Tomaso Albinoni, who according to his death notice dated 17 January 1751, died of diabetes mellitus in Venice, is primarily known for his famous “Adagio in G minor.” No self-respecting collection of Baroque music can do without it. But wait, things are not as simple as they appear. Although the “Adagio” is attributed to Albinoni, it is actually the creation of the mid-20th century Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto.

Tomaso Albinoni

Giazotto was working on a biography of the composer, and he claimed to have found a fragment of an unknown Albinoni composition in a German library. That fragment apparently contained snippets of a melody and a supporting continuo part, and by relying on the stylistic features of the Italian Baroque, Giazotto “completed” the fragment. Always eager to publish freshly discovered masterpieces, the Italian publisher Ricordi issued the “Albinoni Adagio” in 1958. However, until this day, nobody has been able to locate or examine the mysterious Albinoni fragment; the “Adagio” might well be a very clever work of fiction.

Albinoni/Giazotto: “Adagio in G minor”

Albinoni’s Compositions: Operas, Cantatas, Sonatas and More

Music score of Albinoni’s Adagio

To be sure, Tomaso Albinoni was not a fictitious composer. In fact, he was a respected musician and prodigious composer, and the libretto of his penultimate opera Candalide of 1734 describes it as his 80th opera. A scholar writes, “Only 50 or so public operas are known from librettos or the few scores that have survived, but the balance may well have been made up from intermezzos and more intimate stage works for private performance, for which librettos were not published.” In addition, Albinoni composed roughly 50 solo cantatas, and nearly 100 sonatas for “one and six instruments and continuo composed in church, chamber or mixed styles.” Not to be outdone, he also wrote 50 concertos and 8 sinfonias, independently of larger works. The Albinoni scholar Michael Talbot writes, “many attributions to Albinoni in 18th-century sources are doubtful, despite their over-eager endorsement by certain scholars and editors in modern times.”

Tomaso Albinoni: Il nascimento de l’Aurora (June Anderson, soprano; Margarita Zimmermann, mezzo-soprano; Susanne Klare, alto; Sandra Browne, mezzo-soprano; Yoshihisa Yamaji, tenor; Claudio Scimone, cond.; I Solisti Veneti)

Albinoni’s Successful Works

Copper engraving of Italian composers Tomaso Albinoni, Domenico Gizzi and Giuseppe Colla by Pietro Bettelini

Albinoni certainly had his finger on the pulse of his time. Looking to make serious money, he concentrated on writing instrumental music. As he had enjoyed good success with his first collection of trio sonatas, he now addressed a growing musical demand beyond the traditional homes of musical performance, court, and church. A lively secular music scene was developing, “bolstered by professional musicians and a growing number of amateurs. Insatiable demand for new music fostered the development of new genres, amongst them the symphony and the instrumental concerto.” Music publishing was expanding rapidly, and advances in engraving and printing techniques fostered steadily growing competition. Albinoni’s music became known and was valued well beyond Italian borders. His early instrumental works were reissued and reprinted throughout the first three decades of the 18th century, and musical excerpts found their way into contemporary instruction manuals for the violin. And his famous oboe concertos were the first of their kind by an Italian composer to be published.

Tomaso Albinoni: Magnificat in G minor (Marta Szucs, soprano; Klára Takács, alto; Denes Gulyas, tenor; Tamas Bator, bass; Budapest Madrigal Choir; Budapest Strings; Ferenc Szekeres, cond.)

Albinoni’s Influences on Bach

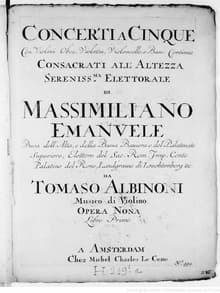

Albinoni’s Concerti Op. 9

After the death of his wife, Albinoni suffered waning popularity and rising physical problems. He completely withdrew from public life, and in 1740, eleven years before his death, a “posthumous” collection of violin concertos was published in France. Albinoni’s reputation has fluctuated, and the general assessments of his music have been harsh as he is “taxed with dryness and lack of harmonic finesse.” To be sure, he does use a number of formal stereotypes, and he seems to have been less concerned with outside influences. Yet, he possessed remarkable melodic gifts, “which kept him in demand as a composer of operas long after the popularity of his contemporaries faded.” Scholars have noted, “Albinoni’s strongest asset is the pronounced individuality of his music. His output may be largely mass-produced, but his ideas are all his own. If the instrumental music seems certain to survive, the same cannot yet be said of his vocal music despite its equal historical importance.” Albinoni was certainly well respected during his lifetime, as J.S. Bach based four of his keyboard fugues on subjects taken from Albinoni’s Op.1. Bach is also known to have used Albinoni’s compositions as teaching material.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Tomaso Albinoni: Oboe Concerto in D minor, Op. 9, No. 2