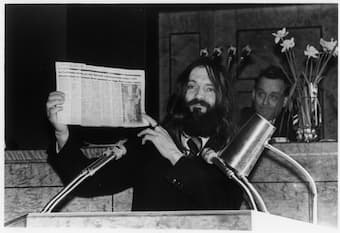

Arvo Pärt worked as a sound engineer at the Estonian Radio in the 1960s

© Vladimir Gorbunov/the National Archives of Estonia

Arvo Pärt was born on 11 September 1935 in Paide, in Järva County, Estonia, as the only child of Linda Anette and August Pärt. Raised by his mother and stepfather, the family moved to Rakvere, where he studied at Rakvere Music School (1945–53) and Rakvere Secondary School No.1 (1950–54). He quickly discovered his love for music and studied piano with Ille Martin. Pärt recalls, “as a little boy I sang around the house. We had a huge concert grand, but it was in such poor condition that we almost disposed of it. When I was seven or eight, I started taking piano lessons. It wasn’t very satisfying as the middle register of the grand was broken. So I played the notes of the low and high registers only. I combined reality with phantasy this way. When I grew up, I exchanged the hammers in order to tackle the middle register, but the action didn’t work as evenly as it should have because the hammers didn’t fit properly at every point. At that time I composed a lot for the piano.”

Arvo Pärt: Partita, Op. 2

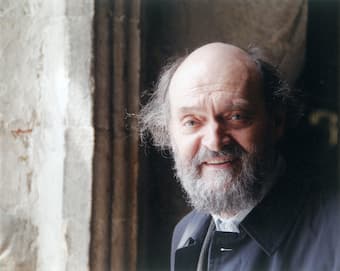

Arvo Pärt, 1979

His first serious study of music was interrupted by his compulsory military service in the Soviet army. He was released in 1956 from the army because of ill health and returned “to the Tallinn Music School where he studied briefly with Veljo Tormis.” Pärt eventually enrolled in the Tallinn Conservatory, studying with Heino Eller, and he graduated from that institution in 1963. A number of works composed during his student years still belong to the official list of his compositions, including the Partita for piano.

During his student days, Pärt found work as a recording engineer with Estonian radio, and he also composed modernist film and theatre music. Estonian music in the 1960s was shaped by “an entire generation of innovative composers with a modern approach, including Eino Tamberg, Veljo Tormis, Jaan Rääts and their junior follower Kuldar Sink.” All the most important styles and compositional techniques of the 20th century were introduced to Estonian music, and Pärt became a pioneer in many of these areas. In fact, he became one of the leading figures in the Soviet avant-garde. Yet almost from the get go, Pärt’s search for a distinct musical identity brought him into direct conflict with Soviet authorities.

Arvo Pärt: Symphony No. 1, “Polyphonic” (Bamberg Symphony Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

© Kaupo Kikkas

The composer remembers, “In the course of my life there have been several upsets. It started as far back as 1961, when I composed Nekrolog, which was my first large orchestral piece. I was a student at the conservatory of music in Tallinn, and I had written the piece in 12-tone-technique, which was at that time and place extraordinary. As a result there was strong criticism from the highest circles. Nothing was considered more hostile than so-called influences from the West, to which 12-tone-music belonged.” Tikhon Khrennikov, the leader of the Union of Soviet Composers, officially renounced the “exclusive small group of composers existing in the backwater of the broad stream of musical life and engaged in formal searching and fruitless experimentation…This composition makes it quite clear that the twelve-tone experiment is untenable: ultra-expressionistic, purely naturalistic depiction of the state of fear, terror, despair and dejection.” Pärt also introduced collage-technique in 1964, but as a scholar writes, “none of those styles remained permanently in his work nor interested him for very long. Instead, many of his early compositions can be viewed rather as brilliant experiments or testing the boundaries.”

Arvo Pärt: Sonatina, Op. 1, No. 2

© Eric Marinitsch

Pärt kept ignoring the official reprimand and threats, as “it was not his musical language that provoked an official scandal, but the avowal of Christianity in his Credo. That work was basically banned, and Pärt as well as his music fell into disfavor for several years. Eventually forced to emigrate, Pärt equates “composition with breathing in and out. It’s my life. What does a child do when he plays on his own? He sings. Why does he sing? Well, he is happy about something pretty, he is inspired by something. That is something healthy, quite natural. For adults this state is considerably more complex, for this harmony is smashed into pieces, it’s lost. But can I exist without composing, my soul and my spirit? Music is already my language. My music can be my inner secret, even my confession. But what is my confession? I don’t confess in the concert hall, in front of an audience. It is directed toward higher instances. The necessity for composing has many layers. They are like bridges, put on top of each other. And you never know which one you are just passing. Some are dangerous and you fall. Most important for me: that I cannot say in a thousand sentences what I can say in a few notes.” Asked about art and responsibility, the composer wrote, “The social responsibility of a person consists in being responsible before God and before your own soul. If both of these were in order, then responsibility before society would function automatically. But if you begin with the social aspect, then you can never know where it may all lead and how the good intentions may end.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Arvo Pärt: Collage über Bach

Arvo Part was born an Estonian, and in spite of the Soviet Union’s illegal occupation of Estonia, Mr. Part remained Estonian. He may have been part of the Estonian “avant garde” but he should not be described as being part of the Soviet Union cultural scene.

This composer has my highest admiration for staying true to himself and focusing on creation of his music as a gift by and to his Creator. Love the Spirituality within his compositions.