All beginnings are difficult, but you have to start somewhere. This might well have been the motto for Guntram, the first opera by Richard Strauss. Or, as the composer himself declared, “all of Guntram is a prelude.” Working on the libretto since 1888, Strauss composed a substantial part of the opera during his holiday stay in Egypt in 1892/93. The premiere on 10 May 1894 at the Hoftheater in Weimar was reasonably successful, but neither audiences nor critics found the work particularly inspiring.

Richard Strauss: Guntram, “Part 1”

The Story

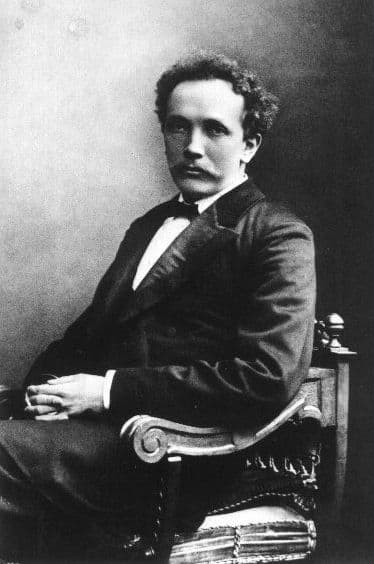

Richard Strauss

Set in medieval Germany, the story details a triangular Wagnerian narrative of love and redemption. Freihild is the unhappy wife of the tyrant Duke Robert (baritone), who obstructs all her charitable projects. The knightly minstrel Guntram (tenor) is a member of a high-minded, pacifist Christian brotherhood. He arrives just in time to prevent Freihild from drowning herself. As Guntram is invited to the court, he rules the ire of the duke by singing a eulogy to peace and generous rulers and urges a rebellion.

Robert attacks Guntram, and the duke is promptly killed. While sitting in prison, Guntram reflects on his true motives. Friedhold (bass), an elder of the brotherhood, declares that Guntram has committed an absolute sin, but the knightly minstrel insists that only his own choice can make atonement. Things get interesting when Freihild arrives, as Guntram realises that his violent act was inspired not by ideals of liberation but by his love for her. He renounces the brotherhood and his adored lady and departs for solitude as a hermit, while Freihild rules benevolently over her peasants.

Richard Strauss: Guntram, “Act I Scene 2, “Freihild! Was hör ich?” (Reiner Goldberg, tenor; Sandor Solyom-Nagy, baritone; Hungarian State Orchestra; Eve Queler, cond.)

The Aftermath

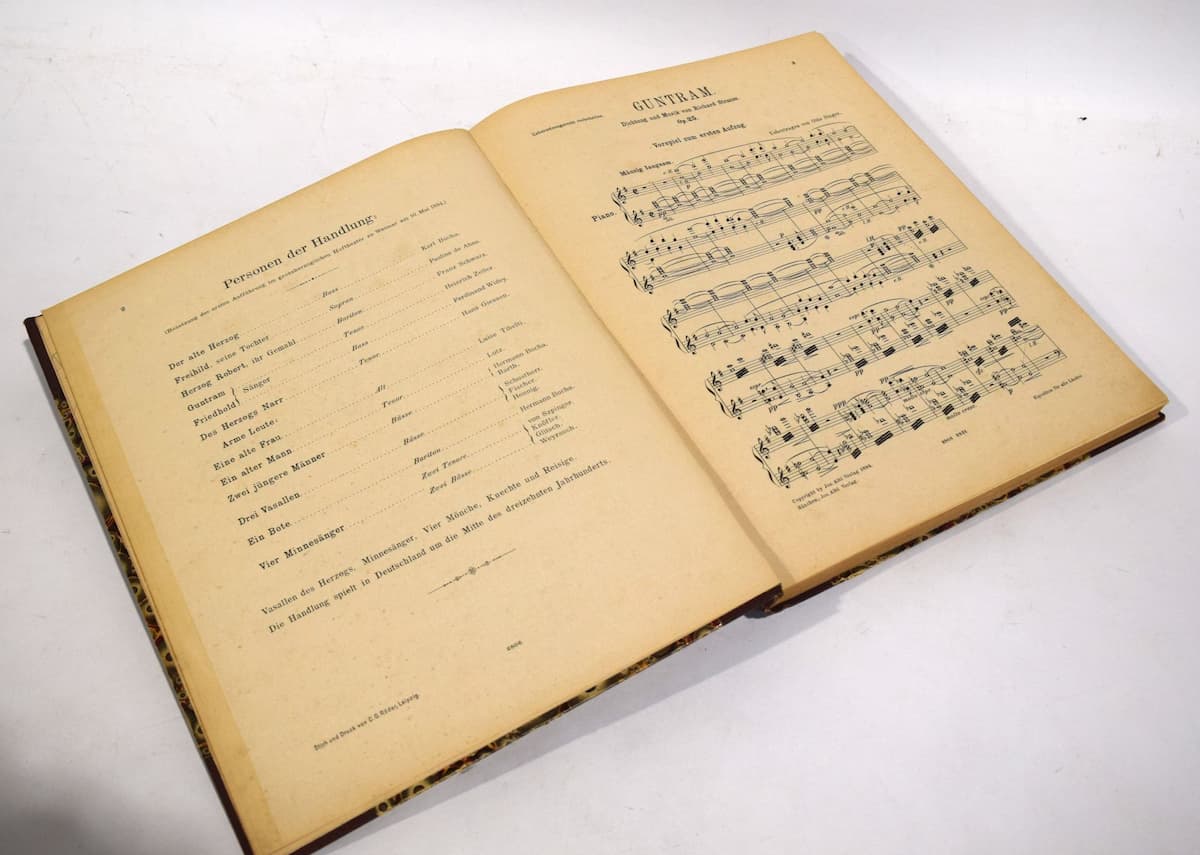

Richard Strauss’ Guntram score

At the time of the Guntram premiere, Strauss had already achieved popular success with his tone poems Don Juan and Death and Transfiguration. However, when Strauss brought Guntram to Munich for a single performance on 16 November 1895, the reception was devastating. Two of the principals refused to sing it, and the orchestra asked the director to spare them “this scourge of God.” The story was considered “naïve, clichéd, and lacking any theatrical excitement or spectacle.”

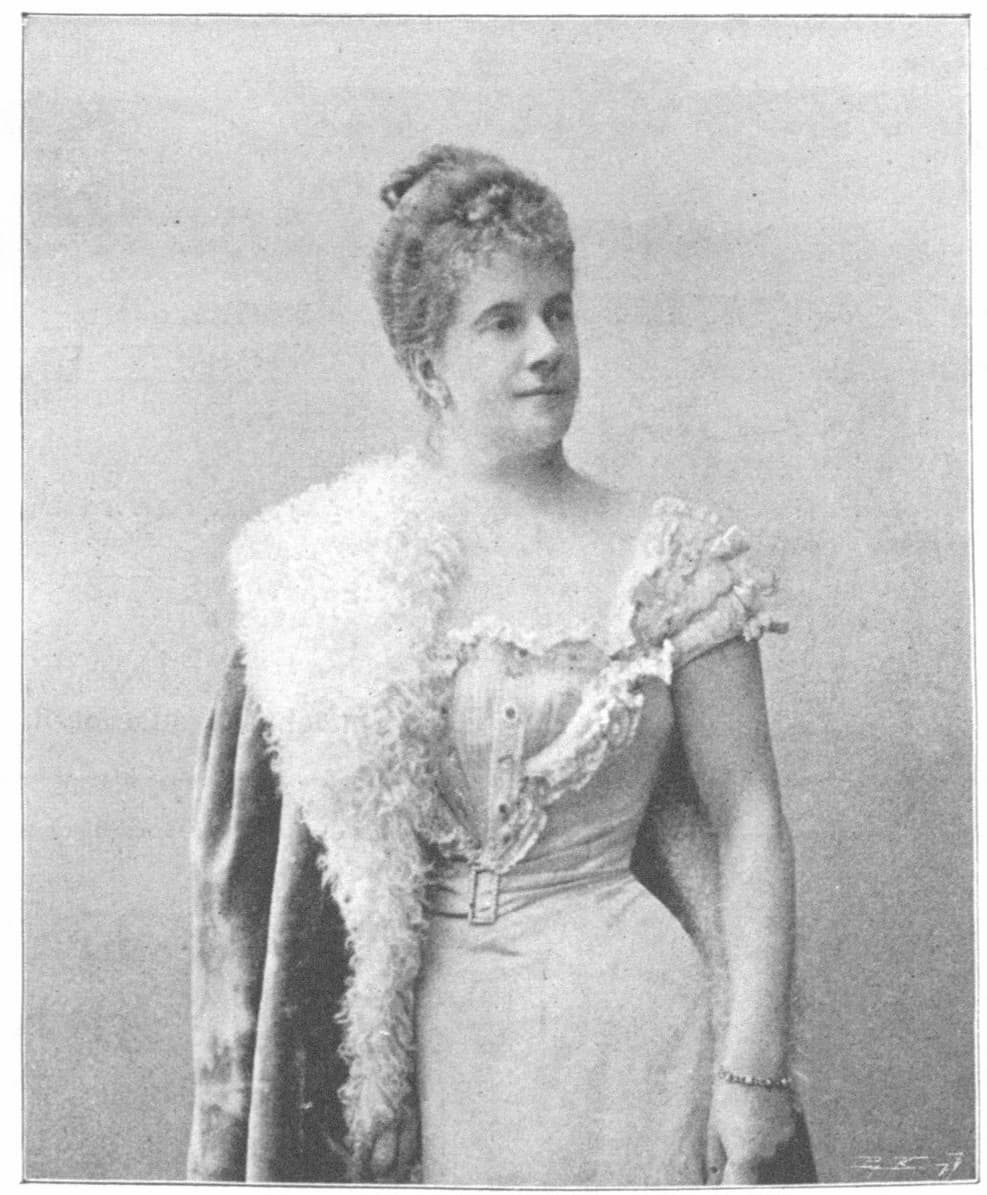

Strauss had written an inscription on the short score that reads, “Thanks to God and to the sacred Wagner.” No wonder that it was considered a work that “Strauss had written while suffering from a very severe attack of Wagnerian flu with mystical complications.” Critics did praise the “undoubted nobility and purity” of Strauss’ artistic intention and his orchestral genius. And the soprano role of Freihild at the premiere was sung by Pauline de Ahna on the day that Strauss announced their engagement.

Richard Strauss: Guntram, Act II Scene 2 “So verfalle das Reich in Schutt und Staub” (Sandor Solyom-Nagy, baritone; Hungarian State Orchestra; Eve Queler, cond.)

The Music

Pauline de Ahna

Strauss symbolically erected a gravestone to the memory of Guntram, his so-called “child of sorrow.” The epitaph reads, “Here rests the honourable and virtuous young man Guntram… who was horribly slain by the symphony orchestra of his own father.” The Wagnerian influence is undisputed, as can be gauged by a lovely anecdote from the rehearsal for the premiere. Apparently, when Strauss stopped rehearsal and reproved the orchestra for playing a passage inaccurately, a cellist responded, “But Maestro, we never get this passage right in Tristan either.”

Regardless of the obvious Wagnerian influence, the music does show a composer who is strikingly moving towards his own melodic and harmonic direction. It does contain well-crafted music, particularly in the “Overture,” as it presents the major themes of spiritual love, the brotherhood, and Guntram. Critics call the score “lugubrious and unmemorable, full of grand, sweeping, rhetorical gestures that go nowhere.” And while the music is described as “a lot of pomposity, hothouse emotion, and self-indulgent histrionics,” the fingerprints of Richard Strauss are all over the score.

Richard Strauss: Guntram, Act III Scene 2 “Guntram! Guntram, was ist dir?” (Ilona Tokody, soprano; Hungarian State Orchestra; Eve Queler, cond.)

The Revival

Scene from Guntram

Strauss took seven years to attempt another opera, but he still considered Guntram a worthy effort. On his 70th birthday, a German radio station honoured the composer by broadcasting a concert version of Guntram. At that time Strauss sarcastically remarked, “Guntram contained so much beautiful music that it well deserved a revival, if only because of its historic interest as the first work of a musical dramatist who was later to become successful.”

Strauss did revise the score in 1940 by making substantial cuts, and you are most likely to hear this version if you’re lucky enough to catch Guntram on stage today. For many observers, the revision “remains undramatic and static.” However, you can still hear some lavish quotations from Guntram in Strauss’ tone poem Ein Heldenleben, where Guntram is referenced in the section titled “The Hero’s Works of Peace.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter