Inspirations Behind Maurice Delage’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon

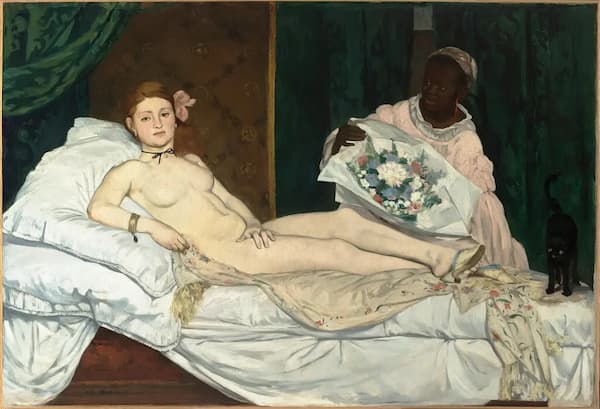

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) shocked the art world with his 1907 painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Some of its shock value may be realized by its original title: The Brothel of Avignon. Another part of the shock value was its size: 8′ x 7′ 8″ (243.9 x 233.7 cm).

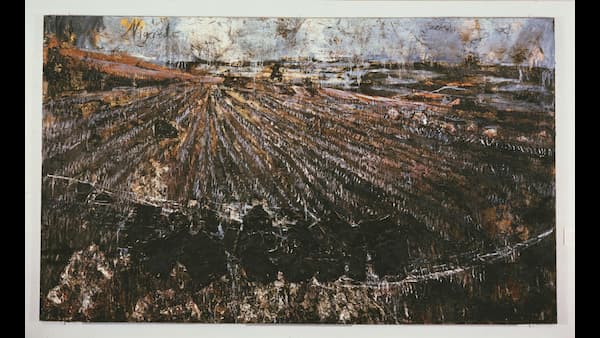

Harry B. Lachman: Pablo Ruiz Picasso, 1915

The five women pictured were 5 prostitutes in a brothel on the Carrer d’Avinyó (Avignon Street) in Barcelona, Spain. That this is an international gathering is read from left to right: a north African or south Asian woman, 2 Iberian women, and on the right, 2 women with African-mask features. They have covering wraps that have fallen off, and there’s a bowl of fruit, with apples, pears, grapes, and a melon. The women are nude, but their bodies are not given in detail.

Picasso: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907 (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

Picasso discarded whole swathes of Western art in this painting: the perspective is flat, and the women are drawn in a compressed plane, reduced to their basic volumes. They are not true portraits, and some elements, such as the fruit and the masks, point to the characteristics of Cubism that would be developed by Picasso and Georges Braque later in the year.

When the painting was first exhibited in 1916 at the Salon d’Antin, it was considered immoral; the poet André Salmon changed the name of the painting from Picasso’s title, Le Bordel d’Avignon, first to Le bordel philosophique and then to its less scandalous title of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. In the process, the idea that these women were from a brothel named Avignon and not from the French city of Avignon seems to have gotten lost in time. Picasso hated the final title and would have preferred the mixed language title of Las chicas de Avignon (The Girls of Avignon).

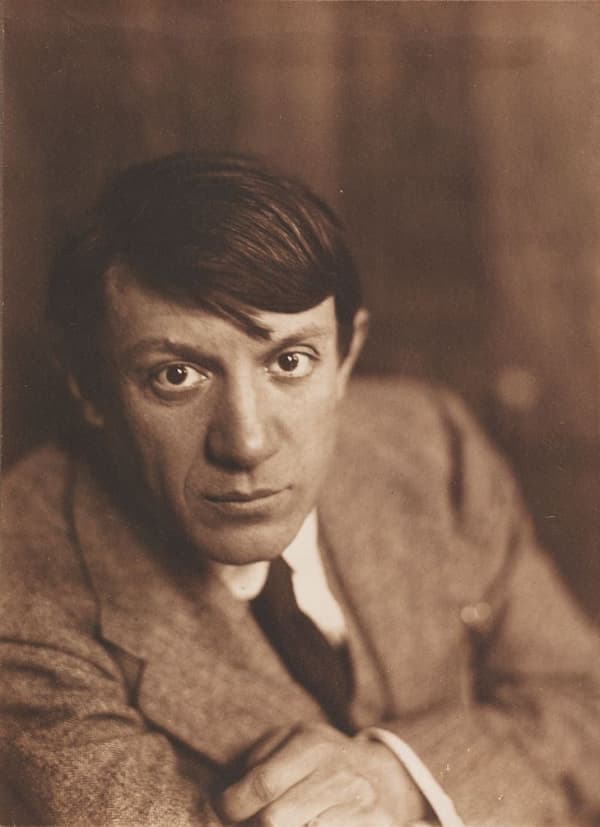

The French poet René Chalupt (1885–1957) created a poem of the same title, based on the painting.

Roger de la Fresnaye: Portrait de René Chalupt, 1921

In Chalupt’s poem, the women all decide to go bathing, where they are seen as ‘sweet prey’ to be caught by the brush of Picasso.

| Les demoiselles d´Avignon | The Young Ladies of Avignon |

|---|---|

| Les demoiselles d’Avignon | The young ladies of Avignon |

| Ont une rose à leur chignon | Have a rose in their chignon |

| Et des bas de soie à fines mailles | And fine-knit silk stockings |

| A leurs pieds mignons. | On their lovely feet. |

| Ont un ruban noir à leur cou | Have a black ribbon around their neck |

| D’où pend une croix d’or au bout | From which a gold cross emerges at the end |

| Et, tintant dans leur tirelire, | And, jingling in their piggy bank, |

| Une pièce de cinq sous. | A five-sou coin. |

| En revenant de Villeneuve | Returning from Villeneuve |

| Elles quittent leur robe neuve | They take off their new dresses |

| S’il leur plait de feindre l’ébat | If it pleases them to feign the frolic |

| Des naïades du fleuve, | Of the river naiads, |

| Offrant douce proie | Offering sweet prey |

| Au pinceau du peintre Pablo Picasso | To the brush of the painter Pablo Picasso |

| Qui s’est, pour les surprendre nues, | Who is, to surprise them naked, |

| Caché sous un arceau. | Hidden under an arch. |

Chalupt makes no comment on their differing appearance, nor the fact that some seem to be wearing masks. He interprets the blue in the middle of the painting as the blue of their bathing place and the brown framing as the arch that they have hidden under.

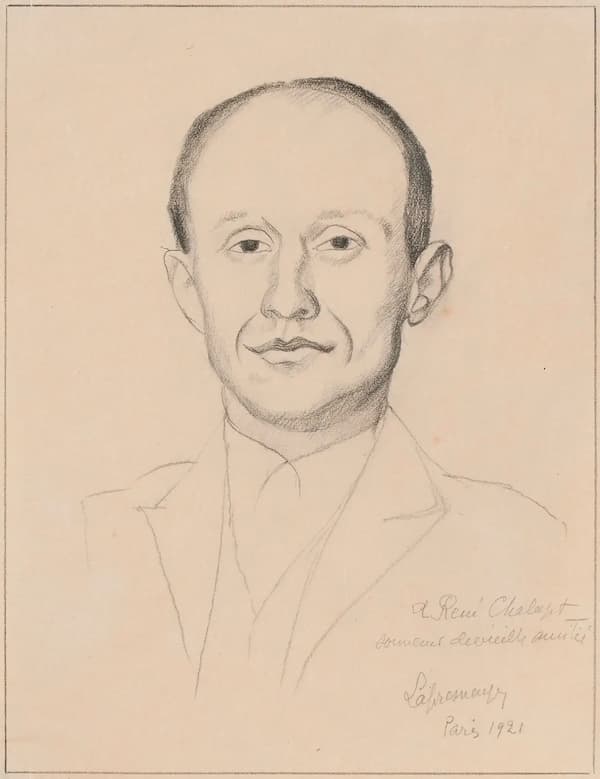

What’s interesting is that he’s imagining the women’s lives before Picasso painted them. He read the work as depicting French women who were originally dressed with roses in their hair, wearing silk stockings, and a black ribbon with a gold cross as necklaces. It’s an image that seems closer to Eduard Manet’s equally shocking 1863 painting of the prostitute Olympia, who does have a flower in her hair and a black ribbon necklace, but has already shed any stockings, silk or otherwise. ‘Venus has become a prostitute’ and in that line, we see how Manet’s woman is the modern woman. She’s not content to be viewed but returns the viewer with her own calculating look. As much as modern painting was founded on the concept of the idealised nude. Olympia takes back that idea with a modern twist.

Manet: Olympia, 1863 (Musée d’Orsay)

As in Manet’s Olympia, two of the demoiselles gaze at the viewer directly with eyes wide open and calm.

Maurice Delage (1879–1961) set the poem in 1924. He was a student of Ravel, who considered him one of the leading composers of the day.

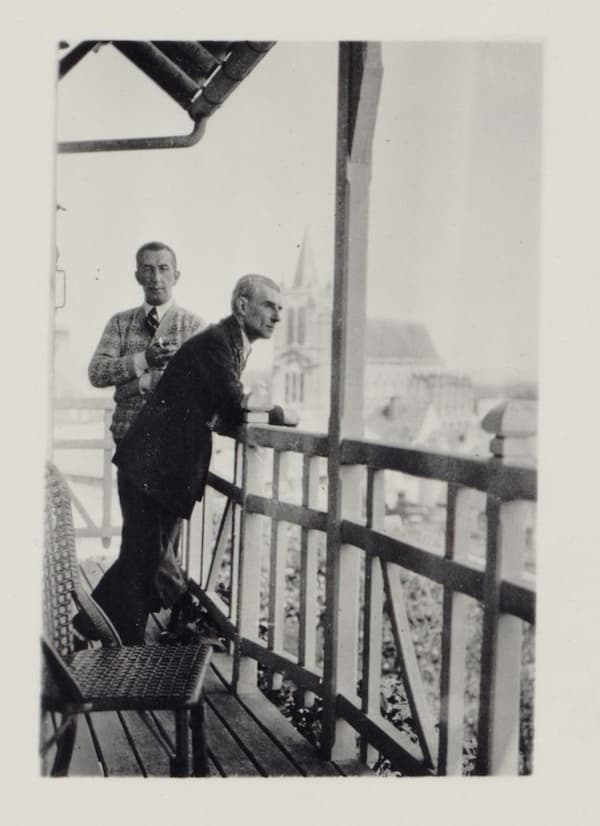

Maurice Ravel with Maurice Delage

He was a member of Les Apaches, a group of musicians, writers, and artists who formed around Maurice Ravel, the pianist Ricard Viñes, and the writer Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi. They started meeting around 1903, first in Paris and then at a property that Delage held.

In his setting of Chalupt’s poem, Delage sets a dancing melody and lusciously sets the description of their clothes. At the end, surprised at bathing by Picasso, they have little reaction, as the painting shows.

Maurice Delage: Les demoiselles d’Avignon (Elena Gragera, mezzo-soprano; Anton Cardo, piano)

From Picasso to Chalupt to Delage – each step gives us another dimension of the original painting.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter