Max Klinger (1857-1920), Beethoven Statue, Secession, 1902

Klinger’s Beethoven statue, created for the 1902 exhibition in the Secession building in Vienna, shows Beethoven sitting in a concentrated, energetic pose on a richly decorated throne. He is portrayed as a bare-chested Olympic deity with Jupiter’s heraldic animal, the eagle, at his feet — human, but achieving godlike status through his music. For Klinger, music and sculpture as well as painting are related, even though they use different means of expression and production. For him, artistic creations emerge from the artist’s lived experiences and sentiments. Subsequently, paintings, poems and compositions are experienced by the viewer/reader/listener, who projects his own feelings and interpretations onto the works, which then become the viewer’s/reader’s/listener’s own ‘lived’ experience. For Klinger, it was less the ‘idea of music’ that inspired him, but specific works of Beethoven, Schumann, and Brahms — in particular Brahms’ ‘Fantasies Op. 116’ which Brahms had based on Hölderlin’s ‘Schicksalslied’ (‘Song of Fate’). Brahms himself was very interested in poetry and painting; he felt a deep affinity between the arts despite their different media and modes of reception. For him music itself was ‘sounding form in motion’ — reaching towards the infinite and depth of human subjectivity — hence his interest in the works of Anselm Feuerbach, Arnold Böcklin, Adolf von Menzel — and Max Klinger.

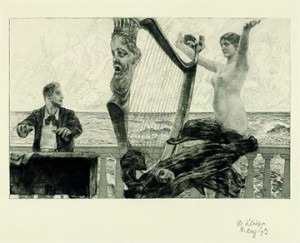

Max Klinger – Brahms Fantasy, 1894

In 1894 Klinger sent Brahms a printed copy of his graphic illustrations for the ‘Fantasies’ cycles with musical ‘opus’ numbers which had occupied him for many years. Klinger insisted that his graphic works did not ‘illustrate’ the music in the normal sense of the word, but that they provided musical interpretations of similar themes, again taking their imagery from Greek mythology, transmitting the spirit of the music. He also felt that he achieved the most dramatic range of both line and tone in his prints, etchings and engravings, since they left more to the imagination than would paintings. They encapsulated a sense, a form of indeterminacy which equaled the indeterminacy of Brahms’s music.

Max Klinger, Brahms Fantasy

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), Music, 1895

In future articles I will further explore this particular relationship between the arts, which will lead us to the Surrealist and Dada movements.