liturgical Feast of Ascension at St. Hedwig’s Cathedral in East Berlin. Originally scored and performed by four soloists and organ, Pärt later arranged the work for chorus and string orchestra. Pärt explained, “tintinnabulation is an area I sometimes wander into when I am searching for answers, in my life, my music, my work. In my dark hours, I have a certain feeling that everything outside this one thing has no meaning. The complex and many-faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity.”

Arvo Pärt: Berliner Messe, “Alleluia Verse I” (Theatre of Voices; Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, organ; Paul Hillier, cond.)

Organ of the Hedwig’s Cathedral in Berlin

When Pärt arrived in the West in 1980, he appeared “like an apparition from another world. He looked like a strange saint, a mystic, a medieval monk, and that’s exactly what his music sounded like.” As a biographer writes, “it seemed that no one on the Western music scene could imagine an artist not wanting to play some kind of role, or of having no interest in image and prestige.” Pärt was clearly looking for something else, as he visualized man freed from all idiosyncrasies and inequalities, strengths and weaknesses, right down to the core of his being. “At this depth, we are all so similar that we could recognize ourselves in each other.”

Arvo Pärt: Berliner Messe, “Alleluia Verse II” (Theatre of Voices; Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, organ; Paul Hillier, cond.)

The Berlin Mass is Part’s setting of the five-part Ordinary of the mass, to which he added two Alleluia verses and the Pentecost sequence Veni Sancte Spiritus. The two added Alleluia chants make the Mass suitable for performance at Christmas. The work is undoubtedly intended for Catholic worship, with all its flexibility in the church year, “but is of course equally at home in the ideological neutrality of the concert hall.” Pärt associates the scale passages as “things mortal and carnal, like temptation, sin, and death.” The tintinnabuli voice and its triadic purity, however, suggest “divine connotations, redemption, immortality, and godliness.” The combination of the two voices has been described as “creating an atmosphere of absolute harmonic stability filled with colorful and irregular dissonances.”

Arvo Pärt: Berliner Messe, “Veni Sancte Spiritus” (Theatre of Voices; Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, organ; Paul Hillier, cond.)

Arvo Pärt’s Berliner Messe “Kyrie”

For a number of writers, Pärt’s inherent musical religiosity and symbolism are most striking in the Pentecostal sequence, “Veni Sancte Spiritus.” As a critic writes, “The texture is extremely sheer, as it consists entirely of duets. Its translucence is enhanced by the very sparse participation of the scale voice within each of the duet passages. Moreover, the tintinnabuli voice seems to mimic the ethereal sonority of the other voice, eschewing its usual scalar figures in favor of a nearly triadic motion by leap. Recalling the biblical account of the Pentecost, the mortal voice seems to aspire to the divine, possibly pointing to the paradox of Christ’s essential humanity and divinity.”

Arvo Pärt: Berliner Messe, “Credo” (Theatre of Voices; Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, organ; Paul Hillier, cond.)

Although a single line, Pärt uses tintinnabuli the way Johann Sebastian Bach uses traditional tonality to imply harmony: linearly. That is, a single, linear musical line will contain enough elements to create a sense of harmony, or in this case, a sense of tintinnabuli. For Pärt, the “Credo” text was very familiar as he had set it twice before. However similar the settings might be, it is difficult to ignore the difference of context. His earlier setting, while under the totalitarian rule of the Soviet Union, is a somber setting in the minor key, while the “Credo” in the Berlin Mass is a joyous setting in the major key.

Arvo Pärt: Berliner Messe, “Sanctus” (Theatre of Voices; Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, organ; Paul Hillier, cond.)

The “Sanctus” is inward looking, with the sopranos wholly absent from the movement, and the concluding “Agnus Dei” uses an assortment of new and previously introduced techniques. We find canonic devices, compound tintinnabuli, and a determined meter based on the text. The Berliner Messe ends in a mood of calm, and with a great sense of detachment. Here as elsewhere, Pärt was looking to liberate music from the ballast of times, epochs, and styles. As he writes, “I am looking for a common denominator. I am striving for a music that I could call universal.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Arvo Pärt: Berliner Messe, “Agnus Dei” (Theatre of Voices; Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, organ; Paul Hillier, cond.)