Although he was overshadowed during his lifetime by his more flamboyant colleague Jean-Baptiste Lully, Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643-1704) is today acknowledged as one of the most gifted and versatile French composers. His most famous work, the main theme from the prelude of his Te Deum, is still used as a fanfare during television broadcasts of the Eurovision Network and the European Broadcasting Union.

Marc-Antoine Charpentier: Te Deum, “Marche en Rondeau”

Enigmatic Self-Assessment

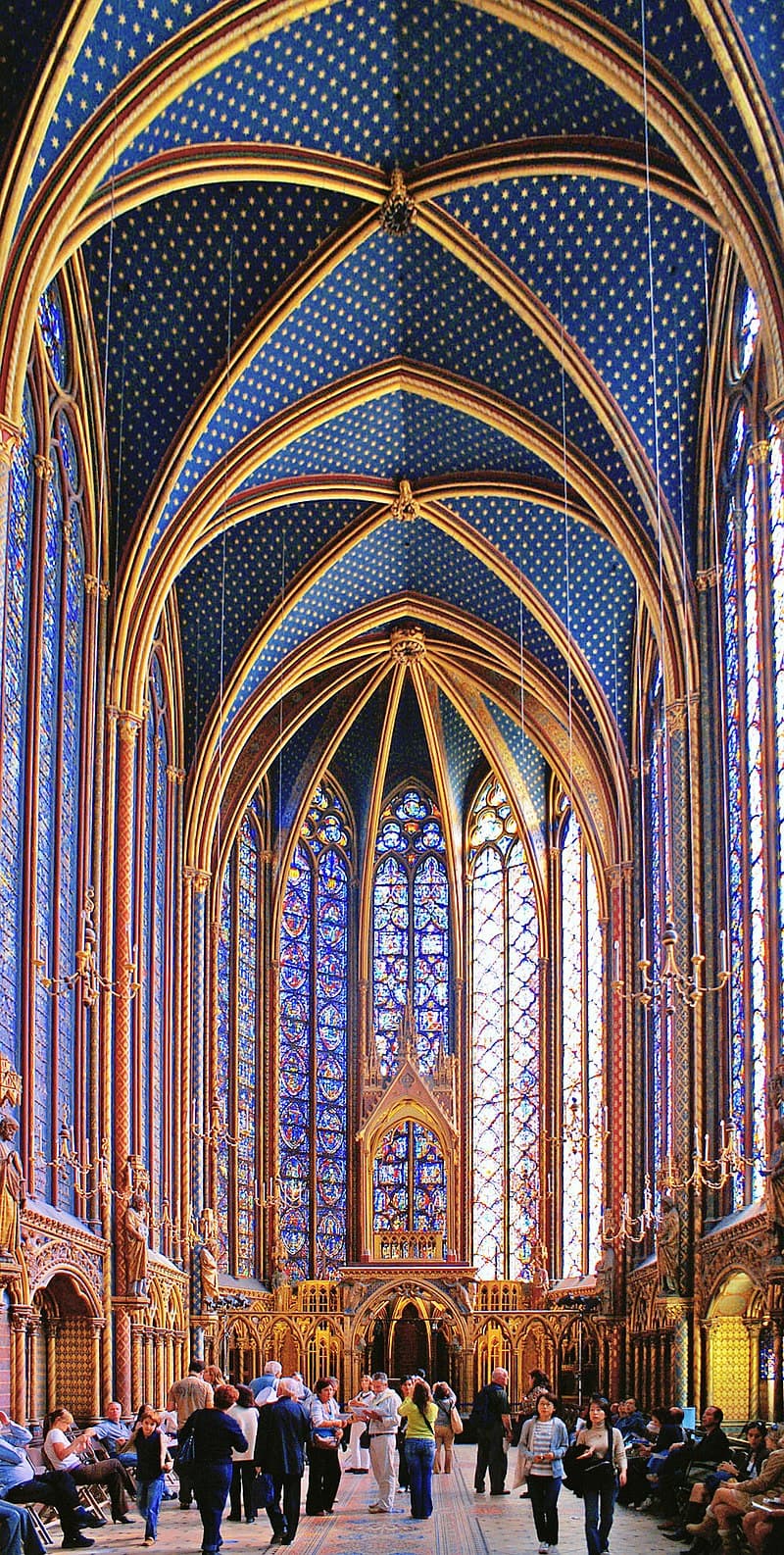

Marc-Antoine Charpentier died at Sainte-Chapelle, Paris, on 24 February 1704. He was buried in a little walled-in cemetery just behind the choir of the chapel, but the grave’s location is unknown as the cemetery no longer exists. For posterity, he left an enigmatic and semi-sacred dramatic cantata to a Latin text. This text finds the “ghost” of Charpentier speaking to two wanderers in the underworld.

Marc-Antoine Charpentier

“I was a musician,” he writes, “considered good by the good ones, scorned as ignorant by the ignorant. And since those who scorned me were much more numerous than those who lauded me, music became to me a small honour and a heavy burden. And just as at my birth I brought nothing into this world, I took nothing from it at my death.”

Marc-Antoine Charpentier: Canticum in honorem Beatae Virginis Mariae (Convivium Vocale Gothenburg)

To Posterity

The music of Charpentier was not really published during his lifetime. Some smaller works did appear in print, issued by the music publisher Christophe Ballard, who enjoyed a royal monopoly. Since Charpentier never held a position at the court of Louis XIV, his opportunities for wider recognition were somewhat limited.

Sainte-Chapelle, Paris

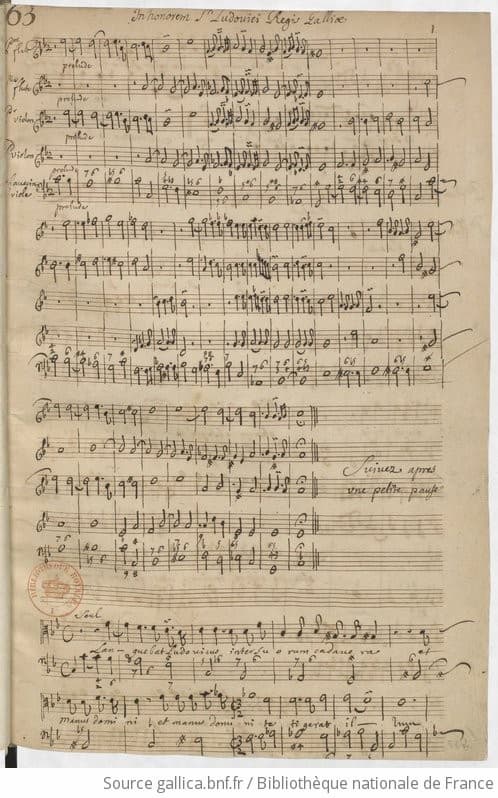

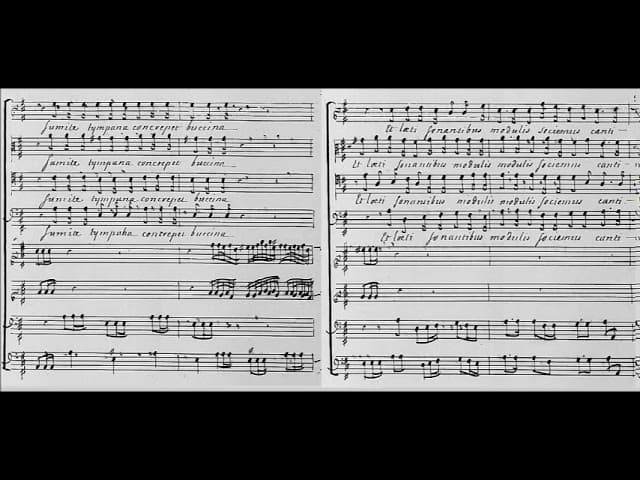

We are fortunate, however, that Charpentier was a meticulous caretaker of his manuscripts. According to scholars, “they were carefully written in ink and gathered in numbered sheafs, and later compiled into 28 autograph volumes.” As such, he classified more than 500 of his compositions. Charpentier left the collection to his nephew Jacques Edouard, a printer and bookseller. He published a small collection of motets, but as he failed to find a private buyer for his uncle’s manuscripts, he placed them in the King’s library in 1727.

Marc-Antoine Charpentier: Médée (Véronique Gens, soprano; Cyrille Dubois, tenor; Judith van Wanroij, soprano; Thomas Dolié, baritone; David Witczak, bass; Hélène Carpentier, soprano; Adrien Fournaison, bass-baritone; Floriane Hasler, mezzo-soprano; David Tricou, counter-tenor; Fabien Hyon, tenor; Jehanne Amzal, vocals; Marine Lafdal-Franc, soprano; Concert Spirituel Chorus; Concert Sprituel Orchestra; Hervé Niquet, cond.)

Mélanges

Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s autograph

This particular collection, called “Mélanges,” is one of the most comprehensive sets of musical autograph manuscripts of all time. Since Charpentier was in the service of the very devout Mademoiselle de Guise, he composed a large number of religious works in a wide variety of genres. This includes 11 mass settings and 140 liturgical works, roughly 207 motets and about 30 instrumental ensemble compositions for church use.

In “Mélanges” researcher have found almost “every category of sacred music in great diversity and individual works in length, number of performers required, compositional techniques and forms.” It has been suggested that the most original and perhaps influential works are the “Tenebrae” compositions for Holy Week. These works apparently initiate a distinctive French style of genre, “culminating in the works of François Couperin.

Marc-Antoine Charpentier: “Tenebrae factae sunt” (István Kovács, bass; Purcell Choir; Orfeo Orchestra; György Vashegyi, cond.)

Comédie-Française

Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s autograph

Charpentier was busy composing for the stage, as about 30 theatre pieces did survive. He wrote overtures, intermèdes, and incidental music for spoken dramas produced by the Comédie-Française, and a series of pastorales, operatic divertissements and tragédies en musique for various places and patrons. He initially worked and collaborated with Molière and subsequently with Thomas Corneille.

His two most amusing entertainments, “Les arts florissants” and “Les Plaisir de Versailles,” unfold in a single act and several scenes and are both allegorical fantasies dealing with the arts in which music plays a leading role. The highlights of his operatic involvements are three massive “tragédies lyriques,” including his masterwork Médée. While the characterization of the heroine as lover, mother, jealous wife, furious and malignant sorceress is remarkable, his music “provides a synthesis of warmly italiante vocalism and precise French declamation.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter