Marie van Zandt

Brooklyn-born soprano Marie van Zandt (1858-1919) “outshone her competitors with her extraordinary ability to learn parts quickly and to sing them perfectly.” Her mother was a well-known singer who traveled extensively across Europe, and she had professional connections with Paris and with the opera singer Adelina Patti. Marie made her stellar singing debut in Covent Garden in 1897, followed by resounding successes in Italy. At the age of 21, van Zandt signed a contract with the Opéra-Comique, and she soon eared her nickname “enfant gatée” (spoiled child). Predictably, she subsequently became the target of jealous colleagues and was “at the center of a series of near-riots in the city.” Marie led a life of successful artistic intrigue as she stole the heart of the Tsar’s cousin and subsequently married a Russian Count. Be that as it may, the French playwright and librettist Edmond Gondinet saw van Zandt in a performance of Thomas’ Mignon in 1880, and he was determined to find a suitable libretto for her.

Léo Delibes: Lakmé, “Flower Duet” (Anna Netrebko/Elīna Garanča)

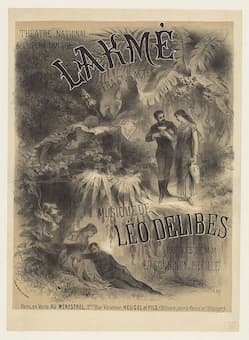

The poster of Delibes’ Lakmé premiere

His choice fell on a recent novel by Pierre Loti titled “Rarahu,” also known as “Le marriage de Loti.” Set in British India, Lakmé (soprano) is the daughter of Nilakantha (bass-baritone), a Brahmin priest who thirsts for revenge against the occupying British. A group of English people wander near Nilakantha’s home: two officers, Frédéric (baritone) and Gérald (tenor), Miss Ellen, Gérald’s fiancée (soprano), her cousin Rose (soprano) and their governess Mistress Bentson (mezzo-soprano). When the others move on, Gérald remains behind and is discovered by Lakmé as she returns to her house. Her mysterious beauty instantly entrances him, and the heroine is moved as well. But he has to flee at the approach of Nilakantha, who swears vengeance when he finds the unknown intruders have profaned his ground. We find the two officers in a market place, shortly before being posted to a distant province. Mingling with the crowd is Nilakantha who has asked his daughter Lakmé to sing to attract the intruder. She breaks off, fainting, when she sees Gérald in the crowd. Gérald rushes forward to support her: Nilakantha stabs him and flees.

Léo Delibes: Lakmé – Act I: Viens, Mallika (Mady Mesplé, soprano; Danielle Millet, mezzo-soprano; Paris Opéra-Comique Orchestra; Alain Lombard, cond.)

Léo Delibes: Lakmé – Act I: Miss Rose, Miss Ellen, respectez les clotures! (Paris Opéra-Comique Orchestra; Alain Lombard, cond.)

Lakmé – Production Opéra Comique 2017

Lakmé’s loyal servant Hadji (tenor) has sheltered the wounded Gérald in the forest, where Lakmé comes to tend him. While she is fetching water from the sacred spring that will seal their love, Frédéric comes to recall Gérald to his duty. Gérald agrees. Lakmé, returning, knows that he will desert her, so she snatches a poisonous datura leaf and swallows it. When Gérald realizes that she is dying for her love, he drinks from the sacred cup as a vow of fidelity as she dies, and Nilakantha is thwarted. Scholars have suggested that the “opera brings together many favorite features of the age: an exotic location, a fanatical priest figure, the mysterious pagan rituals of the Hindus and their bewitching flora, and the novelty of exotically colonial English people.” The plot, as in many other such novels, rests on the conflicts felt by both lovers as “both yield to the fatality of love.”

Léo Delibes: Lakmé – Act III: Sous le ciel tout étoilé (Joan Sutherland, soprano; Monte-Carlo National Opera Orchestra; Richard Bonynge, cond.)

Léo Delibes: Lakmé – Act III: Tu m’as donné le plus doux rave (Joan Sutherland, soprano; Alain Vanzo, tenor; Monte-Carlo National Opera Orchestra; Richard Bonynge, cond.)

Edmond Gondinet

Edmond Gondinet passed the novel to his friend Léo Delibes, who read it on a train journey to Vienna. Delibes immediately agreed and composed the score between July 1881 and June 1882. The premiere on 14 April 1883 at the Opéra-Comique (Salle Favart) in Paris was a resounding success, and Marie van Zandt was showered with accolades. It was the “conventional form and pleasant style with touches of exoticism, delicate orchestration and melodic richness, which earned Delibes a success with audiences.” The composer “treats the passionate elements in his story with warm and expressive music and reserves oriental color for scenes of incantation and ceremony, for prayers and dances and for the tumultuous market scene, often with modal scales. The music is always reserved and tasteful, deftly orchestrated and imbued with many subtle harmonic colors. The most celebrated numbers are the duet ‘Dôme épais’ for Lakmé and her servant.”

Léo Delibes

The opera remained in the repertory of the Opéra-Comique for some 80 years and was quickly produced on other stages as well. To be sure, the opera has given us some of the most celebrated numbers in the repertoire, including the “Flower Duet” from Act 1 and the “Bell Song” in Act 2, but in this time of everybody being offended on behalf of somebody else, it is now slandered for being “stuck in a racist, sexist past.” Lakmé alongside the entire genre of opera in the 19th century is a historical art form, a museum of musical and social conventions from the past. Making sure that the role of Lakmé is performed by a genetically and culturally verified Indian soprano and set on the planet “Righteousness” with the libretto cleansed of all offending words is not the answer; it takes historical contextualization, and detailed knowledge of musical, literary and theatrical styles and conventions.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Leo Delibes: Lakmé, “Bell Song” (Natalie Dessay)