Eleanor Cory: O’Keeffe’s Flora

Starting in the mid-1920s, American artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) started her 30-year exploration of flowers. By taking something that might be quite small and painting it multiplied by many times, she found a way to make a statement in nature and in colour that created a new perception of a common object.

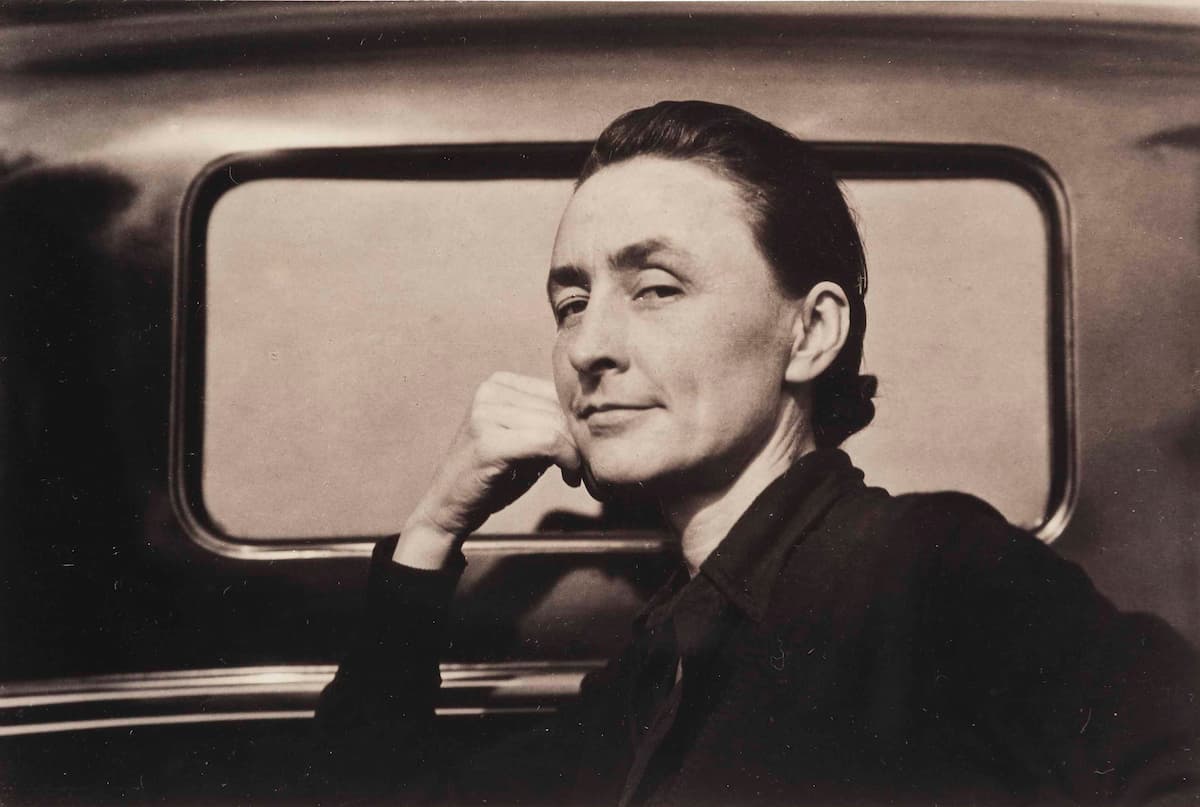

Alfred Stieglitz: Georgia O’Keeffe: After Return from New Mexico, 1929 (Georgia O’Keeffe Museum)

For her, it was a way of stopping time, making the viewer look at something they generally saw but never looked at in detail. From her studies in photography and her work with modernist techniques such as close-cropping, O’Keeffe took otherwise small objects and made important statements in graphic design.

What saddened her was the male view that all of these flowers were really about sex and she fought a long battle for them to be seen as what they were: flowers. In her opinion, viewing her paintings solely as a representation of female sexual anatomy limited the ‘key significance and meaning of her work.’

Her ability to take a regular object and make it the focus for patterns of colour, shade, and line was recognized already by the late 1920s. As she drew her flowers, they became larger and more simple.

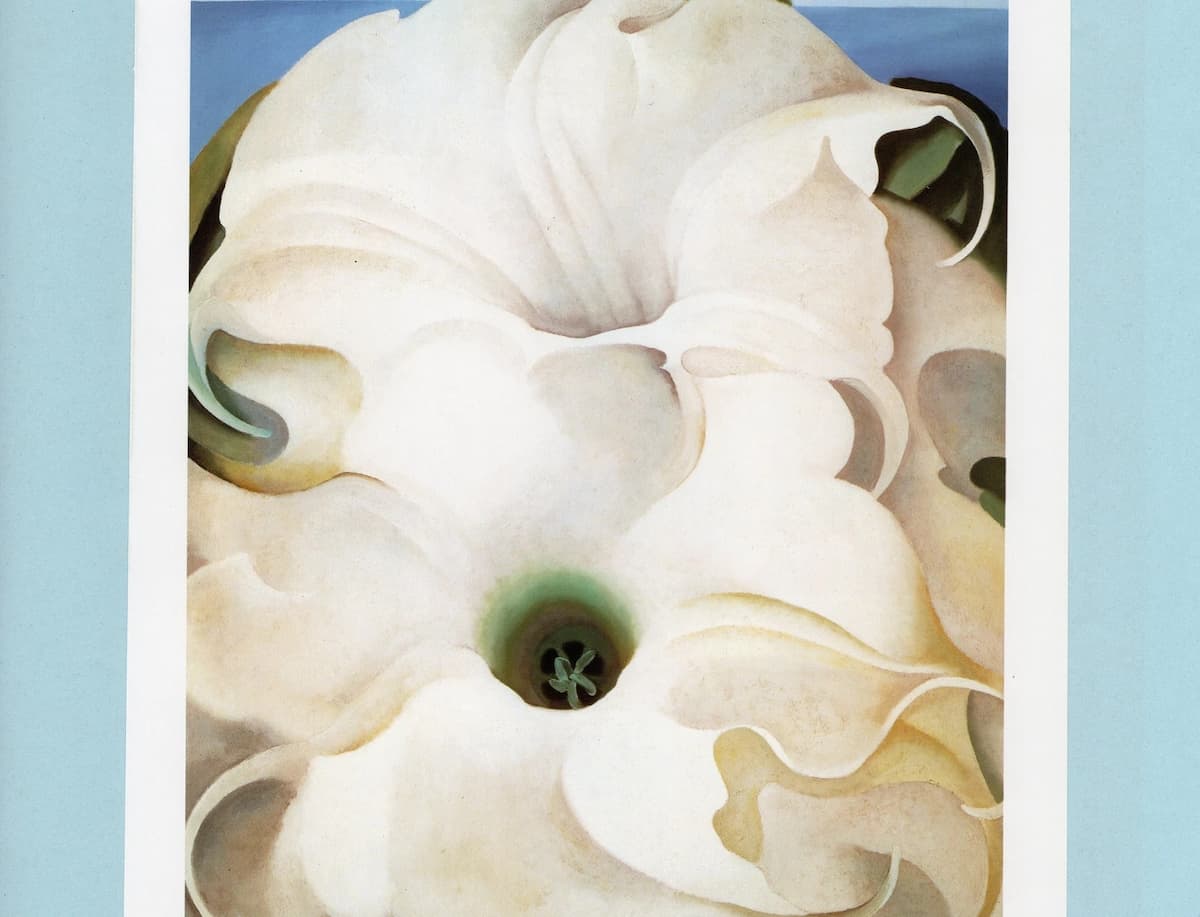

In the mid-1960s, O’Keeffe was taking pictures of jimson weed flowers. These flowers of the poisonous datura tree whirl out from the centre to curled points.

Open flower of Datura stramonium (Jimson Weed). Photo by Saara Nafici. (Brooklyn Botanic Garden

In her painting, O’Keeffe juxtaposed two flowers and made the central stamen the centre of a dark greenness. The leaves curl more wildly and the curled points are more exaggerated. By focusing so closely that the entire flower is not visible, O’Keeffe shifts our focus to the shades of white, not to the overall shape of the flower.

O’Keeffe: Two Jimson Weeds / Two Datura / Bella Donna (various titles) (Georgia O‘Keeffe Museum)

American composer Eleanor Cory (b. 1943), in her work O’Keeffe’s Flora, based it upon three of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings: jimson weed, jack-in-pulpit, and red poppy. The first movement, Two Jimson Weeds, takes up the swirly imagery of the flowers.

Eleanor Cory: O’Keeffe’s Flora – I. Two Jimson Weeds (North-South Chamber Orchestra; Max Lifchitz, cond.)

Eleanor Cory

Cory’s second movement is entitled Jack-in-the-Pulpit V and refers to O’Keeffe’s 1930 painting Jack-in-Pulpit Abstraction, No. 5. The vertical painting is filled with sinuous forms that ascend from the bottom to take definition at the top. At the back, light comes from a single white line that lights the back right of the painting. In 1930, O’Keeffe made six versions of this flower, each iteration simpler than the last.

O’Keefe: Jack-in-Pulpit Abstraction, No. 5, 1930 (National Gallery of Art)

Eleanor Cory: O’Keeffe’s Flora – II. Jack-in-the-Pulpit V (North-South Chamber Orchestra; Max Lifchitz, cond.)

The final movement is one of O’Keeffe’s most brilliant paintings, Red Poppy from 1927. The flower fills the entire frame, done in shades of red with a black centre. A yellow highlight at the back right almost makes you think you’re looking over mountains into a valley. The size and magnification of the flower make it difficult to take in as a single image.

Georgia O’Keeffe. Red Poppy, 1927. Private collection

Cory’s Red Poppy captures the bright happiness of the red petals, seeming to slip down the curved surface to the dark centre.

Eleanor Cory: O’Keeffe’s Flora – III. Red Poppy (North-South Chamber Orchestra; Max Lifchitz, cond.)

O’Keeffe’s paintings were innovative for their focus on the natural world in a way that was more familiar from the new techniques of photography. By using as her source, a work of beauty that was rarely examined in detail, flowers, she made her viewers re-examine the world around them. In putting these works to music, Cory has the same effect of placing us in the middle of the image and exploring the motions inherent in the painting.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter