On 22 December 1808, Ludwig van Beethoven invited audiences to a benefit concert at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna. One of the most remarkable events of Beethoven’s career, the concert saw the public premieres of his Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, the premiere of the Fourth Piano Concerto, and the Choral Fantasy. The event also featured various hymns and arias, a movement from the C-major Mass, and a bit of piano improvisation by Beethoven himself.

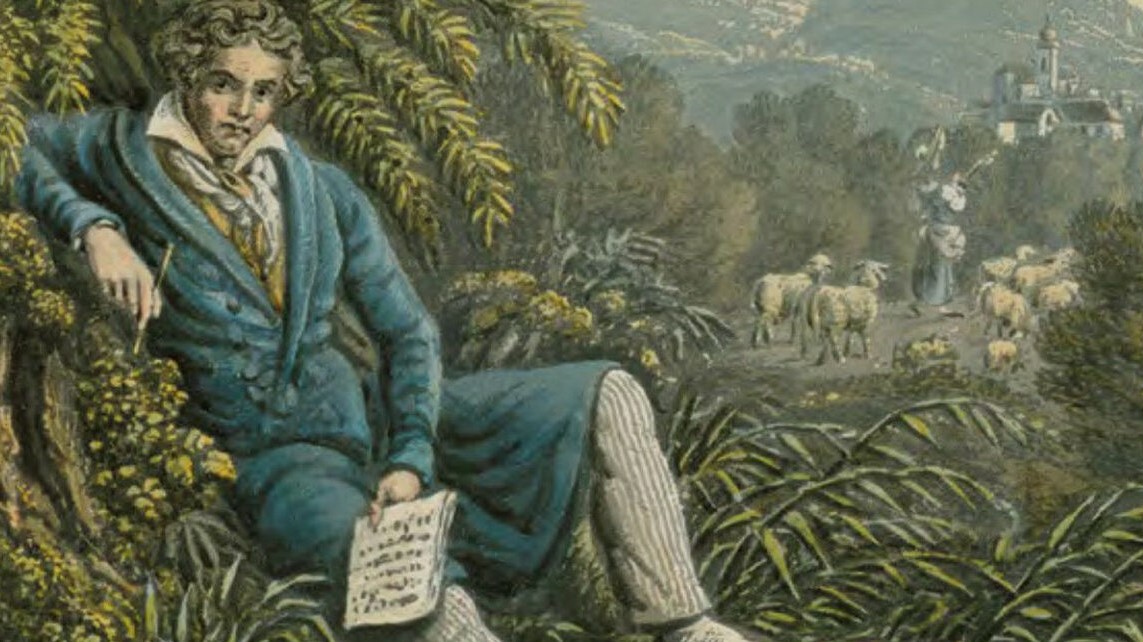

Beethoven at the Brook by Franz Hegi © Beethoven Haus Bonn

The composer Friedrich Reichardt sat in the audience and reported, “in the bitterest cold, from half past six to half past ten, we experienced the truth that one can easily have too much of a good thing, and still more of a loud thing.” According to various reports, this marathon concert was seriously under-rehearsed and not a great success.

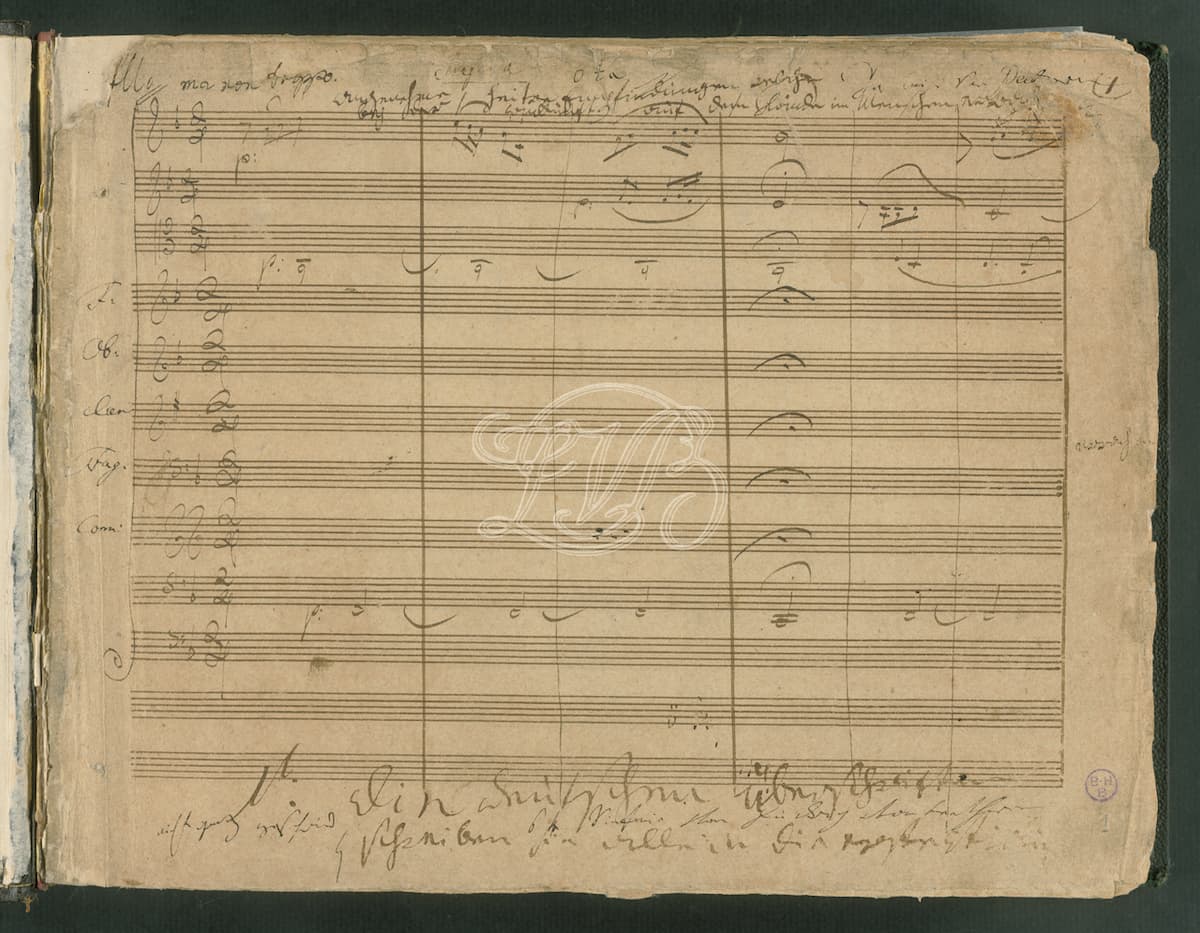

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6, Op. 68 “Pastoral” (Allegro ma non troppo)

It often comes as a surprise that Beethoven wrote his Fifth and Sixth symphonies at roughly the same time. Composed primarily during the spring and autumn of 1808, both works are dedicated to Count Razumovsky and Prince Lobkowitz, and they were published within weeks of one another in the spring of 1809.

Circumstances of genesis, premier performance, and publication aside, both symphonies are experiments in symphonic extremity as they push completely different musical boundaries to their limits and beyond. Drawing upon the well-established genre of the programmatic symphony, the enormously popular “Pastoral” creates a musical universe where gentle repetitions and the imitation of nature define the structure on a small and large scale.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6, Op. 68 “Pastoral” (Andante molto mosso)

Beethoven described the “Pastoral Symphony,” as more an “expression of feeling than painting.” He liked nothing more than a walk in the woods, jotting down musical ideas in a miniature sketchbook he always carried in his pocket. “No one,” he wrote to Therese Malfati, “can love the country as much as I do. For surely woods, trees, and rocks produce the echo which man desires to hear.”

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6, first movement

Beethoven’s friend and biographer Anton Schindler recounts a walk he took with the composer in April 1823 in the countryside around Vienna. “Passing through the pleasant meadow valley between Heiligenstadt and Grinzing, which is traversed by a gently murmuring brook that hurries down from a nearby mountain and is bordered with high elms, Beethoven repeatedly stopped and let his glances roam, full of happiness, over the glorious landscape. ‘Here I composed the Scene by the Brook,’ Beethoven said, and the yellowhammers up there, the quails, nightingales, and cuckoos around about, composed with me.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6, Op. 68 “Pastoral” (Allegro)

Although Schindler might have embellished or even invented this little anecdote, Beethoven does mark the birdsongs in the score. In the instrumental cadenza at the close of the “Scene by the Brook,” the nightingale is the flute, the quail is the oboe, and the unison clarinets represent the cuckoo. The music is clearly pictorial in its description, but above all, it aims to evoke the feeling of being back in the countryside after way too much time spent in the city.

Joseph Franz Maximilian, 7th Prince of Lobkowitz

Beethoven’s programmatic intent is clearly expressed in the suggestive title of the work “Pastoral Symphony,” or “Recollections of Country Life,” and also in imaginative headings for individual movements. The opening “Allegro ma non troppo” (Awakening of cheerful feelings upon arriving in the country) quietly evokes images of pastoral bliss. An open drone in the bass gives rise to a bright and leisurely unfolding theme and its thematic continuation. The extraordinary development section is based on incessant repetitions of fragmented variants of the open subject.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6, Op. 68 “Pastoral” (Allegro)

Set in almost complete harmonic stasis, this sunny movement eventually concludes with a jovial coda. The second movement, “Scene by the Brook,” famously includes the onomatopoeic birdcalls. In fact, the birds bring the gently babbling brook to a complete standstill and engage in a quasi-cadenza, with the nightingale providing the final obligatory trill. The “Merry gathering of peasants” in the third movement—basically a rustic peasant dance—is rudely interrupted by a “Tempest storm.”

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony manuscript

The entire orchestra surges and shakes to emphasize the heavy rain, and the timpani provides the rolling thunder. “It is no longer merely a wind and rainstorm,” writes Berlioz, “it is a frightful cataclysm, the universal deluge, the end of the world.” Without pause, the music progresses into the concluding “Allegretto,” (Shepherd’s hymn—Happy and thankful feelings after the storm.) The Shepherds yodel happily in the clarinets, and a richly scored hymn of thanksgiving concludes a symphony that simultaneously functions on descriptive and expressive levels.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter