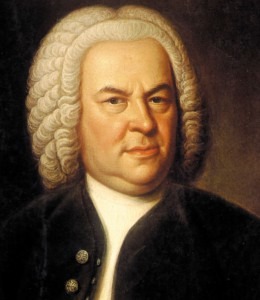

Bach

Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248

The earliest Christmas hymns, dating from around the 4th Century, were essentially statements of theological doctrine. Popular Christmas songs in respective native languages — something resembling the traditional Christmas carols — emerged in the 13th and 14th Centuries. Completely secular Christmas songs were invented in the late 18th Century. Take for example the Christmas classic “Jingle Bells.” It was copyrighted in 1855 with original lyrics not connected to Christmas at all. Rather, the words tell the story of the seduction of Miss Fannie Bright during a sleigh ride. As such, it is hardly surprising that contemporary Christmas performances limit their presentation to the first two stanzas of the text! However, various composers have also set the central story, which after all is the birth of Jesus Christ, to music. Notably among them is the Historia der Geburt Jesu Christi (Story of the birth of Jesus Christ) composed by Heinrich Schütz. Rightfully considered one of the foremost composers of the 17th Century, Schütz published his Oratorio — a non-staged concert piece combining sacred dialogues and narrative mediations with music that includes choral declamations, instrumental dances and monodic signing — in 1664. Besides prominently featuring an Evangelist and all the principal characters of the Christmas story, the work also calls for two choirs, consisting of four and six voices, respectively. This polychoral feature was clearly the result of his study with Claudio Monteverdi in Venice. In many respects, this late work by a great master has many pioneering features. Foremost among them is a free recitative style of the narration by the Evangelist. Schütz wrote, the words should be sung “in a clear narrative style by a tenor with a good light voice, who is able to match the music to the natural rhythm of the words.” The influence of this works on subsequent generations of composers, particularly on Johann Sebastian Bach, cannot be emphasized enough. In 1734, Bach was cantor for the churches of St. Thomas and St. Nicholas in Leipzig and responsible for the music during Services at both locations. That year he composed the six musically and textually interrelated cantatas to which he appended the title Weihnachts Oratorium (Christmas Oratorio). Destined for the twelve days of Christmas, beginning on December 25th and ending on the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6th, Bach collaborated on the libretto with Christian Friedrich Picander, who had already provided him with many earlier librettos, including the one for the St. Mathew Passion. The biblical narrative is assigned to the tenor evangelist who declaims the text in recitative. Representing the congregation’s response of prayer, praise and thanksgiving for the Christmas message, a choir intones Lutheran hymns in Bach’s harmonization, while extended and elaborate arias provide the opportunity for further reflection. Bach had originally composed the music for these arias at an earlier time, using them for secular purposes. He now artfully fitted these pre-existing melodies with new text to suit the sacred context. Although we commonly think of this Oratorio as a single six-part unit, in reality it is a cantata cycle that unfolds over a thirteen-day period. That is, the whole work should never be performed in one single concert, and Bach certainly never did. Part 1, telling the story of Christ’s birth is intended for performance on the “First Day of Christmas,” December 25. “The Second Day of Christmas,” December 26, features the cantata regarding the annunciation to the Shepherds, and Part 3, celebrating the adoration of the Shepherds is heard on the “Third Day of Christmas,” December 27. The feast of the Circumcision and naming of Jesus is musically presented on January 1, while the “First Sunday of the New Year,” features the journey of the Magi. The concluding cantata is destined for the “Feast of the Epiphany,” January 6, and tells of the adoration of the Magi and the Flight into Egypt. In 1734, Bach was at the height of his compositional powers, and he created a wondrously dramatic and celebratory work. If you are tired of being trampled by shoppers, desperately trying to find some peace and quiet or simply want to hear some wonderful music this Christmas season, you might want to give Bach’s Christmas Oratorio a try. Merry Christmas!