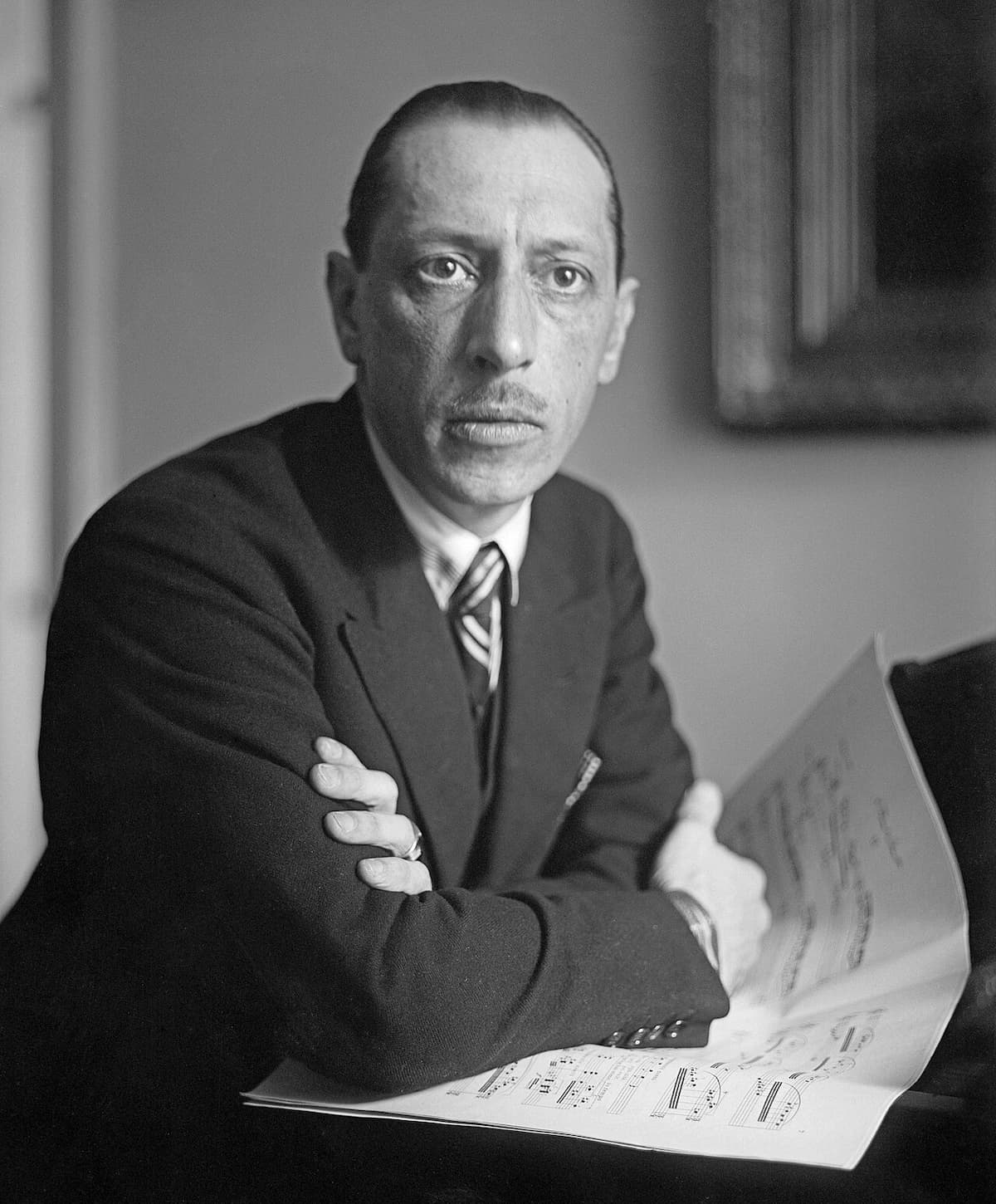

Igor Stravinsky visited the Chicago Art Institute on 2 May 1947. He was struck by a series of eighteenth-century paintings by William Hogarth titled “The Rake’s Progress.” This series of scenes from a drama suggested the subject for an English-language opera Stravinsky had wanted to write since arriving in the US eight years earlier. W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman were hired to fashion the libretto, and the work premiered at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice on 11 September 1951.

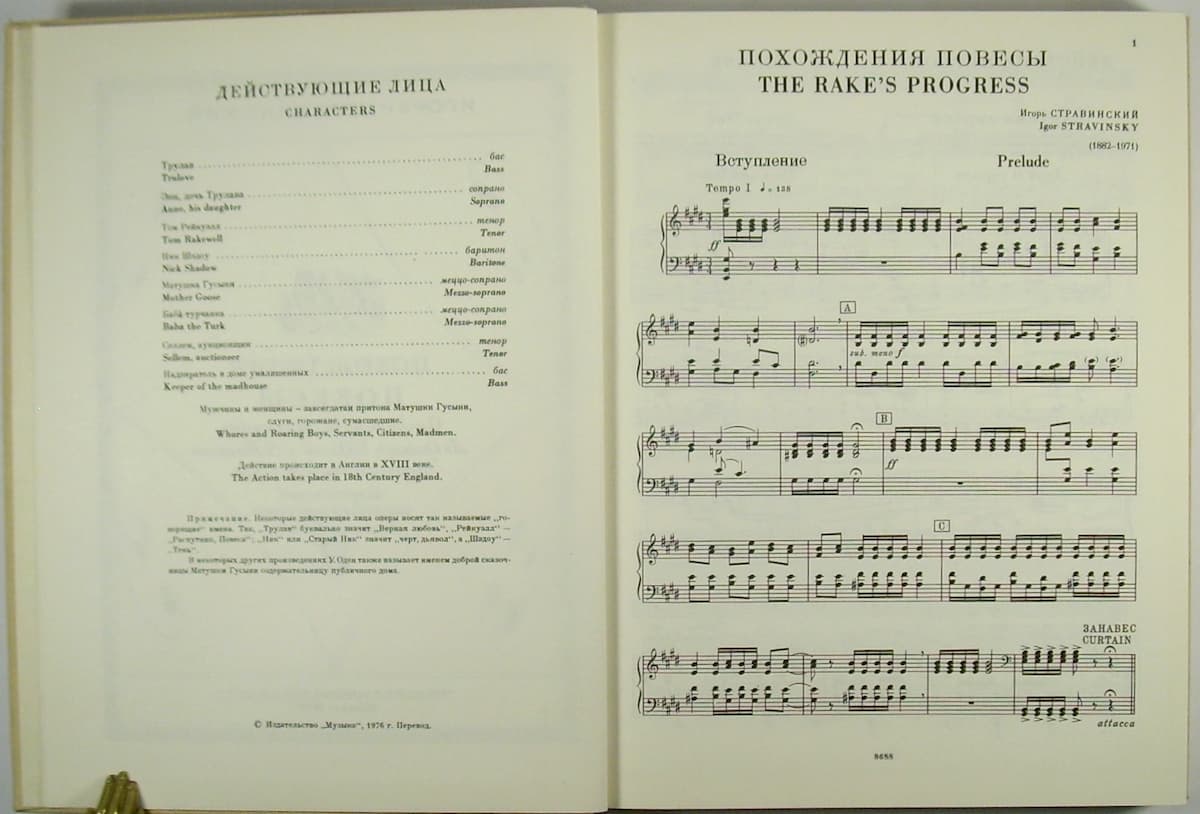

Igor Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress, “Prelude” (Colin Tilney, harpsichord; Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Igor Stravinsky, cond.)

The Story

Igor Stravinsky

Tom Rakewell and Anne Trulove celebrate the season and their love, while her father has doubts about the upcoming marriage. He proposes that Tom take a regular job, but Tom angrily reflects that he is not made for a life of drudgery but will trust fortune. He makes the first of the spoken wishes that provide the basic plot. When he wishes for money, Nick Shadow appears and tells him that an obscure uncle has died and left Tom a fortune.

Igor Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress, “Here I stand…”

Shadow invites Tom to employ him as a servant and accompany him to London to sort out the inheritance. Nick Shadow turns to the audience showing that he is not merely Tom’s alter ego, but truly the devil. The second scene is set in Mother Goose’s brothel, with Tom being introduced to the shady side of time. Tom is uneasy but accepts Mother Goose’s invitation to spend the night. Back in the country, Anne is uneasy as she has not heard from Tom and suspects he is in danger. She sets out for London to rescue him.

Igor Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress, “Come, master, observe the host of mankind.”

Act 2

William Hogarth: A Rake’s Progress – Tavern Scene

Tom is disillusioned with decadent urbanity and longs for the simple country joy he left behind. He pronounces his second wish, wanting to be happy. Shadow enters carrying an advertisement for Baba the Turk, the famous bearded lady, and suggests that he marry her. Anne, meanwhile has found Tom’s house in London only to see him emerge from a sedan chair which also contains Baba, whom he has just married. He tells Anne to leave but feels genuine regret.

Igor Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress, “Love Too Frequently Betrayed”

Tom finds marriage intolerable, as Baba has a fierce temper and won’t stop talking. Tom covers her head with his wig and falls asleep. Nick enters with a “fantastic Baroque Machine” that apparently turns stones into bread, and announces that if mass-produced, it could make Tom a saviour of mankind. Tom disposes of his wife and sets out to market the machine, not knowing that it is a sham.

Igor Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress, “No word from Tom”

Act 3 and Epilogue

Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress

The marketing plan has failed and ruined the Rake. The objects for sale at the auction include Baba, and she advises Anne to pursue Tom, who still loves her. She also warns her against Nick Shadow and announces her intent to return to the stage. In a graveyard, Nick finally reveals his identity and demands payment from Tom, in the form of his soul. They agree on a game of cards to determine Tom’s fate. Tom wins and Nick sinks into a grave, however, he condemns Tom to insanity as he departs.

Igor Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress, “As I was saying, both brothers wore moustaches”

We find Tom consigned to Bedlam, as he believes to be Adonis. Anne visits him and sings him to sleep, before quietly slipping away. When Tom realises she has gone, he dies. In the epilogue, each of the principal characters gives a moral drawn from their scenes in the opera, and together announce the final moral, “for idle hand, and hearts and minds, the Devil find a work to do.”

Igor Stravinsky: The Rake’s Progress, “I burn! I freeze!”

The Music

Igor Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, Glyndebourne

The Rake’s Progress is Stravinsky’s only full-length opera and one of his last neoclassical works. The opera borrows heavily from eighteenth-century tropes, making clear musical allusions to operatic traditions in both the libretto and the music. Stravinsky confessed that the late Mozart operas had been his sources of inspiration and style, even for specific figurations.

And he famously said to Nicola Nabokov, “I will lace each aria into a tight corset.” The Rake certainly has a complicated relationship with the past, and Stravinsky uses historical references in a variety of ways, including as pointed, and ironic commentary on the characters and situations.

Stravinsky later declared himself “Mozart’s continuer,” even though the musical structure is far less ambitious than Mozart’s. In fact, the opera relies to a great extent on the simple verse and refrain of the ballad opera. The premiere on 11 September was well received, and it was common to use the harpsichord for the opera, heightening the sense of past-ness. Richard Taruskin writes, today “the Rake has become a stout repertory item, with more productions than any other opera written after the death of Puccini.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter