By the death of Jules Massenet on 13 August, writes a correspondence for the Musical Times “France loses her most popular and most famous composer.” Contemporary critical assessment was rather less complimentary. “Massenet’s prolonged and widespread success,” according to Fuller Maitland, “is one of the puzzling phenomena of modern musical history. While those who look a little below the surface find his music inexpressibly monotonous, casual hearers are surprised by his superficial versatility… his chief idiosyncrasy as a man and an artist was an overwhelming desire to court success.”

Jules Massenet: “Meditation” from Thaïs

Mes souvenirs

Jules Massenet, 1895

When Massenet found out that the music editor of the Écho de Paris had asked Saint-Saëns to write his memoirs for the paper, Massenet immediately offered his Mes Souvenirs to the paper. The editor did not dare to refuse him, but on the other hand, had no desire to offend Saint-Saëns. To solve the dilemma, installments from the respective autobiographies were printed on alternate weekends, to the satisfaction of everybody involved. Massenet paints his life and career in the gentlest of colours, and even his enemies are lovable people whom he really adored. As a scholar writes, “the pathos of these memoirs comes not from the events they recount but from Massenet’s obvious desire for affection.”

While Saint-Saëns articles attracted lively interest among the intelligentsia, Massenet’s recollections drew large crowds hoping to find stories about their favourite actresses, backstage gossip, and revelation of the world behind the curtain. Readers quickly told Massenet that the book, however, was incomplete as it lacked a chapter about his death. Initially, Massenet laughed off this suggestion, but in his 70th year, he was beginning to be haunted by notions of death. As such, he added an appendix to his memoirs entitled “Pensées posthumes.”

Jules Massenet: Werther, “Pourquoi me réveiller”

Pensées posthumes

Monument of Jules Massenet

It is a rather bizarre passage where he sees himself leaving this world behind and living among the stars and brightly shining suns. As he writes, “I was never able to get such lighting for my scenery on the great stage at the Opéra where the backdrops were too often in darkness.” He bids farewell to the tedium of life and all the restless nights, the newspapers, and boring dinners. “An evening paper, or perhaps two, felt it to be its duty to inform its readers of my decease. A few friends—I still had some the day before—came and asked my concierge if the news were true, and he replied, ‘Alas, Monsieur went without leaving his address.’ And his reply was true for he did not know where that obliging carriage was taking me.”

“At lunch, acquaintances honoured me among themselves with their condolences, and during the day here and there in the theaters they spoke of the adventure: Now that he is dead, they’ll play him less, won’t they? Do you know he left still another work? He’ll never stop boring us! Ah, believe me, I loved him well! I have always had such great success in his work! A pretty woman’s voice is heard saying. As the carriage took me farther and farther away, the talking and the noises grew fainter and fainter, and I knew, for I had my vault built long ago, that the heavy stone once sealed would be a few hours later the portal of oblivion.”

Jules Massenet: Manon, (Excerpt)

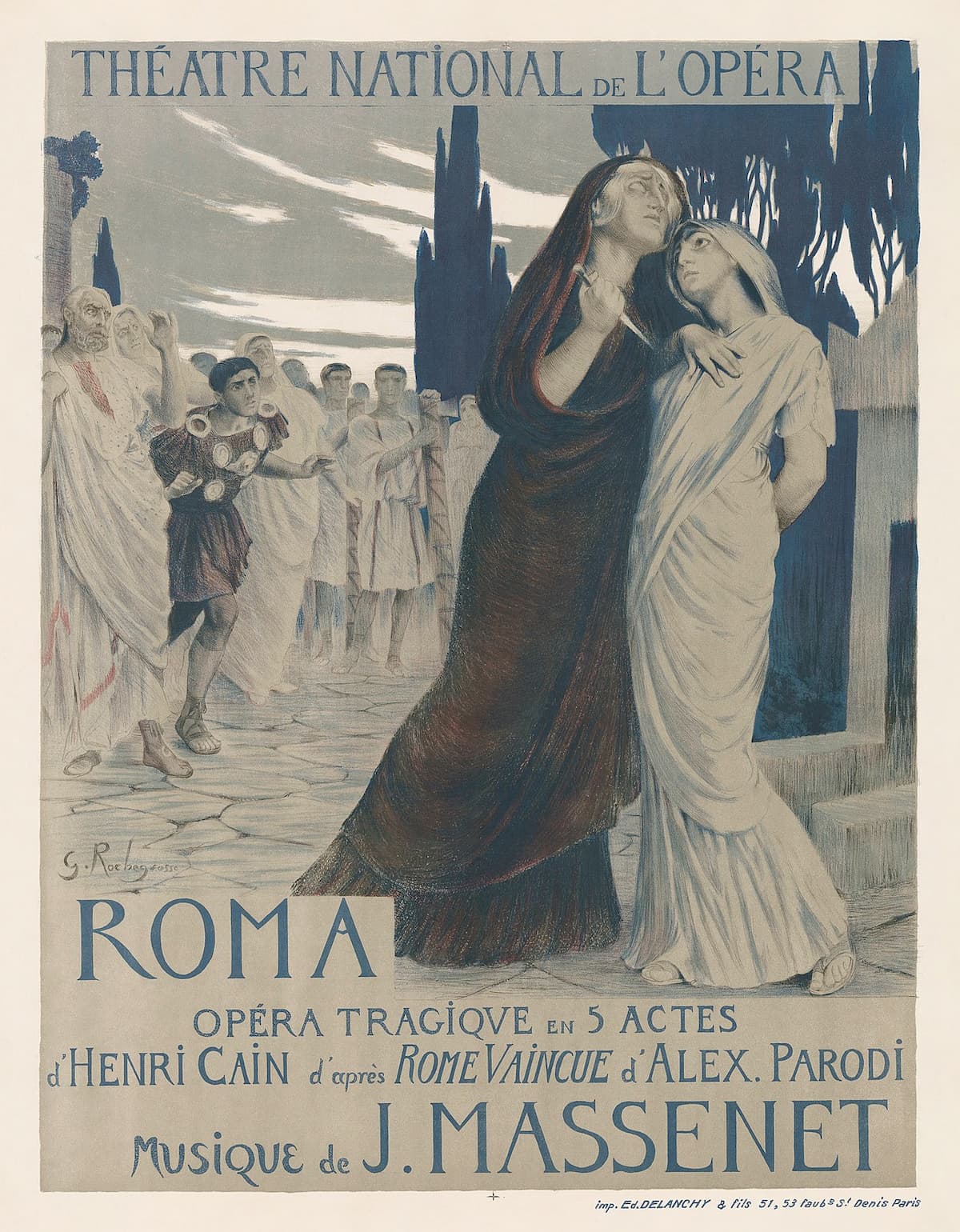

Roma

Jules Massenet’s opera Roma

The opera mentioned in “Pensées posthumes” turned out to be Roma, the last of his operas to premiere during his lifetime. Based on a play by Dominique-Alexandre Parodi, the story tells of a Vestal virgin who falls in love with an army officer and draws the wrath of god. She is sentenced to be walled up alive as a penalty, but moments before the sentence is carried out she is stabbed by her blind grandmother to spare her an agonising death. The work was first performed at the Opéra de Monte Carlo on 17 February 1912, and Massenet was in the audience. The audience was overjoyed, and Prince Albert spoke of the deep impression the new work had made upon him. However, approaching his 70th birthday he was very ill again and retired to his country house in Égreville.

Tomb of Jules Massenet

Massenet had been suffering from abdominal cancer for some months, and within a few days, his condition deteriorated sharply. On the evening of 12 August he arranged notes and music paper on his desk ready for the next day’s work, a ritual he had performed for over fifty years. Early in the morning of 13 August, at a time when normally he would have been at work, he lay restless and disturbed, and he died at 4am surrounded by his family. He was buried in the little cemetery at Égreville on 17 August. Only a small group of people had gathered, and the congregation included Reynaldo Hahn, Gustave Charpentier, and Raoul Gunsbourg. There was, by Massenet’s request, no music.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Jules Massenet: Roma (Iano Tamar, soprano; Svetlana Arginbaeva, contralto; Francesca Franzil, soprano; Angela Masi, soprano; Carmelita Mitchell, soprano; Warren Mok, tenor; Nicolas Rivenq, baritone; Jean Vendassi, baritone; Francesco Ellero d’Artegna, bass; Giacomo Rocchetti, baritone; Bratislava Chamber Choir; Orchestra Internazionale d’Italia; Marco Guidarini; cond.)