Stephen Hartke: The King of the Sun

American composer Stephen Hartke (b. 1952) was commissioned by Chamber Music America for a work for the Los Angeles Piano Quartet. Written in 1988, his piece The King of the Sun is based on paintings by the Spanish artist Joan Miró dating from 1928 to 1974.

Carl Van Vechten: Joan Miró, 1935 (Library of Congress)

Catalan-Spanish painter Joan Miró (1893–1983) started drawing at age 7 and had his first solo show in 1918 – it was not a success. His paintings were ridiculed and defaced. Leaving Spain for Paris, Miró went to the artists’ communities around Montparnasse. He moved to Paris in 1920 but continued to spend his summers in Catalonia. After the debacle of his first exhibition, Miró, starting in the circles of the Fauvists and Cubists in Paris, modernised his style and joined the Surrealists. Yet, his style was always individual and often was described as ‘dream-like’.

His painting language was symbolic and schematic, and by 1924, he had achieved a linear simplification that was unique to him.

Stephen Hartke, 2009 (Photo by Philip Channing)

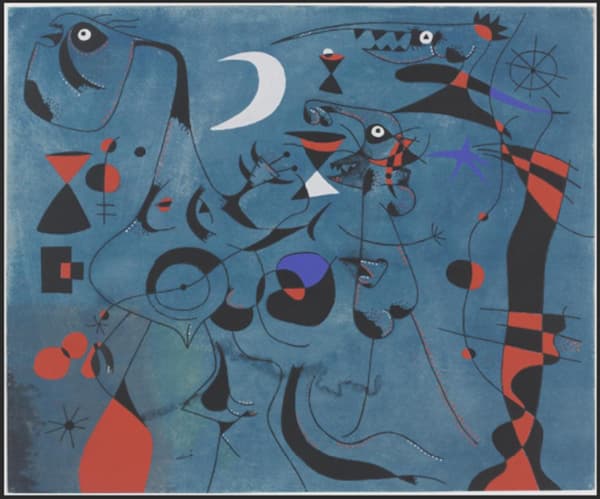

Hartke took his title, The King of the Sun, from a modern mistranslation of a late mediaeval work Le ray au solely (The Sun’s Ray). The first movement, Personages in the night guided by the phosphorescent tracks of snail comes from a 1959 portfolio of 22 drawings and a lithograph that accompanied Proses parallèles by André Breton. It was issued as the collection Constellations. The paintings ‘celebrate nocturnal themes of wonder, joy, nature, love, and escape’ and were created while Miró was exiled from Spain during the Spanish Civil War and later. He created them from January 1940 to September 1940, and they were smuggled to the US for their first exhibition in 1945. They were a tremendous influence in the US on the new abstract expressionist movement.

The third image in the Constellations collection was Personnages dans la nuit guidés par les traces phosphorescentes des escargots (People at Night, Guided by the Phosphorescent Tracks of Snails), painted in Varengeville on 12 February 1940. Set at night, as are so many of the Constellations works, the painting has sharp red and black designs with white and blue highlighting, set against a blue background.

Personnage dans la nuit guidés par les traces phosphorescentes des escargots (People at Night, Guided by the Phosphorescent Tracks of Snails), 1940 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

With a tempo marking of ‘Stealthily’, Hartke sets out on his Miró journey. It’s muted and is filled with silence, like the night. It starts and stops; it jumps and processes. Miró ‘personages’ are monster-like with their sharp teeth and glaring white eyes. In the middle, the moon casts its bright glow. The work ends with repeated footsteps leading away.

Stephen Hartke: The King of the Sun – I. Personages in the night guided by the phosphorescent tracks of snail: Stealthily (Los Angeles Piano Quartet)

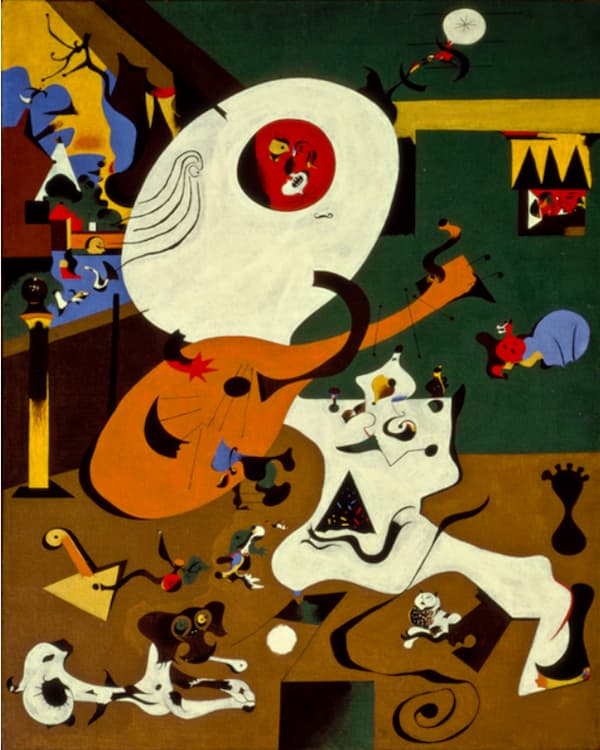

The second movement is based on a series of 3 paintings based on postcards of 17th-century Dutch genre scenes. The Intérieur hollandais (I) (D’après “Le joueur de luth” d’Hendrick Maertensz Sorgh) (Dutch Interior (I) (After Hendrick Maertensz Sorgh’s The Lute Player) takes the precision and naturalism of the originals and distorts them in dream-like fashion.

In Hendrick Martenszoon Sorgh’s The Lute Player, created in 1661 and held in the Rijksmuseum, a lute player performs for a distracted lady who is keeping her eyes on him, no matter where her thoughts may roam. They are seated before a table piled with fruit, his music book open before him, on an open veranda. There’s a dog on the bottom left, and a cat curled up under the table. On the wall behind, the picture of Pyramus and Thisbe suggests harmonious love…or is a warning against impulsive lust. Although the title is The Lute Player, he’s actually playing a theorbo with its extra bass strings.

Hendrick Martenszoon Sorgh: The Lute Player, 1661 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum)

Joan Miró’s rereading of the scene 267 years later preserves the lute, the dog, and a cat that looks more like a baby. The bowl of fruit is reduced to a single pear and the lady has seemingly vanished. Other understated elements of the original picture, such as the balustrade on the veranda, the vines over the window, and the houses outside, are overemphasised and given strong colours. The naturalism of Sorgh’s original has departed in a rush.

Joan Miró: Intérieur hollandais (I) (D’après “Le joueur de luth” d’Hendrick Maertensz Sorgh) (Dutch Interior (I)

(After Hendrick Maertensz Sorgh’s The Lute Player), 1928 (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

For Hartke, the second movement, Dutch interior, with its tempo designation of ‘Phantasmagorical’ is the key to the entirety of The King of the Sun. Written last, this movement is written as a violin solo, but a solo where the other, lower voices are completely unconnected with it, play an estampie that has a mediaeval form and has an isorhythmic structure. This canon also appears in the 4th movement.

Stephen Hartke: The King of the Sun – II. Dutch interior: Phantasmagorical (Los Angeles Piano Quartet)

The third movement is based on Miró’s 1945 work Dancer listening to the organ in a Gothic cathedral, we have the moon and stars, and a cross, but also strange heads with antennas and two different coloured eyes. Lines curl and curve around the figures and symbols.

Joan Miró: Dancer listening to the organ in a Gothic cathedral, 1945 (Fukuoko Art Museum)

Like granite, ‘granitic’ is the direction for the piano and that’s exactly how it opens: hard and rocklike. Despite the softer sounds of the strings, the hard piano returns again and again.

Stephen Hartke: The King of the Sun – III. Dancer listening to the organ in a Gothic cathedral: Granitic (Los Angeles Piano Quartet)

Here follows a brief interlude. Its stealthy steps could be part of any one of Miró’s night images.

Stephen Hartke: The King of the Sun – Interlude (Los Angeles Piano Quartet)

Movement 4 is based on Les flammes du soleil rendent hystérique la fleur du désert (The flames of the sun make the desert flower hysterical) and musically is based on the canon that first appeared in the second movement but compressed into bright and abrupt chords. This is the only movement based on an image depicting daylight and burning daylight.

Joan Miró: Les flammes du soleil rendent hystérique la fleur du desert, 1938

With a shiver of strings, the hysteria flowers react to the sun’s rays (ah, a reference to the title of the mediaeval text from which the piano quartet takes its name). The hapless flowers cannot evade the sun’s rays and so thrash about.

Stephen Hartke: The King of the Sun – IV. The flames of the sun make the desert flower hysterical: Fiery (Los Angeles Piano Quartet)

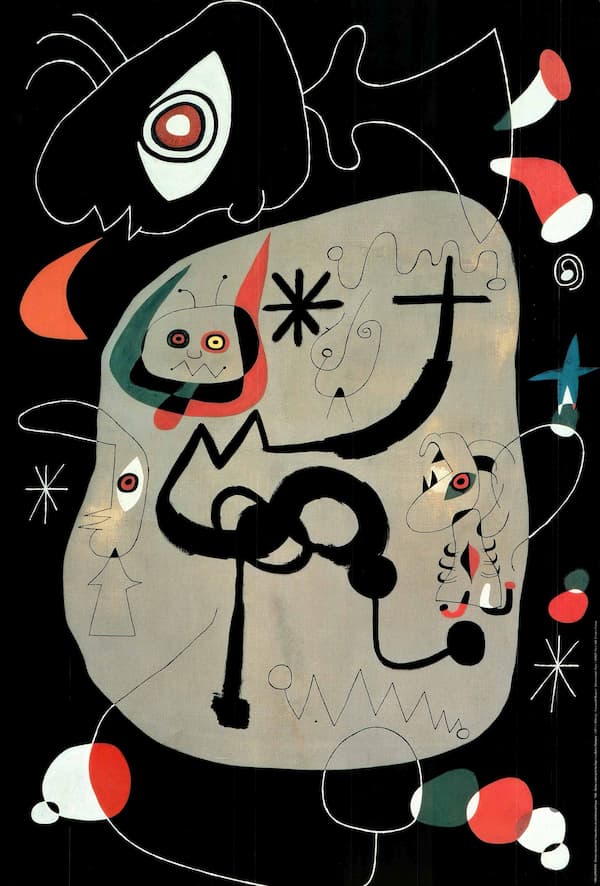

The final movement is Miró’s dark vision of birds reigning supreme above the disturbing images of cyclopes emerging out of the blackness of fire. Paint was thrown and splashed on the canvas, an idea taken from American artists. The birds in the air hold back the rising dark and fire.

Joan Miró: Personnages et oiseaux dans la nuit, 1974 (Paris: Centre Pompidou)

The last movement gives a lighter impression than does the fiery darkness of Miró’s work. In many ways, this final movement brings us back to many of the ideas from the other movements, such as the ‘snail music’ from the first movement (and other places). The composer’s tempo indication, ‘quietly energetic, with an air of innocence,’ perhaps puts us in the position of the birds, flying above the disturbances above.

Stephen Hartke: The King of the Sun – V. Personages and birds rejoicing at the arrival of night: Quietly energetic, with an air of innocence (Los Angeles Piano Quartet)

Hartke’s reading of Miró over nearly 50 years of paintings is an interesting interpretation of visual change. We may go back in time to the medieval estampie in movement II, but at the same time, we’re in the dissonance of the modern era.

As the composer notes, although the title is The King of the Sun, only one movement is set in daylight. All the rest are from Miró’s visions of night, with their attendance moons and stars. Things change at night from how we perceive them in daylight and Hartke’s quiet ending leaves us in Miró’s dark.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter