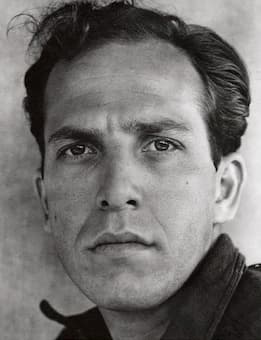

Philip Guston

The art of Philip Guston (1913-1980) remains controversial even 30 years after his death. A founder of the New York School, this abstract-expressionist was not afraid of putting his beliefs on canvas.

One of his early 20th century works, The Struggle Against Terror, a fresco painted in museum in Morelia, Mexico, with Reuben Kadish and Jules Langser, that took aim at antifascism and the Catholic church, comparing the torture and pain of modern-day (1934-5) terror victims with the tortures of the Spanish Inquisition. The 40-foot mural was hidden behind a wall for nearly 40 years until it was uncovered again in the 1980s. A 2020 exhibition of his work that contains his paintings of figures in Klu Klux Klansman garb has been delayed until 2024 because of the current Black Lives Matter movement, despite the fact that Guston said that the images were self-portraits from his imagination.

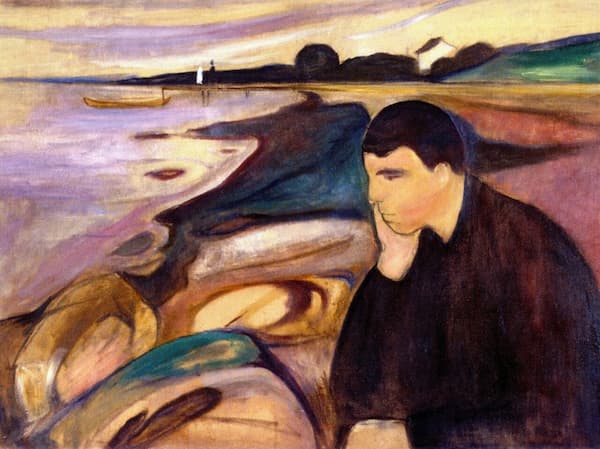

Guston: Painting (1954) (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

One of the paintings in his abstract-expressionist style was simple entitled Painting. Done in 1954, it looks initially like a crimson fog coming out of a bluish-greenish background. When looked at in close-up, however, Guston’s delicate paint strokes come out – meticulously controlled and precisely angled. On one side, a more definite green emerges; in other places, the red dominates.

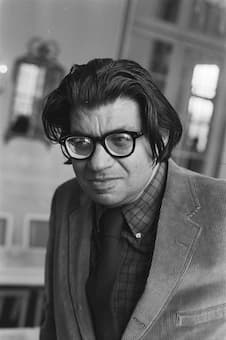

When we compare this work with a musical work, we can look at Morton Feldman’s 1984 work For Philip Guston. Written 4 years after Guston’s death, the work pulls at many of the same lines that Guston was attempting. Written for 3 instruments (flute, piano/celesta, percussion), Feldman’s work makes music out of both sound and silence, much as Guston’s work makes a painting out of many small elements. Feldman begins as he means to go on: four notes and silence.

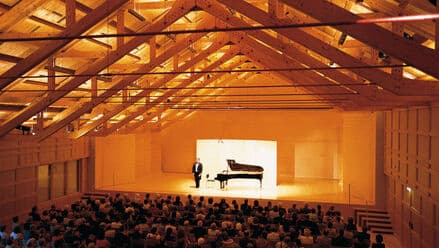

Morton Feldman: For Philip Guston: – (Eberhard Blum, flutes; Nils Vigeland, keyboards; Jan Williams, percussion)

Morton Feldman (1976)

Just as Guston’s work initially seems like a coloured fog, Feldman’s work seems to be equally insubstantial. Initially, the three instrumentalists seem isolated, brought together for this four-hour piece for seemingly separate reasons. When you look at the score, however, something else emerges. Everything you’ve heard has been precisely laid out. As one writer noted:

Take, for example, the final 15 bars of the work; on paper they run Like this: 7/4, 6/4, 5/4, 9/8, 11/8, 13/8, a silent measure of 2/2, 5/4, 5/4, 6/4, another silent measure of 2/2, 13/8, 9/&, 1 1 /&, a final silent 2/2. Four hours and some minutes have gone by…

Morton Feldman: For Philip Guston: – (Eberhard Blum, flutes; Nils Vigeland, keyboards; Jan Williams, percussion)

Feldman saw the piece as a conversation. “I see it,” said Feldman in a pre-concert talk at the premiere of the work at CalArts, “as a talk by two people, telling their story continuously with notes or with images, in a style fluctuating from one to the other. This is only possible in a long work.”

One audience member who heard the work in the 1990s said that, by the end, four hours later, the audience of 30 had reduced to 10 members, and the 10 who remained hadn’t moved a muscle, they thought, the entire time. Silence and sound: from the first 4 notes and its following silence, Feldman takes us to his own abstract-expressionist world.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter