Samuel Adler: Pasiphae

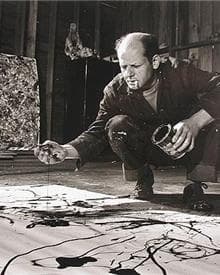

Jackson Pollock (photo by Martha Holmes)

In the mid-1940s, Jackson Pollock started on a series of mythologically themed pictures, the largest of which was Pasiphae. Pasiphaë was the daughter of the god of the sun, Helios, and Perse, an Oceanid nymph. She was married to King Minos of Crete but fell in love with a white bull that had been sent by Poseidon – Minos was supposed to sacrifice the bull, but substituted another in its stead and in revenge, Poseidon made Pasiphae fall in love with the bull. Their child was the Minotaur, who had the head of a bull and the body of a man. In his unnatural state, the only nourishment the Minotaur took was to eat humans. He was eventually killed by Theseus.

In Pollock’s painting, a central figure is watched by two sentinel-like standing figures at the left and right. Surrounding the figures are all kinds of arcana – symbols and free-form abstractions that seem to be taken from the Surrealist process of automatism, where the artist’s hand is driven by his unconscious in organizing the painting.

Pollock: Pasiphaë (1943) (Met Museum)

Pollock’s process for the work started with lightly painting the 3 figures and, applying colour in thin washes to build up to more opaque layers. The three figures are the compositional backbone of the work. ‘Dramatic linear accents were then introduced – at first around the contours of the coloured patches, and then cutting across these shapes to establish independent rhythms. To control this momentum and to re-establish order, Pollock next overpainted parts of the painting – particularly conspicuous is the grey overpainting at the top of the canvas. He applied each layer of paint directly and with increasing vigour, using not only brush, but palette knife and paint squeezed straight from the tube, to animate and extend the power of his drama.’

In a field of swirls, angular lines, and broken forms, given without any indication of depth, we have the start of what would late come to full fruition in Pollock’s more famous drip canvases.

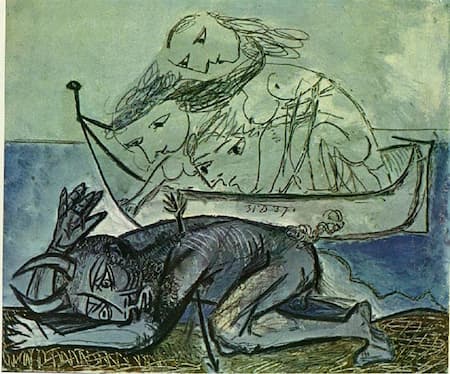

The figure in the middle of the canvas is not, as we might supposed, Pasiphaë, but rather the Minotaur. Pollock’s original title for the painting was Moby Dick and later, without any changes made to the picture, Pollock changed the title to that of the Greek queen after hearing her story told to him by a curator at the Museum of Modern Art. The minotaur was a favourite character of the surrealists and he figures largely in Picasso’s works.

Picasso: The Minotaur is wounded (1937)

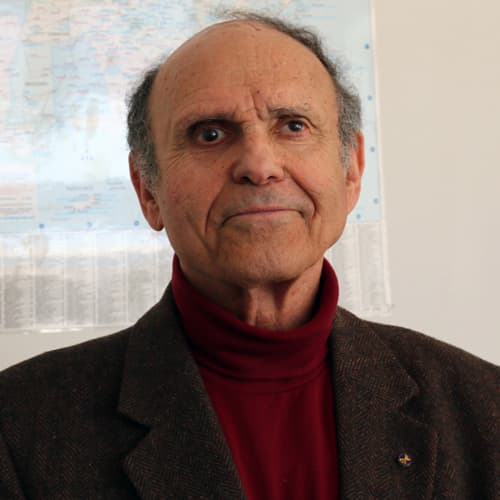

Samuel Adler (b. 1928) had seen Pasiphaë at the Met Museum in New York when he was asked by the piano and percussion duo of James Avery and Steven Schick for a work. He thought about the Pollock painting as the starting place for the work. Although Pollock’s work is one of wildness and complexity, Adler’s work starts with a peaceful mood of entry to the museum. Once in the museum, the viewer becomes overwhelmed by the works that surround him. Adler seeks to represent all the viewer’s internal emotions when looking at what he considers ‘an incredibly exciting abstract painting.’

Samuel Adler: Pasiphae (Roger Schupp, percussion; Laura Melton, piano)

Samuel Adler

In titling his work with a name of someone who’s not actually in the picture, but of something that was the fruit of her work, Pollock is telling us at the same time that this title isn’t descriptive but indicative. He’s asking the viewer to look beyond the surface of the three figures. He takes one of the great symbols of surrealism, the minotaur, and looks back into its history. As much as the minotaur stood for the surrealists for the ‘conflicting aspects of the human psyche,’ Pollock asks us to look at where that conflict might have come from.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

I love the Adler piece. Reminds me of Sam Adler’s “system” for writing 12 tone music that preserves many of the things we like in tonal music (like pitch repetitions).

If possible, pass my comment on to him. He was my teacher more than 50 years ago. It’s always good to see what he is doing.