Jake Heggie: Statuesque

American composer Jake Heggie (b. 1961) started the piano when he was seven and composing when he was 12. A commission from the San Francisco Opera led to the start of his successful opera career when he composed Dead Man Walking, working with librettist Terence McNally in 2000. Another side of his vocal writing is his songs and we’ll look at his Statuesque song cycle here.

Originally written for voice and 7 instruments (flute, clarinet, alto sax, violin, cello, bass, and piano), the work received its premiere in 2005 with mezzo-soprano Joyce Castle.

Using as its focus five iconic sculptures of women, Statuesque moves us through time from the modern Henry Moore back to the Egypt of Queen Hatshepsut. The songs are set to texts by Gene Scheer, which set each woman in her own world. Each woman speaks for herself.

The first sculpture is Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure in Elmwood, dating from 1939. Both a reclining figure and an earth figure with hills and dales, the sculpture is one of Moore’s rare pieces in wood. In Gene Scheer’s text, the statue says: ‘I am filled with unexpected shadows’

Henry Moore: Reclining Figure in Elmwood, 1939 (Detroit Institute of Arts)

Jake Heggie: Statuesque – No. 1. Henry Moore: Reclining Figure in Elmwood (Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; Jake Heggie, piano)

Next is a statue by Picasso of Marie-Thérèse Walter from 1932, done in his studio outside Paris in Boisgeloup. He sculpted her head in a classical mode, but always in the style of Picasso. In the text for this, we have a dialogue between Picasso and Marie-Thérèse, which takes them from their initial meeting through their breakup, ending with the intriguing ‘ “Can you keep a secret?” “No.”’.

Pablo Picasso: Head of a Woman, 1932 (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

Jake Heggie: Statuesque – No. 2. Pablo Picasso: Head of a Woman, 1932 (Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; Jake Heggie, piano)

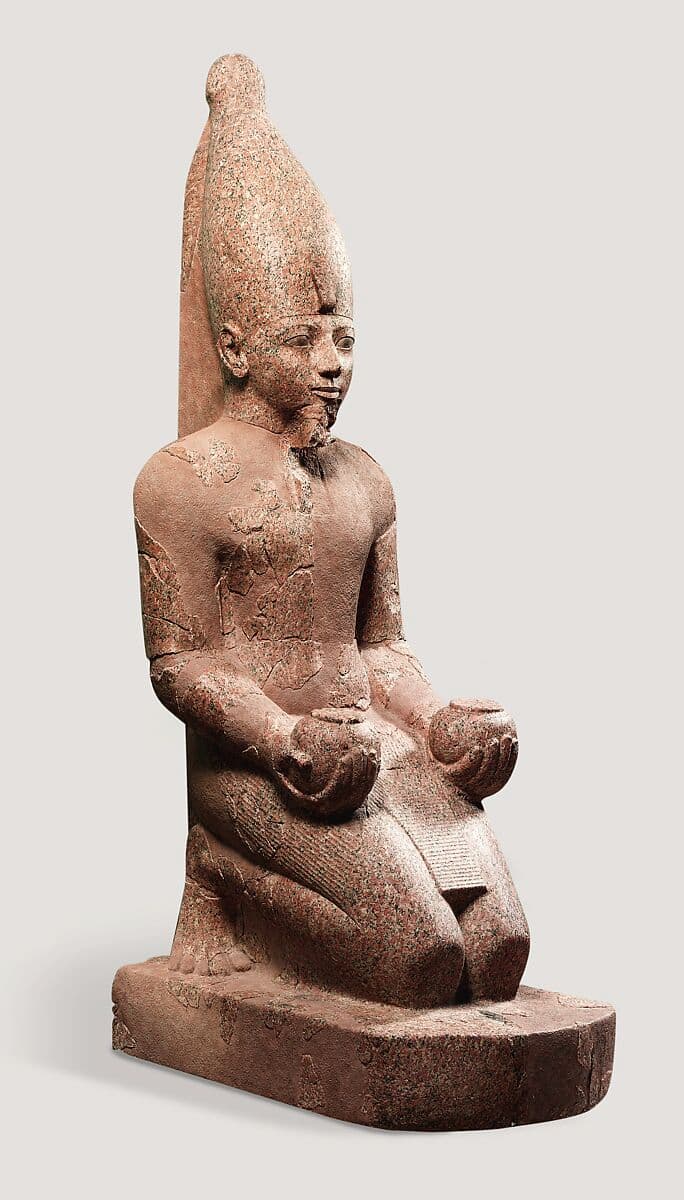

Now we turn back in time to the 1470s BCE. Queen Hatshepsut was ‘the first great woman in history’ about which we know something. Married to her non-royal half-brother Thutmose II at age 14, the royal Hatshepsut was the real power behind the Egyptian throne, both in making her husband royal and in ruling with her stepson/nephew, Thutmose III. When she declared herself Pharaoh, she dressed in men’s clothing and was depicted in sculpture with masculine traits. Her text is about how her statue was created by the ‘Divine Potter’, and she sits, as though before an altar, ‘… Poised between what I was and what I shall be …’.

Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut, ca. 1749–1459 BCE (Met Museum)

Other statues of her show her in a more feminine aspect.

Seated Statue of Hatshepsut, ca. 1749–1459 BCE, Met Museum

Jake Heggie: Statuesque – No. 3. Hatshepsut: The Divine Potter (Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; Jake Heggie, piano)

Alberto Giacometti’s Standing Woman of 1948 returns us to the 20th century in a flash. Giacometti’s elongated statues, which seem to both make the body vanish while also making us aware of the individual that was behind the imagery – someone who is there and not there at the same time – were part of his unique style. Insubstantial and fragile while at the same time a definite person, the statue stands on a platform that is tilted towards the viewer, seeming to throw the statue forward. The musical text is a reflection on Giacometti’s effect ‘I do not see myself, | But who I am is there’ and the statue views itself in a long line of depictions of women in art, ‘He makes me feel that I am linked| To a distant, bygone age’.

Alberto Giacometti: Standing Woman, 1948 (MoMA)

Jake Heggie: Statuesque – No. 4. Alberto Giacometti: Standing Woman, 1948 (Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; Jake Heggie, piano)

The last sculpture dates to 190 BCE and was discovered, shattered into more than 100 pieces, on the island of Samothrace. One of the masterpieces of the Hellentistic era, the statue depicts the goddess Niké (Victory) alighting on a ship’s prow to celebrate their sea battle victory. The statue is exceptionally powerful but lacks a head, arms, and feet. Despite the archaeologists’ best efforts, these have never been unearthed. The song text has the goddess address the infinite number of visitors who stare at her every day, asking them not to look at her body but to imagine what she’s thinking or dreaming…. despite having no head. Her anger growing, by the end of the song she roughly dismisses them: ‘Well, I need someone who cares. | Not someone who obsessively stares. |It’s over. It’s done. We’re through! |Now get out’.

The Winged Victory of Samothrace, 190 BCE (Louvre Museum)

Jake Heggie: Statuesque – No. 5. Winged Victory: We’re Through (Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; Jake Heggie, piano)

Goddesses, queens, muses, and unknown models are all here – the variety of women in the world.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter