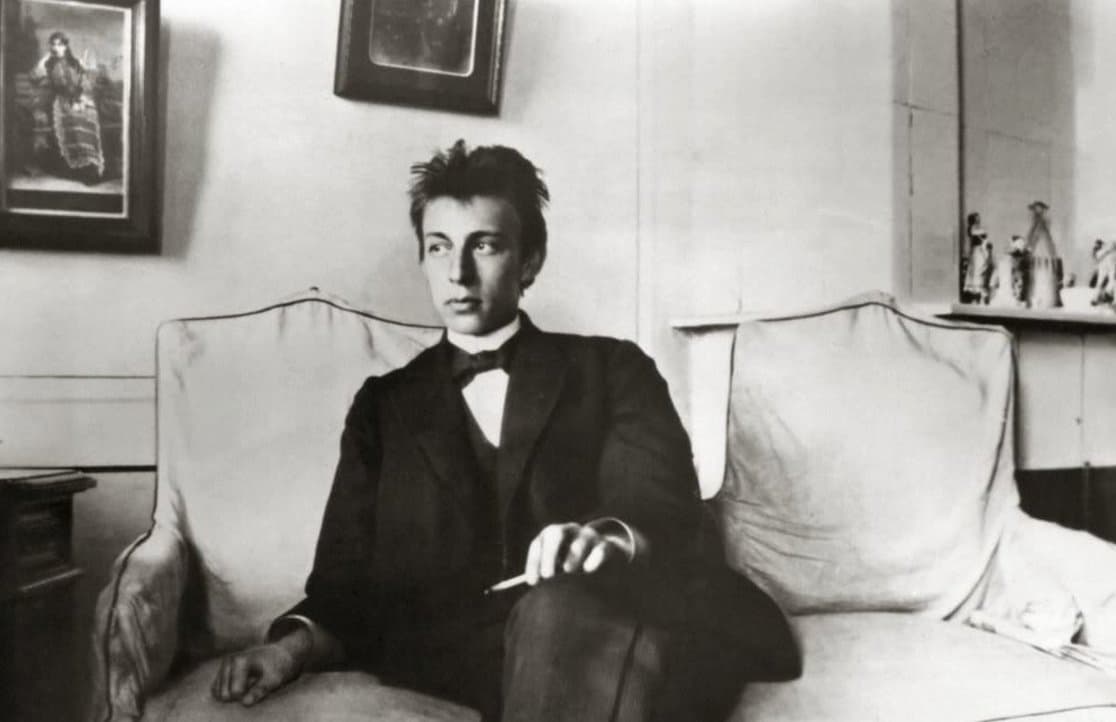

The Buddying Composer

The young Rachmaninoff

Sergei Rachmaninoff made his first tentative attempts at composition during the summer of 1886. The resulting piano piece is unfortunately now lost, but his piano-duet transcription of Tchaikovsky’s Manfred Symphony was later played to Rachmaninoff’s “musical hero.”

“To Tchaikovsky,” Rachmaninoff writes, “I owe the first and possibly the deciding success in my life. He was, at that time, already world famous and honoured by everybody, but he remained unspoiled. He was one of the most charming artists and men I ever met.”

It was becoming exceedingly clear that the piano was at the centre of his musical creativity. The early piano pieces of 1887 “reveal the extraordinary sense of kinship he felt with the instrument.” As he was starting his 1888 autumn term at the Moscow Conservatory, his cousin Alexander Siloti became his new piano teacher, and Rachmaninoff’s pianistic progress was truly astonishing.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 1 “Vivace” (Boris Giltburg, piano; Brussels Philharmonic; Vassily Sinaisky, cond.)

Conflict of Interest

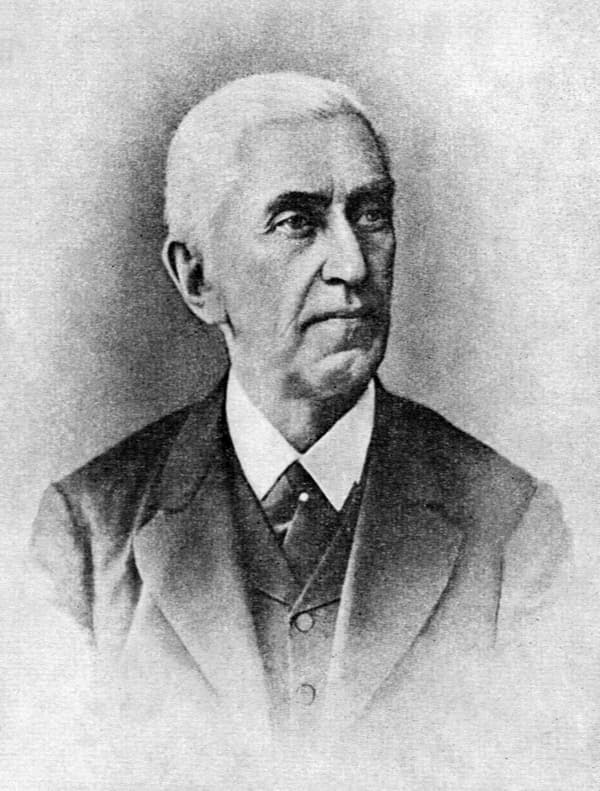

Nikolai Zverev.

Rachmaninoff, however, was increasingly drawn to composition, but that decision started to create problems with the notoriously inflexible Nikolai Zverev. According to a contemporary report, a heated exchange took place in 1889 when Zverev raised a fist to his student. That gesture resulted in a total breakdown of relations, and although Rachmaninoff tried to make amends, Zverev simply ignored him.

Things got bad enough that Rachmaninoff, who had been lodging with Zverev, moved in with his aunt Vavara Satina and her two young daughters. They spend their summers on the Satin estate at Ivanovka, which later became Rachmaninoff’s home. As the composer wrote in his memoires, “This estate resembled a boundless ocean, where the waves are endless fields of wheat, rye, and oats, stretching as far as the eye can see.”

During the summer months at Ivanovka, Rachmaninoff began work on his largest and most important composition to date, the First Piano Concerto, Op. 1. However, there was trouble at the Conservatory as his teacher Alexander Siloti vehemently disagreed with the dictatorial methods of the new Director Vasily Safanov. Siloti resigned, and Rachmaninoff had to choose between accepting a change of piano teacher, or taking his piano finals one year early.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 1 “Andante” (Stephen Hough, piano; Dallas Symphony Orchestra; Andrew Litton, cond.)

Opus 1

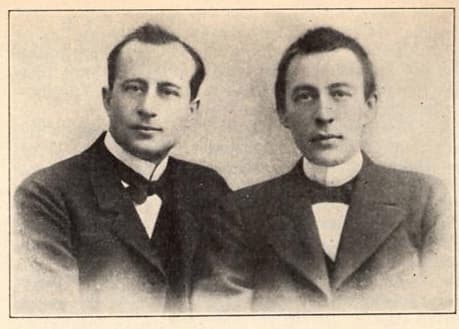

Alexander Siloti

In a mere three weeks, Rachmaninoff prepared the Chopin B-minor Sonata first movement and Beethoven’s “Appassionata” for examination and graduated with honours. Alexander Goldenweiser recalled Rachmaninoff’s prodigious pianistic talent. “His talent surpassed any other in my experience, almost unbelievable. He memorised new pieces at an almost unprecedented rate.”

After his successful examination, Rachmaninoff travelled with Siloti to Ivanovka, where he composed the remaining movements of his First Piano Concerto in a mere two and a half days. As he wrote to Natalya Skalon on 26 March 1891, “I am now composing a piano concerto. Two movements are already written; the last movement is not written, but is composed; I shall probably finish the whole concerto by the summer, and then in the summer orchestrate it.”

Actually, this had been his second attempt at a piano concerto, as he had earlier abandoned a concerto in C minor. In the event, Rachmaninoff performed the first movement of the concerto at a student concert on 17 March 1892 at the Moscow Conservatoire, with the composer as soloist and Vasily Safonov conducting.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 1 “Allegro vivace” (Yuja Wang, piano; Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

Original vs Revision

Alexander Siloti and Sergei Rachmaninoff

A scholar wrote, “this may have been the only time the composer played the concerto in its original form, although Siloti, to whom it is dedicated, programmed it to play himself on several occasions. The work was a demonstration of Rachmaninoff’s extraordinary flair and lyrical instincts. “Listening to this impassioned, brilliant music, articulated by countless individual turns of phrase, it is difficult to credit it as being the work of a mere 19-year-old.”

Vasily Safanov, 1902

Modern audiences, however, are probably mostly familiar with the revised version of 1917. Rachmaninoff had grown increasingly dissatisfied with the original version, and he gave the orchestration greater clarity and tightened the overall structure. Benefitting from his development as a composer, Rachmaninoff thinned the texture in both the orchestral and piano parts, and transformed a work of youthful vivacity into a concise and spirited work.

Rachmaninoff was highly satisfied with his attempt and reports, “I have rewritten my First Concerto; it is really good now. All the youthful freshness is there, and yet it plays itself so much more easily.” For Rachmaninoff, the listening public was already familiar with his Second and Third Concertos, and not really enthusiastic about a work designated as Op. 1. As the composer reports, “Nobody pays any attention to it. When I tell them in America that I will play the First Concerto, they do not protest, but I can see by their faces that they would prefer the Second or Third.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter