William Alwyn: Derby Day

Commissioned by the BBC to replace a performance of his Second Piano Concerto, British composer William Alwyn wrote a lively overture that was only after the fact linked to a work of art. Alwyn agreed that the painting ‘seem aptly to describe the excitement and vitality of the piece’ and that painting was William Powell Frith’s Derby Day.

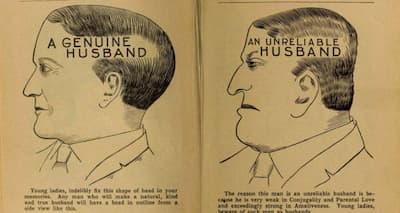

Derby Day, a sprawling 1 m x 2m canvas, was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1858 and was so popular that special systems had to be set up to keep back the crowds. It was the first of the great Victorian panoramas of English life. Frith was a believer in the ‘science’ of phrenology, where one’s character and social origins were visible in one’s face. These exaggerated images in a Louis Allen Vaught’s 1902 phrenology handbook Vaught’s Practical Character Reader show just how simplistic the phrenologist’s models could be.

Vaught on husbands, 1902

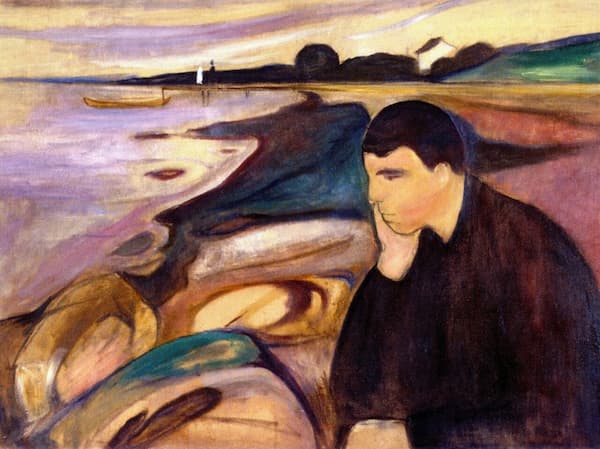

Each person in Frith’s image conforms to one of the phrenology stereotypes, particularly when depicting ‘people not like us’, i.e. criminals and their like. We no longer read this picture as those caught up in the ‘science’ could but we read other things in it – how people dress, the different classes from beggars to circus performers, to the middle class and the upper class and their actions. The idea of something being ‘high-brow’ or ‘low-brow’ came out of phrenology and it’s the concept we still use today.

Frith: Derby Day, 1856-58 (London: Tate Gallery)

To research this painting, commissioned by Jacob Bell, a chemist and amateur artist, Frith visited Epsom racecourse on Derby Day where he made drawings and sketches. Working for 15 months between 1856 and 1858, he used his sketches and hired models for the principal figures. In addition, he hired a photographer, Robert Howlett to take photographs from the top of a cab of as many strange groups of figures as he could. He used a real jockey for the model of the riders on the right of the picture and hired the acrobat and his son.

Looking closely at the picture, you’re rewarded when you focus on what the groups are doing. On the left, in front of the tent flying the flag of the Reform Club, a group of men in top hats is being tempted by a ‘thimble-rigger’, but it appears the only man tempted is the rustic in the white smock, who is reaching into his pocket as his concerned wife restrains him.

The thimble-rigger (detail)

In the center, an acrobat and his son are performing, but the son is looking away at the tempting picnic being laid out behind him. Here, we have the greatest mix of classes – high class in the carriage balanced by the working acrobats and the lower class begging woman with the baby.

The acrobats (detail)

In the carriages filled with race attendees, we have all levels of society, including a courtesan on the far right, who is being kept by the louche figure leaning on her carriage who seems to have an eye on the bare-foot flower seller. On the far left of the painting, balancing the courtesan’s fluff is a woman’s figure in a dark riding habit, one of the many high-class prostitutes who paraded through Hyde Park on horseback.

The flower seller (detail)

The use of phrenology models permitted Frith to show the perceived difference between a ‘decent working man’ and the man in trade who is ‘mimicking the middle class he aspires to join’. Viewers were fascinated by these kinds of paintings that permitted them to stare at people they would normally avoid the gaze of.

In his music to illustrate Derby Day, Alwyn starts with a busy, bustling scene that has its own quiet moments.

William Alwyn: Derby Day (London Symphony Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

Behind the scenes of this work is Alwyn’s own version of 12-tone technique which emphasized music that appealed to the heart rather than to the more mathematically inclined head. Even if the work took its name after the fact of composition, which even the composer agreed it was an apposite match, Alwyn has created a lovely work of modern excitement.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter