The world of music is numerously populated by compositions that openly celebrate courtship, love, sex, and marriage. Equally numerous, although less overtly advertised, are works that exult in the suspension of a partnership, the break-up of a relationship, or the decree of final divorce. And one such work is the Elegie by the Swiss composer and conductor Othmar Schoeck (1886-1957).

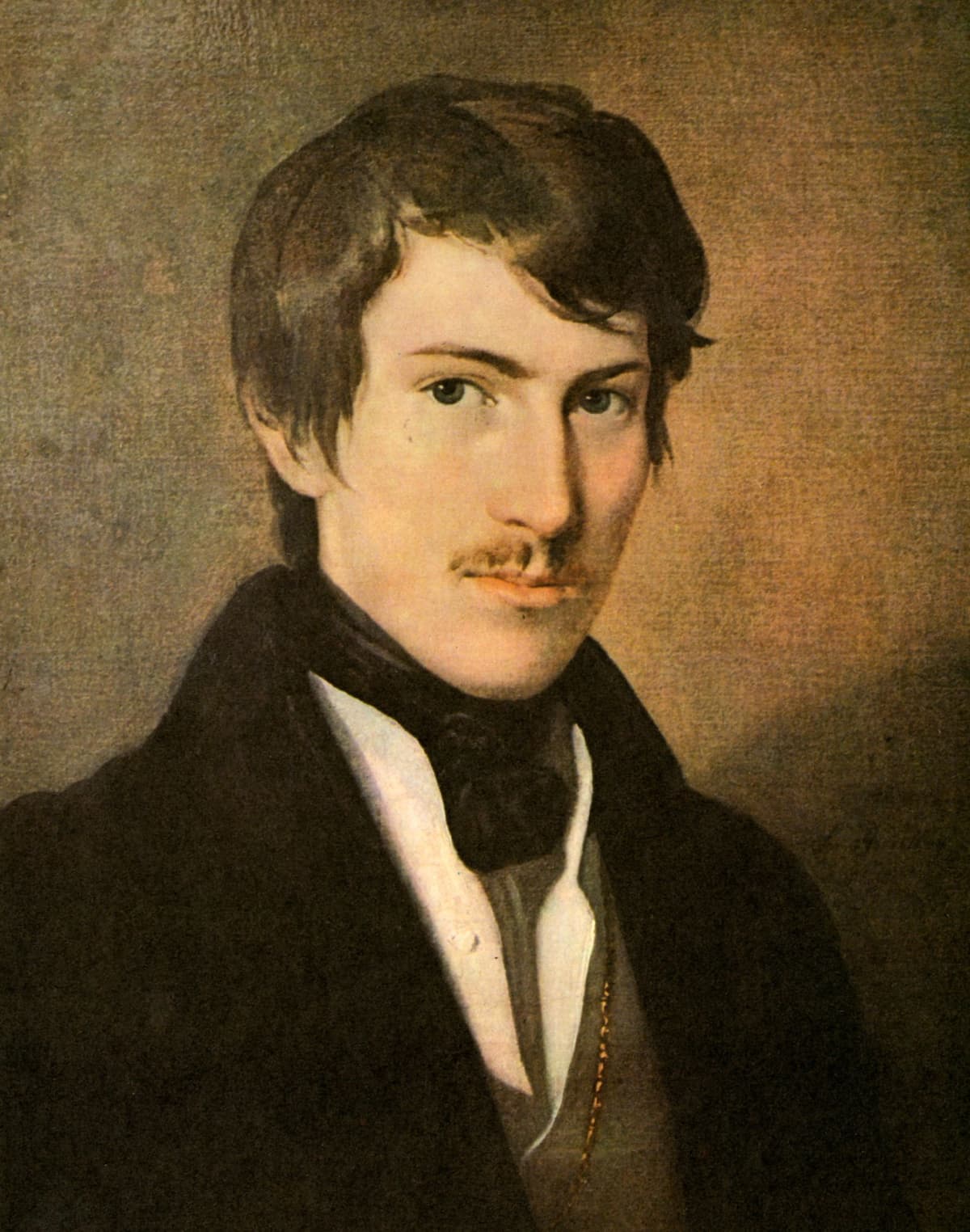

Othmar Schoeck

It all started when the Genevan pianist Mary de Senger auditioned for some concerto engagements in 1918. She later recalled their first meeting: “I first met him on 12 August 1918 in the small first-floor flat that he rented on the Zeltweg, of which the windows open out onto the garden.” She played Bach’s Italian Concerto for Schoeck, and he considered her performance “quite perfect.” They then played piano duets, and after exchanging some pleasantries headed straight for the bedroom. As Schoeck proudly told his friend Hans Corrodi, “by ten o’clock in the evening, his new-found love had already been consummated.”

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 1. Wehmut (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 3. Stille Sicherheit (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 6. Zweifelnder Wunsch (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

While the relationship had gotten off to a rousing start, it soon became complicated. The lovers spent three glorious days in the Hotel Bristol in Lausanne, but then Schoeck simply didn’t contact Mary for several months. She was none too happy, and after a particularly virulent quarrel in September 1919, it was Mary who failed to contact him for several weeks. Consumed by doubt and jealousy Schoeck suggested, “Now I have to do penance for my former sins.” Paralyzed and unable to think about anything but Mary, he stopped working on his opera and was only capable of writing a small piano piece. The affair did eventually resume its course, but it was strained by countless quarrels, periods of extended separations, and tearful reconciliations. After a particularly challenging relationship crisis in 1921, with Mary deciding to break off all contact for several months, Schoeck set two poems by Joseph von Eichendorff, “Nachklang,” and “Vesper.” Stimulated by his fear of losing Mary de Senger, Schoeck eventually composed a series of songs that grew into an extended song cycle.

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 8. Waldgang (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 11. Vesper (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 12. Herbstklage (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Joseph von Eichendorff

The lovers eventually reconciled, and Schoeck declared in 1922 that he wanted to marry Mary. The proposal was accepted, and he took Mary to meet his parents. However, he never made any mention of the engagement nor of impending marriage plans during that visit, and the affairs dragged on unhappily. Schoeck continued to compose individual songs, which he sent to Mary with love messages scribbled along the margins. In August 1922 Schoeck grouped the songs to form a cycle, and he arranged it for ensemble. He explained the reason for the instrumental arrangement by stating, “the song that the instrumental arrangement, ‘accompaniments’ were on the whole very simple and demanded more sustaining power than was capable on a piano, where held notes would die away too quickly.” Ultimately, according to the composer, the Elegie Op. 36 portrays “the narrative of a dying love,” with the actual relationship barely lasting beyond its first performance.

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 14. Nachklang (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 15. Herbstgefühl 2 (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 18. Waldlied 2 (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Nikolaus Lenau

Mary de Senger left Othmar Schoeck for good in August 1923. Essentially, Schoeck musically encoded 24 poems by Nikolaus Lenau and Joseph von Eichendorff, expressing his anxiety of uncertainty. From the very beginning, we are transported into a hypnotic world of nostalgia and sadness. Beautifully drawn vocal lines carry the psychological drama of individual poems and gently nudge the cycle’s dramatic trajectory. Transparently orchestrated, these poetic miniatures create a powerful and concentrated atmosphere without ever imparting a sense of desperation or violence. As a gesture of final farewell, Schoeck lavishly dressed his song cycle in the rich and largely conservative harmonic language of the late Romantic period. In essence, the Elegie is not merely a farewell to lost love, “but an elegy to the tonal musical language of the late 19th century, a musical language to which Schoeck had adhered longer than many of his contemporaries.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 19. Herbstentschluss (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 22. Welke Rose (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Othmar Schoeck: Élégie, Op. 36 – No. 24. Der Einsame (Andreas Schmidt, baritone; Winterthur Musikkollegium; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)