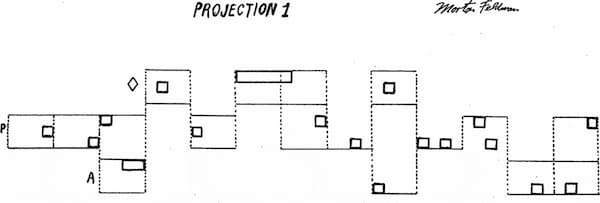

It was December 1950: composer Morton Feldman was doodling on a napkin, waiting for John Cage to finish cooking some wild rice. What Feldman had been drawing on this scrap of paper stuck with him and eventually became his landmark composition, Projection I for solo cello.

John Cage: Projection I

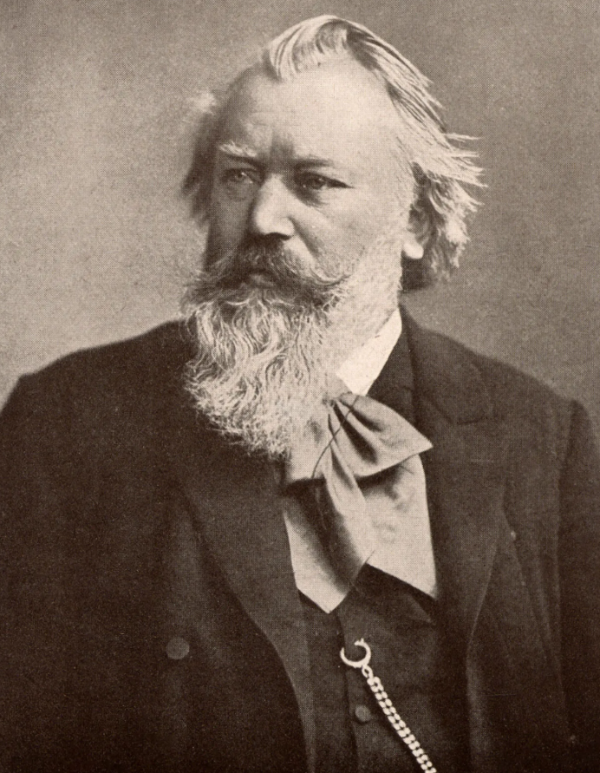

Over the subsequent two years, Feldman’s correspondent and colleague Earle Brown experimented with new forms of graphic notation, culminating in his Folio, 1952. In 1958, composers Christian Wolff and John Cage published their own experimentally notated works. These innovations in notation were sufficiently important and exciting that Karlheinz Stockhausen gave six lectures on the subject at the famous Darmstadt Summer Courses, as a series called “Music and Graphics.” These composers, and many others of their time, were open-minded radicals seeking to find groundbreaking ways of conceptualising and organising their music, performances, and interactions with instrumentalists and audiences. They sought to take accepted philosophical underpinnings of composing and interrogate them through discussion and experimentation. No longer was a score a standardised, hyper-accurate representation of what a piece should sound like according to the infallible and omniscient imagination of the composer.

Cut to 2024. A whole host of codified genres of visual notation are now widely accepted, at least within the community of people who are interested in “new music” and living composers. Christopher Fox notes that most new music is now notated in a way that falls into one of three categories: “more or less conventional scores, scores in which the visual domain is emphasised, and scores in which visual information is more or less replaced by verbal instructions.” Today, the possibilities seem as endless as one’s imagination and technology or materials – as long as you can find a performer who is willing, or even excited, to interpret your music. The positive implications of this are numerous and best, I believe, illustrated by taking a leisurely walk through some of my favourite graphic scores.

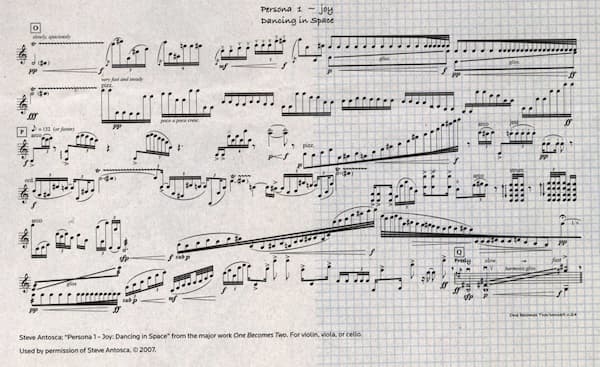

Steve Antosca: One Becomes Two

One unique quality of visually innovative scores is their capacity to affect – powerfully – the firsthand experience of the performer. One such example is Steve Antosca’s movement Dancing in Space from his One Becomes Two, where performers have clear visual “lines” and gestures but work mostly without any grounding “stave” and, therefore, without determinate pitches. For a score to feel untethered, whimsical, airy, and dancelike for a performer – all at once – is truly something special.

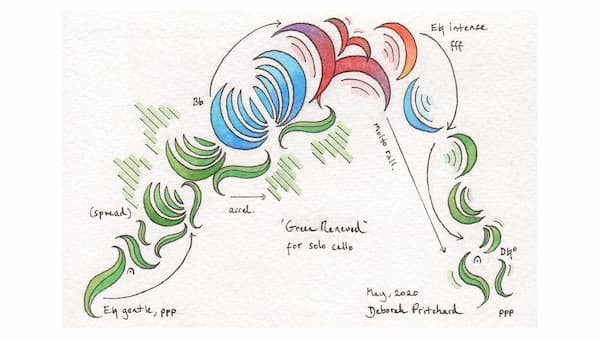

Deborah Pritchard: Green Renewed

This score by Deborah Pritchard exemplifies how graphic scoring opens up a whole new world of meaning for composers and performers for whom colour is particularly important or who may even have synesthesia. Indeed, graphic scores are often the most immediately communicative and accessible to all groups, as they don’t require the years of training in learning ledger lines and Italian terminology that traditional notation necessitates. Pritchard’s work constitutes an inherently multi-valent musico-visual artwork whose value lies both in its visual and musical qualities. Graphic scores allow for more interdisciplinary understanding between composers and visual artists and allow visually minded composers to use these skill sets in their creations.

Deborah Pritchard: Inside Colour (Jonathan Morton, violin; London Sinfonietta)

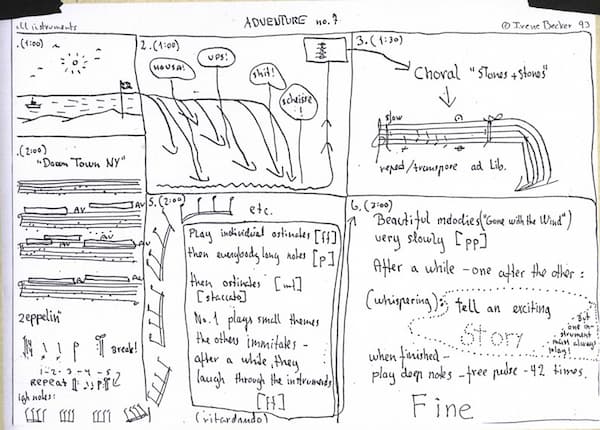

Irene Becker: Adventure no. 7

This composition by Irene Becker is aptly named – it is truly an “adventure” for those performing it, who are called to spend time together interpreting the score in a playful manner and making decisions together. Graphic scores like this open up the possibility for improvisation, bridging the gulf between improvisation and performance typically found in the world of classical or art music while also opening the door to indeterminacy and to each performance being totally unique. Traditional roles within the ensemble are also arguably broken down in favour of a more egalitarian, joint performance experience. Bruce L. Friedman’s O.P.T.I.O.N.S takes this even further, aiming to facilitate the most free improvisational experience possible within a group of players.

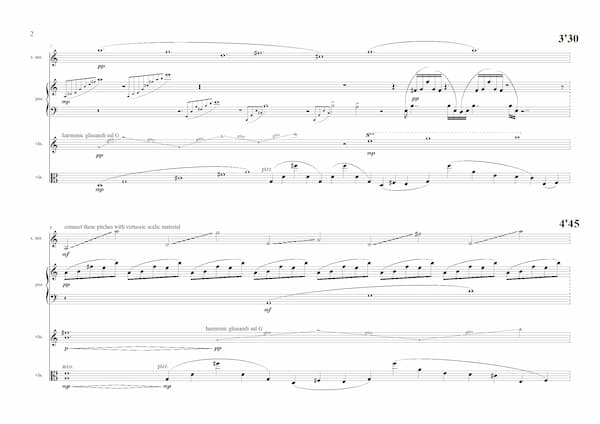

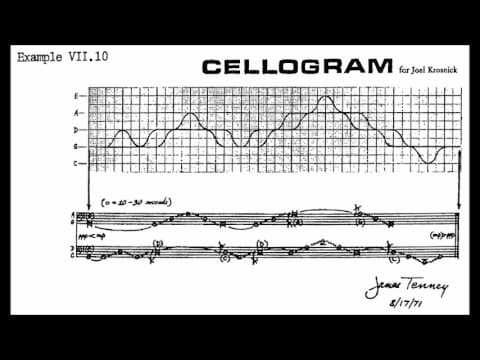

James Tenney: Cellogram

There are also many cases where the composer’s desired sonic outcome simply cannot be captured in its full nuances by means of traditional notation. In James Tenney’s Cellogram, Tenney has provided both graphic and traditional representations of what the cellist is to do – however, only the upper graph shows the smooth and precise moments of intersection and overlap in pitch glissandi, allowing the performer to fully realise the piece. Whether intentional or otherwise, graphic scores in their departure from ubiquitous notation software like Sibelius and Dorico constitute a kind of political pushback: against genericism, against the limits that notational software places on how we can write music, and even against the replaceability of human creativity by AI or automation.

Instead, whether through their literal handwriting or in the way we grasp how they think in their way of visually representing material, what comes through is a highly personal sense of the composer’s touch.

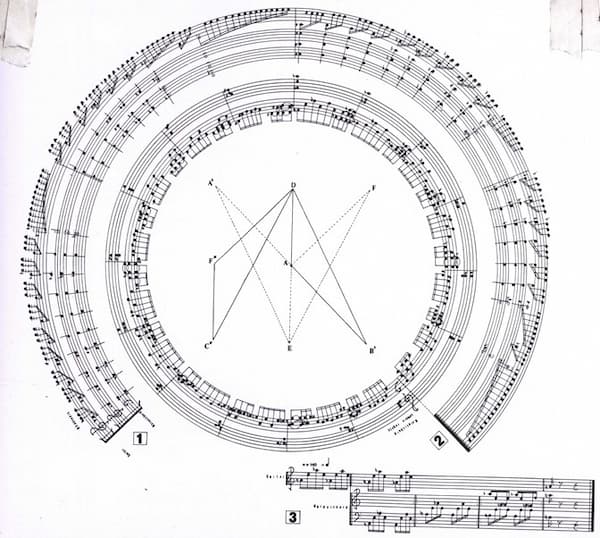

Joe Catalano: DreamFrame

This celestial piece by Joe Catalano shows us the possibility for musical scores to almost look (in atmosphere, effect, or vibe) the way they will sound while addressing or correlating with the overarching theme of the piece – in this case, the medieval idea of the “harmony of the spheres.” With this comes a deep, multi-layered coherence to the creation and experience of the work.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter